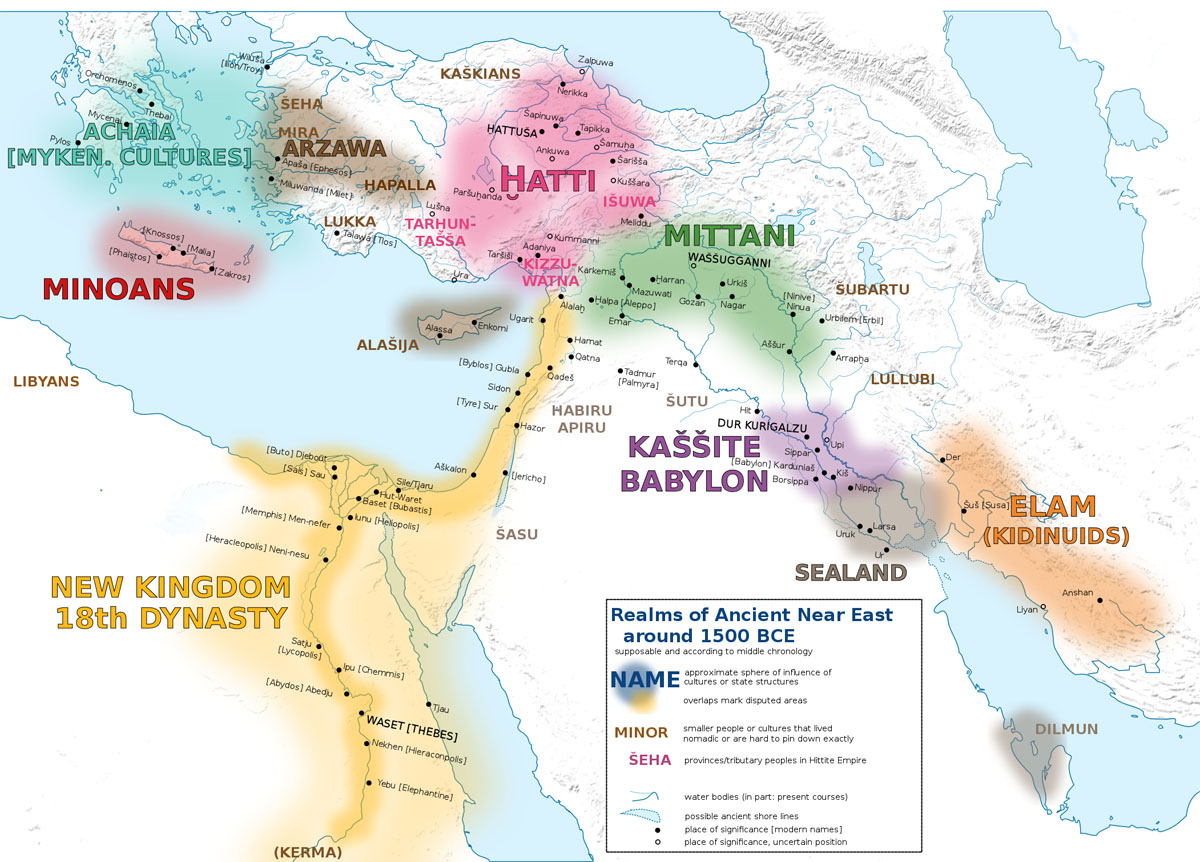

Basil (with okra in the background) — a negative entropy factory!

Edible order

I have written here before about negative entropy and its relation to life on earth. The post was “The opposite of entropy, and why we’re alive,” from December 2016. The concepts are based on a short but important book by the physicist Erwin Schrödinger, What Is Life. Yes, Erwin Schrödinger is the Schrödinger who gave us the thought experiment about Schrödinger’s cat. The book was first published in 1944 and has gone through at least eighteen printings from Cambridge University Press. I need to summarize some fundamentals, but this is a post about food, not physics.

The concept of entropy

The concept of entropy is simple enough, though a great deal of complex physics arises from the concept. It’s that systems always seek a state of equilibrium. This is laid out in the second law of thermodynamics, which explains why your cup of coffee gets cold. Your coffee will seek the same temperature as the room it’s in. As the coffee loses heat to the room, the temperature of the room will rise very slightly from the heat of the coffee. The thermodynamic system — the coffee and the room — seek a state of equilibrium. A state of equilibrium may sound all orderly and pretty, but the opposite is true. When a system is in a state of equilibrium, no work can be done. The engine in your car can do work only because high heat inside its cylinders (from burning gasoline) is much hotter than the surrounding environment. A gasoline engine would lose efficiency inside a hot oven and would eventually stop running as the oven got hotter.

Life

The physicist Roger Penrose extends Schrödinger’s ideas by pointing out that life on earth is possible because of the temperature difference between our very hot sun, which is surrounded by very cold space. A system that can take advantage of that differential (and the absence of temperature equilibrium) can do work. Penrose: “The green plants take advantage of this and use the low-entropy incoming energy [from the sun] to build up their substance, while emitting high-entropy energy [for example, body heat]. We take advantage of the low-entropy energy in the plants, to keep our own entropy down, as we eat plants, or as we eat animals that eat plants. By this means, life on Earth can survive and flourish.”

We can think of entropy as disorder, and negative entropy as order.

Life, then, to a physicist, is a system that can do work, and create order, by exploiting the temperature differential between a star and the cold space that surrounds the star. All life on earth is dependent on photosynthesis. All the work of photosynthesis must be done by green plants exposed to sunlight. Green plants are little factories that do the work of creating all sorts of orderly molecules that are essential to life as we know it. Animal life is possible because animals eat plants. Animals take in the order (or negative entropy) from the plants and excrete disorder. The taking-in and the excretion are equally essential.

Health and disease

First, a disclaimer. To think about health and disease in terms of entropy and negative entropy does not in any way deny, or conflict with, the sciences of nutrition and medicine. Rather, to think about our own life and health in the context of entropy and negative entropy is just a way of trying to keep in mind the most fundamental principles of what it is that keeps us alive and healthy. To be healthy, we want to maximize the order made possible by our hot sun and cooler planet. We can do that only by eating plants.

In my previous post on this subject, I asked a question as a kind of thought experiment: Would it be possible for human beings to live off of compost? I propose that the answer is no — at least, not for long. Though many of the minerals and even molecules necessary for life can be found in compost, the compost, by decomposing, has lost most of its order. Those minerals and molecules degrade into the soil and get recycled back through living plants exposed to the sun, creating order again by using energy from the sun. I would predict that, if we tried to live off of compost, we would sicken and die as the reserves of negative entropy in our bodies became exhausted and disorder set in. I also would predict that that disorder would be expressed as common, well-known ailments and diseases, leading to a common and well-known cause of death.

For example:

Origin of Cancer: An Information, Energy, and Matter Disease. (Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 2016.) “We therefore suggest that energy loss (e.g., through impaired mitochondria) or disturbance of information (e.g., through mutations or aneuploidy) or changes in the composition or distribution of matter (e.g., through micro-environmental changes or toxic agents) can irreversibly disturb molecular mechanisms, leading to increased local entropy of cellular functions and structures. In terms of physics, changes to these normally highly ordered reaction probabilities lead to a state that is irreversibly biologically imbalanced, but that is thermodynamically more stable. This primary change—independent of the initiator—now provokes and drives a complex interplay between the availability of energy, the composition, and distribution of matter and increasing information disturbance that is dependent upon reactions that try to overcome or stabilize this intracellular, irreversible disorder described by entropy. Because a return to the original ordered state is not possible for thermodynamic reasons, the cells either die or else they persist in a metastable state. In the latter case, they enter into a self-driven adaptive and evolutionary process that generates a progression of disordered cells and that results in a broad spectrum of progeny with different characteristics. Possibly, one day, one of these cells will show an autonomous and aggressive behavior—it will be a cancer cell.”

Increased temperature and entropy production in cancer: the role of anti-inflammatory drugs. (Inflammopharmacology, 2015.) “Some cancers have been shown to have a higher temperature than surrounding normal tissue. This higher temperature is due to heat generated internally in the cancer. The higher temperature of cancer (compared to surrounding tissue) enables a thermodynamic analysis to be carried out. Here I show that there is increased entropy production in cancer compared with surrounding tissue. This is termed excess entropy production. The excess entropy production is expressed in terms of heat flow from the cancer to surrounding tissue and enzymic reactions in the cancer and surrounding tissue. The excess entropy production in cancer drives it away from the stationary state that is characterised by minimum entropy production.”

The bottom line where our health is involved seems clear enough. Negative entropy and order lead to health. Entropy and disorder lead to disease. What we eat is extremely important for keeping order inside our bodies.

Concepts for better health

“Eat more leaves” is almost a mantra with the food writer Michael Pollan. He is, I think, not thinking about entropy or about physics from physicists such as Roger Penrose or Erwin Schrödinger. The science of nutrition tells us the same thing that physics tells us. Leaves, of course, are the primary source of the negative entropy that supports life on earth. Leaves are healthy things to eat.

Clearly freshness matters. A just-picked squash will turn into compost fairly quickly under certain conditions. Though a just-picked squash and a week-old squash will have identical amounts of some nutrients, clearly the just-picked squash will have more negative entropy, or order, because living things start to decompose as soon as they are cut off from their source of order. With a squash, that happens when you cut the stem between the squash and the leaves of the squash plant. The difference between a fresh squash and a composted squash is entropy. When you eat a squash, you absorb its order. What’s left is compost.

Eat as close to photosynthesis as possible. Chlorophyll itself is very good for us. Could we live on a diet of nothing but meat? Some animals do, obviously, though those animals evolved to be optimized for an all-meat diet (though they get vegetable matter from the entrails of the animals they eat). But human beings are not optimized for an all-meat diet. As Michael Pollan says, eat mostly plants.

Eat preserved foods only if fresh foods are not available. To live in the northern latitudes, it’s necessary to eat preserved foods. But why open a can of vegetables in the summer?

What animals eat matters. It seems reasonable to assume that milk or cheese from cows that ate grass would contain more negative entropy than milk or cheese from cows that ate moldy corn. Honey from bees fed sugar water couldn’t possibly be as good as honey from bees with access to fresh flowers.

Avoid processed foods. Not only do processed foods provide terrible nutrition with an excess of calories, the negative entropy has been processed out. Many processed foods are probably little better than compost, though they may taste better.

Cook sparingly and carefully. Cook with an eye to preserving the order contained in food. For example, be sparing with heat, using no more heat than is necessary to find the sweet spot between deliciousness, digestibility, and maximum order.

Lest this sound like quackery, I should point out that it only boils down to considering health from the perspective of fundamental physics rather than from the higher-level sciences of nutrition and medicine. Those sciences all lead to the same conclusions about what’s healthy and what’s not, though the physics emphasizes one point: Eat as close as possible to the order that plants create from sunlight. That’s another way of saying what nutritionists are saying when they encourage us to eat fresh, whole, unprocessed foods.

Why I have been thinking about this

Having our own garden, or living on a farm, obviously can be beneficial to our health. But even if we don’t have a garden, fresh foods are available in most places (to those who can afford it). I find it ironic that northern Stokes County, where I live, is considered a food desert because of the distance to places that sell fresh food. Many people here buy most of their groceries at places such as Dollar General, where absolutely nothing is fresh and everything is processed. The consequences to people’s health is obvious just from looking at the people in Dollar Generals.

I thought a great deal this spring, as I bucked myself up for a hot summer, about how my garden is my opportunity to maximize my intake, for a full season, of negative entropy from the summer sun. Or, to turn it into a jingle, make order while the sun shines. It’s in summer that negative entropy from the sun is freshest and cheapest. I strongly suspect that, just as we can store food for the winter, our bodies also can store negative entropy for the winter. So, as I see it, we have a kind of duty to take advantage of the sun in summer to benefit our health.

Stars

Stars and life have two interesting things in common. They are the only systems in the universe that can create order out of chaos. Stars actually can create negative entropy inside themselves for their own purposes.1 And stars also supply the radiant energy that makes life possible.

The astronomer Carl Sagan made the famous statement, “We are star stuff.” I would add to that statement: We are star stuff, powered by starlight.

Notes:

1. An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics, Second Edition. Bradley W. Carroll and Dale A. Ostlie. Cambridge University Press, 2017. Page 330.

Extra credit: One way of assessing the consequences of global warming would be estimating its effects on the ability of plant life on earth to create order from the sun. The health of oceans, forests, and tundra obviously is critical. It recently was reported that the Amazon is now a net producer of carbon, rather than a carbon sink. I don’t know of any data on how such things affect the planet’s net ability to create negative entropy. But it can’t be good. Yes, plants need carbon dioxide, as global warming deniers often point out. But carbon dioxide is not the only thing that plants need to flourish. They also need clean water, a suitable environment, and not being killed by human activities.