Julian the Apostate presiding at a conference of sectarians. Edward Armitage, 1875.

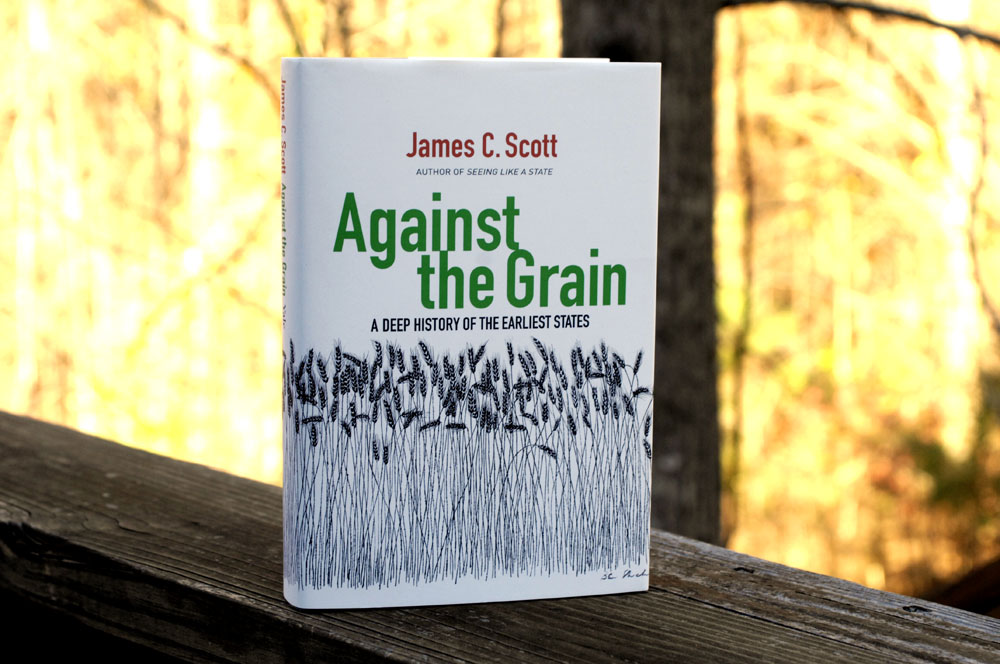

Julian, by Gore Vidal. Vintage International, 1962, 502 pages.

On the Gods and the Cosmos, by Sallustius, mid 4th Century.

Paganism’s last stand occurred in the 4th Century. Early in the 4th Century, the Roman emperor Constantine established Christianity as the state religion. A few decades later, the emperor Julian did his best to reverse it. Julian did not succeed.

I think it would be fair to say that the pagan intellectuals of that era did not see the conflict as a competition between the old gods and Christianity. Rather, they saw the conflict as a rational and living philosophy versus lifeless doctrine and dogma. These pagan Romans spoke Greek. Julian was trained as a philosopher at Athens. To them, Christian doctrine was (to put it bluntly) hickish and childish.

I have found it remarkably difficult to read up on the 4th Century. The 4th Century is covered in many general histories, of course, but I have been looking for sources that are limited to the 4th Century in particular. There are some new books by university presses, but they’re very expensive and narrowly focused (for example, on the city of Rome as an urban center). The old references — Gibbon, for example — are outdated. There are oodles of biographies of Constantine. But I’m not very interested in Constantine. After all, we now live in Constantine’s world. I couldn’t figure out what to read first, so I settled on Vidal’s novel.

Vidal is a good writer, in that, unlike so many people who write for a living these days, Vidal has an excellent command of the English language. But Vidal is not a good storyteller. He seems to lack a sense of drama. It’s as though he’s just dutifully writing up his research. That’s a shame. I can’t help but compare Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian, or Mary Renault’s Alexander novels. Yourcenar and Renault bring their subjects to life and make them human. Vidal is just not good enough as a novelist to do that.

Vidal, however, was a formidable intellect and a fearless heretic. I wonder if any other writers have ever really dared to write about the formation of Christianity as the cultural castastrophe it actually was in the eyes of philosophers such as Julian — the triviality of its texts; the depravity of its early bishops and theologians; its expropriation from the pagans of anything the Christians found useful; its lust for wealth, property and dominance; its habit of violence, persecution, and inquisition; its tendency toward quibbling and schism; its self-delusion about its absoluteness; the hypocrisy of its carnality vs. its other-worldly posturing; its imperial usefulness as a tool for subduing, pacifying, and, as necessary, exterminating the masses. “No evil ever entered the world quite so vividly or on such a vast scale as Christianity did,” says Vidal’s Priscus.

Gore Vidal died in 2012. I don’t think that we now have any public intellectuals who are quite like him or who can take Vidal’s place.

For a short, sweet read on how the last pagans saw the world, you probably can’t do better than Sallustius’ On the Gods and the Cosmos. Sallustius was a trusted friend and military leader in Julian’s army. What stands out in Sallustius’ writing is his sophisticated use of reason. He understands perfectly well that the pagan gods were myths and that the meaning of the myths had to be teased out with the tools of philosophy. Reading Sallustius, one becomes aware of how reason was smothered for centuries by Christian doctrine and didn’t get its head above water again until the Enlightenment. In many ways, it seems to me, this 4th Century conflict is playing out yet again.