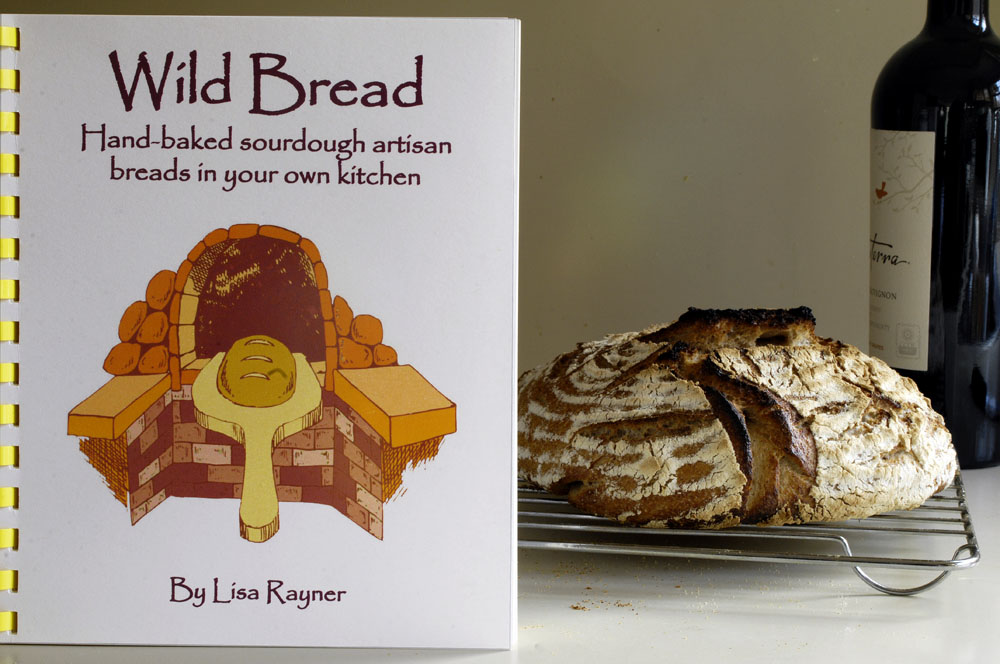

Up until recently, my philosophy on sourdough bread was influenced chiefly by Peter Reinhart (The Bread Baker’s Apprentice) and Michael Pollan (Cooked). While looking at reviews of cookbooks on Amazon, I came across this book by Lisa Rayner, Wild Bread: Handbaked Sourdough Artisan Breads in Your Own Kitchen. The book has definitely changed my philosophy of sourdough.

Technically, the main difference in Rayner’s approach is that she uses more starter. She builds up her starter with three successive feedings before mixing her dough. The starter provides nearly half of the total weight of the loaf.

But there is another difference in her philosophy of bread that is more subtle but very important. Pollan and Reinhart are city folk. Their references for bread are the sophisticated professional bakers that you find in the San Francisco Bay Area and New York. Whereas Rayner is much more rustic, more provincial, in her approach to bread. Provincial is good.

When good cooks ask me what my chief influences as a cook are, I name three: traditional Southern cooking as practiced by my mother’s mother, whose kitchen was supplied by a good-size farm; my eighteen years in California and my love for California cuisine as exemplified by Alice Waters; and hippy cuisine.

What’s hippy cuisine? Remember The Tassajara Bread Book? It was originally published in 1970. All through the 1970s, hippies were developing a new, healthier, more vegetarian cuisine. Think of Moosewood Cookbook (1977), or The Findhorn Family Cookbook (1976). In my opinion, these three very different approaches to cooking fuse very well. Wild Bread was published in 2009, but there is something very 1970s hippy-esque about it.

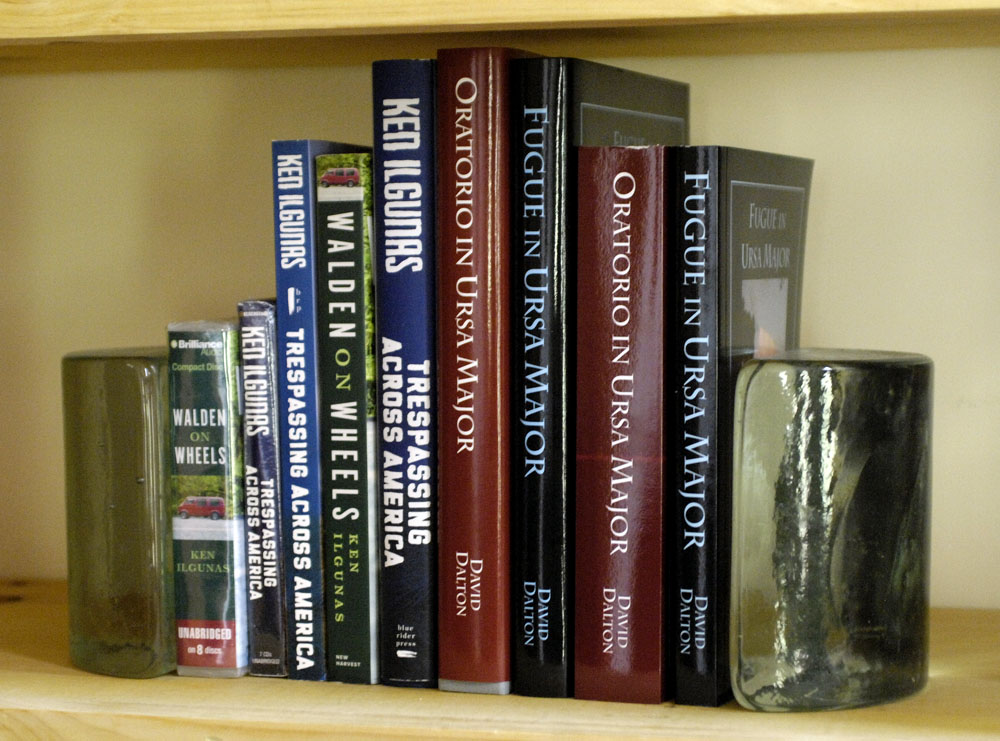

The first loaf of bread I made after reading Rayner’s method was just what I aim for — inherently and un-obviously sophisticated yet extremely countrified and rustic. As I said to Ken, the bread that Frodo and Bilbo ate in the shire was probably like that. In my imagination, at least, it’s what a loaf of bread might have been like a thousand years ago. Bread with that ancient quality just cannot be done with yeast. Only sourdough will do it. And, paradoxically, such a rustic bread can be achieved only with some hard-to-learn techniques and things that many kitchens don’t have — a baker’s peel, a baking stone, durum flour for dusting, and so on. One of those tools, unfortunately, is a steam oven.