November apples at Century Farm Orchards

Fatalities in the orchard during the last year include fig trees killed (above ground, at least) by brutally cold weather last winter, and another pear tree lost to the Black Death. Ken also found room for a couple more apple trees. Today I picked up some replacement trees.

I know I’ve harped on this theme before, but happy is the household with an established orchard. Rearing young apple trees is like rearing children in the Dark Ages — lots of them die, plagued with all sorts of pests, hazards, and diseases. The abbey’s orchard is six years old now, and it’s coming along. There was almost no apple yield this year, though, because last winter all the trees got a major pruning. This was probably the most important pruning of the trees’ lives, because it will pretty much determine the shape of the adult apple trees. Pruners say you should prune so that a bird can fly through the tree. That doesn’t leave a lot of buds for producing fruit the following season. But, during the 2015 season, with luck, the abbey should get its first serious apple harvest. That will be the orchard’s seventh year.

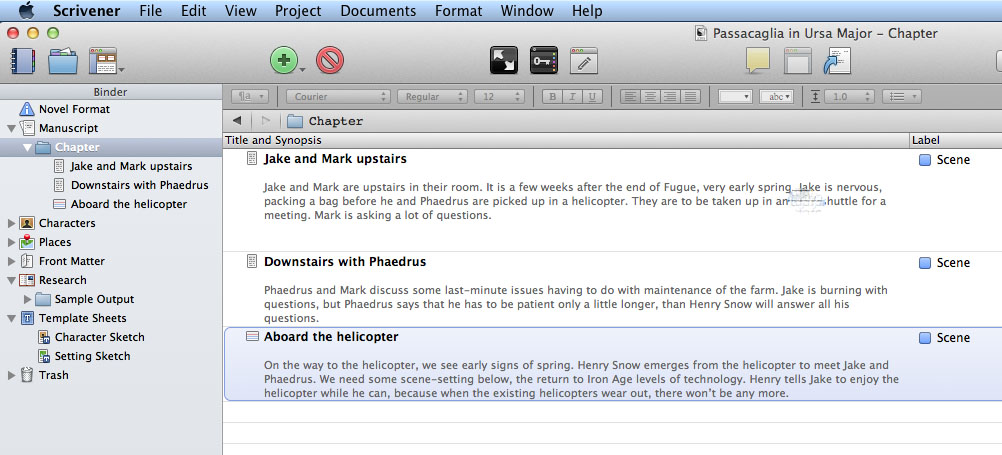

One thing I got right: Avoiding low-quality trees from mass-production nurseries, the kind of trees that are sold at box-store garden departments. I had bought a few such trees as replacements, and they just didn’t do well. Almost all the abbey’s trees came from Century Farm Orchards in Caswell County, North Carolina. They specialize in old Southern varieties of apple trees. These trees are very hardy and well-suited to the local climate, though like all young fruit trees they need a lot of care and attention to reach adulthood. Century Farm Orchards is not really a storefront operation. One orders trees early in the year. You get an invoice in October, and you pick up the trees at open house events in November.

Today’s new trees included two mammoth blacktwig apple trees, two kieffer pear trees, a brown turkey fig, and a celeste fig.

Another nice thing about the abbey’s modest-size orchard is that it’s on a fenced slope, nicely turfed, fed on organic fertilizer and lots of chicken droppings. The grass and clover in the orchard are incredibly lush, and of course all that organic nutrition and earthworm activity works down into the soil and benefits the apple trees. We use only natural pesticides. The poor trees pretty much have to fend for themselves, like 9th Century peasant children.