I think Lily is telling me that “Luca” is not as good as reviewers said it is.

Watching a bewildering world from the middle of nowhere

I think Lily is telling me that “Luca” is not as good as reviewers said it is.

People in these parts are still flying their Trump flags. Many are faded and tattered. This one has fallen and has been down for days.

The Republican Party, as it is currently constituted, and, given the course it’s on, cannot win another national election. The 2020 election made that clear. And yet, with the exception of a very few Republicans such as Liz Cheney who retain the ability to work with facts and reason, the Republican Party has chosen to double down on its losing politics. That begs a question: What’s the real goal? Do they actually believe that they can revive Trumpism into a winning politics? Or is there some other goal?

A Reuters-Ipsos poll in May found that 53 percent of Republicans believe that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump. For Americans as a whole, the number is 25 percent. Both numbers have dropped slightly since last November. What could possibly reverse that trend, given the indictments against Trump operatives that are in the works, the public hearings that Congress will hold, and the trials and guilty pleas of those who stormed the U.S. Capitol on January 6? I fully expect that Trump will be indicted, too — the greatest perp walk in American history.

It does make sense that Republicans would have a competition to be the next Trump — people such as the governors of Florida and Texas, and some people who will soon be indicted, such as Matt Gaetz. But what’s in it for them other than some publicity and getting a piece of the Trump grift pie? There is no way to win an election with a politics that only 25 percent of the population will buy. And not only that, but Trumpists also don’t seem to realize that, every time they talk to the cameras, every time they pull off a move such as requiring a state’s students and faculty to state their political views (which just happened in Florida), they horrify reasonable Americans and drive their support even lower.

So what do they really want? We can only guess, or try to connect the dots, keeping in mind that different players may have different motivations. The most benign guess I can make would reflect the position of players such as Mitch McConnell, senator from Kentucky. What he wants, I think, is to use every erg of power he can muster to block progress and to protect a status quo which redistributes income (and power) up. Greater equality is the last thing that Mitch McConnell wants. Others, I’m afraid — and the Trumpier they are the truer it is — want to maximize turmoil, rage, division and disinformation, because that kind of environment best serves their purpose. There are many who believe (including some on the far left) that nothing can be changed without tearing everything down first. That Trumpian purpose aligns with the purposes of the non-NATO world, which wants a weaker America. They have been meddling, too, though it’s difficult to sort out foreign meddling from homegrown sabotage.

The media, unfortunately, benefit from turmoil and division. The more we are afraid that Trump or Trumpism is going to return to power and that Trump is going to get away with everything, the more the media benefit. And yet, we cannot turn our backs. The very best single source I know of for following ongoing events is Heather Cox Richardson’s daily posts on Facebook. She is a historian.

Some of my liberal friends seem to be even more afraid of Trump and Trumpism now than they were when Trump was in power. They seem to be concerned that I’ve had a Panglossian failure of my faculties because I don’t think that doom is inevitable. We always knew that Trump would smash as much furniture as possible on his way out. But Trump lost. He cost the Republican Party the White House and the Senate. The power of the state is no longer at Trump’s disposal. Trump can no longer use the power of government to (like Russia) harass the opposition and obstruct justice to cover up the crimes of the powerful. Neither Trump nor his style of politics has anywhere near the support it would take to return to power. The more noise they make, the more they lose.

The Republican Party is still very dangerous, to be sure. For decades, Republicans have had to lie to win elections. Lies are no longer enough. Now they also have to cheat. Republicans still have strongholds in the states, and they are hard at work to try to leverage that for every advantage possible, including trying to legalize cheating.

Thinking about today’s politics always seems to bring me back around to the question of character. What kind of people would lie and cheat to win elections, push rage, like crack, to the point that people actually would invade the Capitol with violent intent, and poison the American democracy to keep the rich rich (and untaxed) and the people they hate down? That kind of people can’t be reformed or reasoned with. They can only be contained. My view is that, not only is their power now contained at the national level, the law and norms that contain them are closing in, in the form of justice. A cracked-up, fact-free, completely unprincipled minority cannot seize or hold power without committing crimes. Seeing their leaders in prison should do a lot toward showing the Trumpian hordes that they’d best go home and rethink their lives.

I had the good sense this year to plant a sparse garden for easier maintenance. Even so, when the garden kicks in, you can’t turn your back on it even for a day. I had skipped a day of harvesting, and this morning I picked five pounds of squash and cucumbers from four squash plants and four cucumber plants. Some of the squash and cucumbers had already gotten a little too big.

Unlike tomatoes, which love to sit and look out the kitchen window, squash and cucumbers start to lose their freshness the instant they’re picked. I pick them in the cool of the morning, wash them in cold water, dry them, and pop them in the fridge.

I’d have fried fresh squash every day in summer if it weren’t for the calories. Curried squash is probably the lowest-calorie way to fix them. When I fry squash, I like to not use egg. I slice the squash and let the slices sit for about 10 minutes. A sticky dew will form. That stickiness helps the flour stick. Roll the slices in seasoned flour. Then roll them in a mixture of flour, seasonings, and water, about the same thickness as you would with an egg mixture. Then roll them in semolina flour and pop them in the skillet.

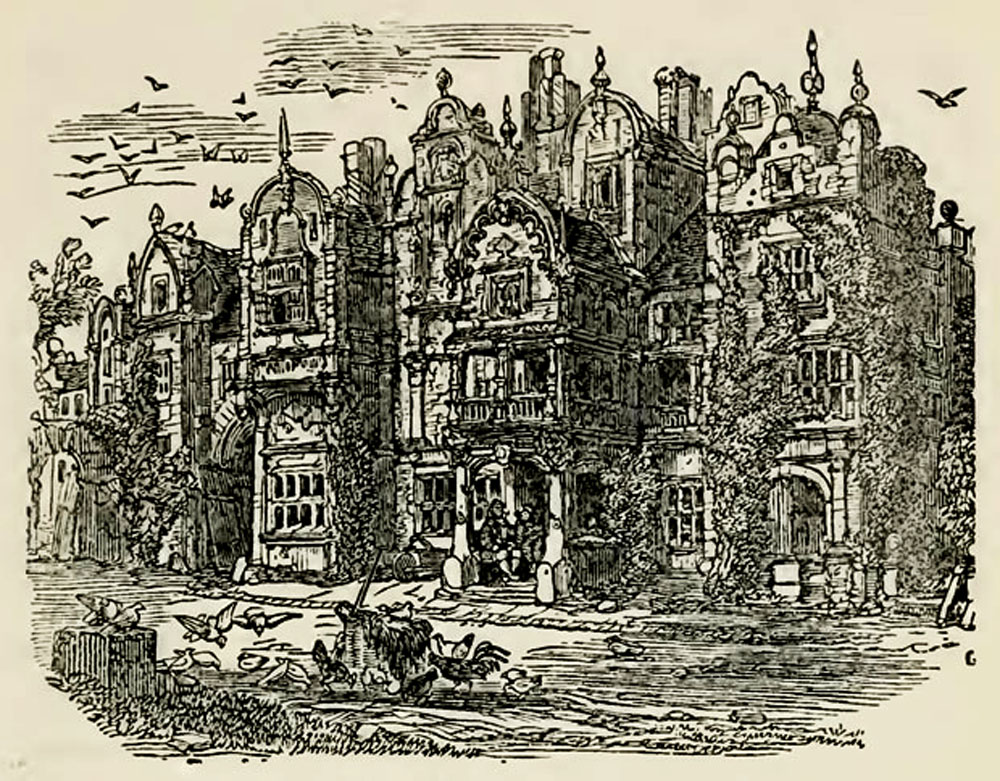

The Maypole Inn

Choosing the next novel to read is a huge pain in the neck. I Google for novels on particular subjects or particular periods, or I pore over book lists, and then I look up the books on Amazon. Sometimes I settle on a novel that looks like it might be a good choice, but when I “look inside” the Kindle edition on Amazon, I quickly see that the author cannot write. I move on.

When stuck between novels, reading a classic is a fallback that rarely fails. I have a Kindle file with the complete works of Dickens. I settled on Barnaby Rudge. I am no stranger to Dickens. I have read David Copperfield at least twice.

Yes, Dickens’ style is a little thick. His characters, especially the wicked ones, usually border on caricature. Important scenes are usually melodramatic. And yet few novelists have ever been able to paint pictures in the mind the way Dickens does. His style, actually, is remarkably cinematic. According to the Wikipedia article on Dickens, in 1944 Sergei Eisenstein wrote an essay on Dickens’ influence on cinema. Dickens may have invented the technique of cross-cutting, in which the narrative shifts back and forth between things that are happening at the same time.

There is a particular reason for reading Barnaby Rudge at present. The novel is about the Gordon Riots of 1780. The similarities between the Gordon Riots of 1780 and the Trumpist insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, are remarkable, so remarkable that I’m surprised not to have come across an article about it. Some things never change, including the sickening religious character and mob-affinity of people who do such things. Lord George Gordon was an odious man, the puritanical head of the Protestant Association, horrified by the idea of Catholics having equal rights. Yep. The mob attacked Parliament.

Even if you are reluctant to take on such a long book (almost 700 pages) and such a dense read, the opening scenes of Barnaby Rudge are worth reading. It is a dark and stormy night, and the story opens inside a country inn ten miles outside of London. Few writers can conjure atmosphere the way Dickens can. Dickens’ Maypole Inn very much reminds me of Tolkien’s Prancing Pony. What could be more cozy and comfortable that an inn in old England (or Scotland, or Ireland) on a dark and stormy night? Another thing about Dickens that I love: When people are eating, he always tells us what.

I don’t really find Dickens’ style of writing archaic. So many novelists, especially today, just can’t write. There is still much to be learned from Dickens about how it’s done.

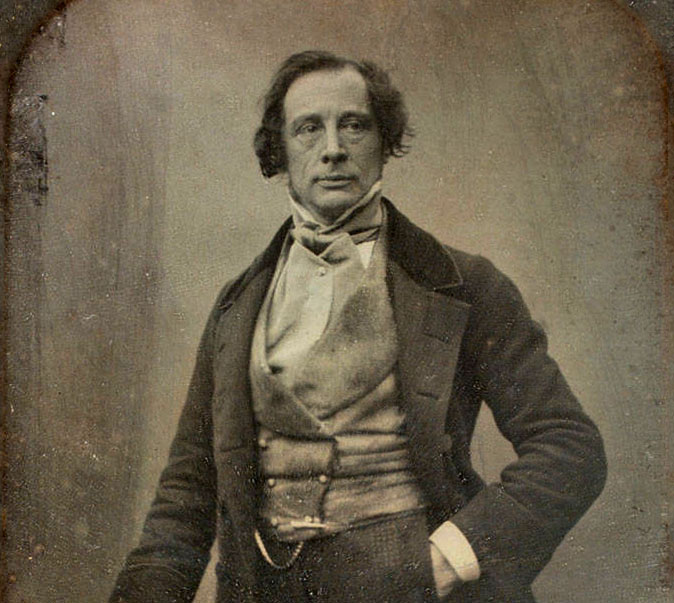

Charles Dickens in 1852. Source: Wikipedia

Homemade tagliatelle with basil-parsley pesto. The basil, parsley, and lettuce came from my garden. The pesto was made with a mortar and pestle.

When I posted last week about working on my Italian cooking (“A summer project: Italian cooking,” June 2), I was not thinking about pasta — honest. I was thinking about how to make the most of the summer vegetables from my garden.

But as I read more and more of Elizabeth David’s Italian Food, I realized that pasta is part of the deal in Italian cuisine. So I needed a pasta plan — including figuring out how not to eat too much of it.

It was easy to see that a pasta machine would be necessary. I am pretty sure that I will never, ever, be able to make pasta with a rolling pin. So, when I was grocery shopping on Tuesday, I stopped by the Williams Sonoma in Winston-Salem and bought an Imperia (made in Italy!) pasta machine, $80. This is a hand-cranked machine. Williams Sonoma also has attachments for KitchenAid mixers. But the attachments are much more expensive than the hand-cranked machine, and I reasoned that a pasta machine driven by such a high-powered motor would be a very high-powered way to make a very big mess.

With the hand-cranked machine, at least, the mess is much less than I feared. I was afraid of a sticky mess. But instead it was a mere floury mess. If you’re used to handling dough, your second batch of pasta will be excellent. I won’t presume to give any instructions here, because I’m just a novice. But there are many videos on YouTube about how to make pasta at home.

Amazon also has the Imperia machine, for less, naturally, than I paid at Williams Sonoma. It’s a heavy little thing. And it’s entirely practical, not at all a use-it-once kitchen gadget.

I do have one warning. Most recipes for pasta will make an outrageous amount of pasta, enough to feed a family of ten, to require a 40-gallon cauldron for boiling, to keep you turning a crank for half a day, and to run out of places to hang pasta. If you’re cooking for an old-fashioned Catholic family, I understand. But since I cook only for myself and for the possum who makes nightly visits to my backyard, even a one-egg batch of pasta is more than twice as much as I can eat. My possum will eat Italian tonight.

A thought that helped me overcome my resistance to making something as high-calorie as pasta is that pasta skills (and a pasta machine) also will assist with egg dumplings, which would make a fine winter comfort food. Also, the method of making Asian noodles can’t be that different from making Italian pasta.

I’m probably the last California-influenced cook to start making pasta. There are two skills involved, I would say: How to make the pasta (easy); and how not to make too much of it (hard). The real technical challenge with homemade pasta, I would say, is making no more of it than you ought to eat.

Click here for high-resolution version. The photo was shot with an iPhone 12 Max Pro.

The day lilies are about a week late this year, because of the cool spring. I have some day lilies in the front ditch by the road, but most of my day lilies are on a bank above the driveway. I call it the day lily bank. Twelve years ago, a few weeks after the bank had been graded and was nothing but exposed soil, I planted 300 day lily sets. Now those 300 have multiplied into thousands. The bank is dense with day lilies.

Unfortunately, the deer like the day lilies as much as I do. For the past two years, they’ve eaten the buds and blooms as fast as they would grow. So far this year, the deer seem to have forgotten the day lilies. Or maybe they have something better to eat. Just before I took this photo, I saw a hummingbird visiting the day lilies.

The day lily buds and blooms (as the deer well know) are edible. If the deer will leave some for me, some of the buds will find their way into salads and pestos. Unfortunately, day lily season is short. And each bloom lasts only one day.

The new hoe

I confess that I ruined my old hoe. I left it out in the weather too often. That weakened the handle, and the handle separated from the blade. The blade fell off while I was hoeing a row of tomatoes. To wear out a hoe would be an honorable thing. But to neglect and abuse a hoe is a crime and a shame that would have shocked our ancestors.

I know better than to leave garden tools outdoors, but I plead guilty to doing it. Wooden handles deteriorate. Blades rust. As I reflected on my cruelty and guilt, hoping that my contrition will ensure that I never harm another hoe, I realized how ancient the hoe must be. The hoe is a kinder blade than the sword and the ax, but no doubt it changed the world just as much.

The Wikipedia article on the hoe describes some of the history. Hoes are mentioned in the Code of Hammurabi, about 1750 B.C. Even today, Third World subsistence farmers with no ploughs get by only with hoes. When there is no iron or steel, wood will do. The Wikipedia article includes a photo of an Egyptian hoe made of wood. The Roman hoes, of course, were made of iron.

In European culture, there can be no doubt that hoes were introduced across Europe in the migrations that brought agriculture, the wheel, the horse, milk animals, and the Indo-European languages. How could I be so thoughtless as to leave out in the rain an instrument so royal? I vow to never treat a hoe with disrespect again. I should be able to salvage the old hoe and put a new handle on it, though replacing handles on hand tools is becoming a lost art.

My new hoe has a fiberglass handle. That was the only kind of hoe the hardware store had. I’ve made a hook in the shed for it to hang from, away from the rain and sun. Fiberglass won’t decay like wood, but it hates ultraviolet from the sun.

One of my favorite gardening books, Gardening When It Counts, emphasizes the importance of keeping hoes sharp. I find that to be true. I use a hoe in the garden not so much for loosening the soil but for cutting weeds. It’s remarkable, really, how efficient hoes are for that. As long as the weeds don’t get out of hand, I can hoe my garden in not much more than 30 minutes.

The new hoe (and probably all new hoes) came with an angle on the blade, but the blade is not truly sharp. I took a file to it. I’ve also ordered a sharpening tool from Amazon that attaches to a drill. The rotary sharpener is made for lawn mower blades, but I’m pretty sure that it will do a good job of sharpening the hoe.

When I was a young’un growing up in the Yadkin Valley of North Carolina, I wasn’t made to work as much as some young’uns were. But I was sometimes made to hoe. I didn’t like it. But I’m glad to have acquired some hoeing skills early in life. And since this post is an obituary for my old hoe, I want to mention that my old hoe never harmed a living thing that wasn’t a weed, not even a snake. Many a hoe, like pitchforks, have been used as weapons.

When I lived in San Francisco, I learned that people who grew up without any farm experience did not even understand the expression “a long row to hoe.” That is sad. I have looked down long, long rows of weedy tobacco on hot summer days.

Rest in peace, old hoe. If I can find a new handle for you, I’ll bring you back and never mistreat you again.

A friend who lives in the south of France asked me yesterday in email what plans I have for summer. I couldn’t think of a thing, other than trying not to hide too much indoors in a bug-free, air-conditioned house. Then I remembered one thing: That, with the riches I hope to get from the garden, I plan to work on my Italian cooking.

It was about ten days ago, upon observing that though the early garden was 90 percent a failure because of the cold, dry spring, the summer garden looks promising. I will have yellow squash next week. The cucumbers and tomatoes are blooming. The basil and onions are coming along, but slowly. I planted okra from seed today.

Like most Americans, I grew up with spaghetti. Every few years or so I’ve made lasagna at home. I put some effort into improving my pizza skills, especially with crusts. I’ve had a few incredibly good dinners at proper and properly Italian restaurants in North Beach in San Francisco. But I have never made an effort to concentrate on authentic Italian cooking. I realized that I needed a book for that.

Cookbooks are available from Italian cooks with current TV shows, but I wanted something classic. The classic work on Italian cooking for English-speaking cooks was easy to identify. It’s Italian Food, by Elizabeth David. It’s one of the most beautiful cookbooks I’ve ever seen, illustrated with excellent color prints of Italian paintings of food. The book was printed in Verona.

Italian Food. Elizabeth David. Barry & Jenkins, London, 1954, 1987, 1996. 240 pages.

First published in 1954, this book satisfies my curiosity about what any culture’s cuisine was like when the cooks had experience and memories that went back to the 1800’s. What I saw in my grandmother’s kitchen in the Yadkin Valley of North Carolina in 1954 (she was born in 1896) was nothing like what one sees in even the best kitchens today. New developments in cuisine, such as the ideas of an Alice Waters or a Michael Pollan, are very important. But cooking also has roots, and some knowledge of those roots is a must-have for any cuisine.

I ordered this cookbook through Amazon. It was shipped from the United Kingdom. There must be a good many copies in print, because the book is not hard to find. Booksellers don’t usually say what edition they’re selling. Mine is the 1996 edition, in very good condition.

I’ve a lot of good reading ahead of me, but the part about basil convinced me that this is indeed the cookbook I want:

“Nothing can replace the lovely flavour of this herb. If I had to choose just one plant from the whole herb garden I should be content with basil. Norman Douglas, who had a great fondness for this herb, would never allow his cook to chop the leaves or even to cut them with scissors; they had to be gently torn up, he said, or the flavour would be spoilt. I never agreed with him on this point, for the pounding of basil seems, on the contrary, to bring out its flavour.”

By pounding, I assume she means pounding in a mortar and pestle, which is now the only method I will use for making pesto.

Italian cooks, she writes in 1954, go to market twice a day. That’s a beautiful idea, but no American can live that way anymore. Some of us can, however, go to the garden twice a day.

Elizabeth David, who died in 1992, is an important figure in the history of cooking and cookbooks. The Wikipedia article is a good starting place for information about her.

Click here for high-resolution version

Lettuce pesto with lettuce from my garden

Lettuce pesto sounds bland and watery. In truth, it is a little bland and a touch watery. But if lettuce is what you’ve got, then lettuce pesto it is. It will be three weeks or so before I can expect any summer basil from the garden. The winter basil from the kitchen window is almost gone, but I had enough of it to season the lettuce a bit.

As I have said here before, few sounds on earth can equal the sound of well trained, well directed human voices singing together. There is the sound of the sea crashing against rocks, and birds in a garden on a spring morning, or children laughing and a cat purring. But, somehow, life on earth also learned to produce sounds like this.

The theology is dreadful, so it’s best to leave the German below as German. I was unable to find a decent YouTube performance that included the instruments scored below. This piece, like so many, is much more often murdered than performed well.

In the best of all possible worlds, there’d be no need for insecticides. But permethrin, at least, seems to be pretty benign. Permethrin is a synthesized version of pyrethrin, an organic insecticide made from chrysanthemums. The most scary thing about permethrin is how persistent it is. Clothing treated with permethrin can remain effective against insects (and ticks) through up to six washings. Still, it’s not very toxic to humans, especially after it has dried.

Each year, the tick situation seems to get worse. When I was a kid, I knew of only one kind of tick, the kind of tick that dogs got. But now there are several varieties, and I can’t distinguish one from another. I do know, though, that these days we have very small ticks, especially in the spring and early summer. They’re harder to detect because they’re so small, and their bites are just as offensive as larger ticks.

I have found that treating clothing with permethrin is very effective against ticks. It actually kills ticks — slowly, but quick enough to keep them from biting. On most summer days, two levels of defense are needed — permethrin for things that crawl, and Deet for things that fly.

The Center for Disease Control recommends the use of both permethrin and Deet. Also, here’s a nice article from NPR on permethrin. According to the article, it was the U.S. military that developed the method of treating clothing with permethrin.

Permethrin in liquid form is said to be toxic to cats. It’s best to treat clothing outdoors on a clothesline and leave things hanging until the permethrin dries. Don’t forget to treat your shoes and socks.