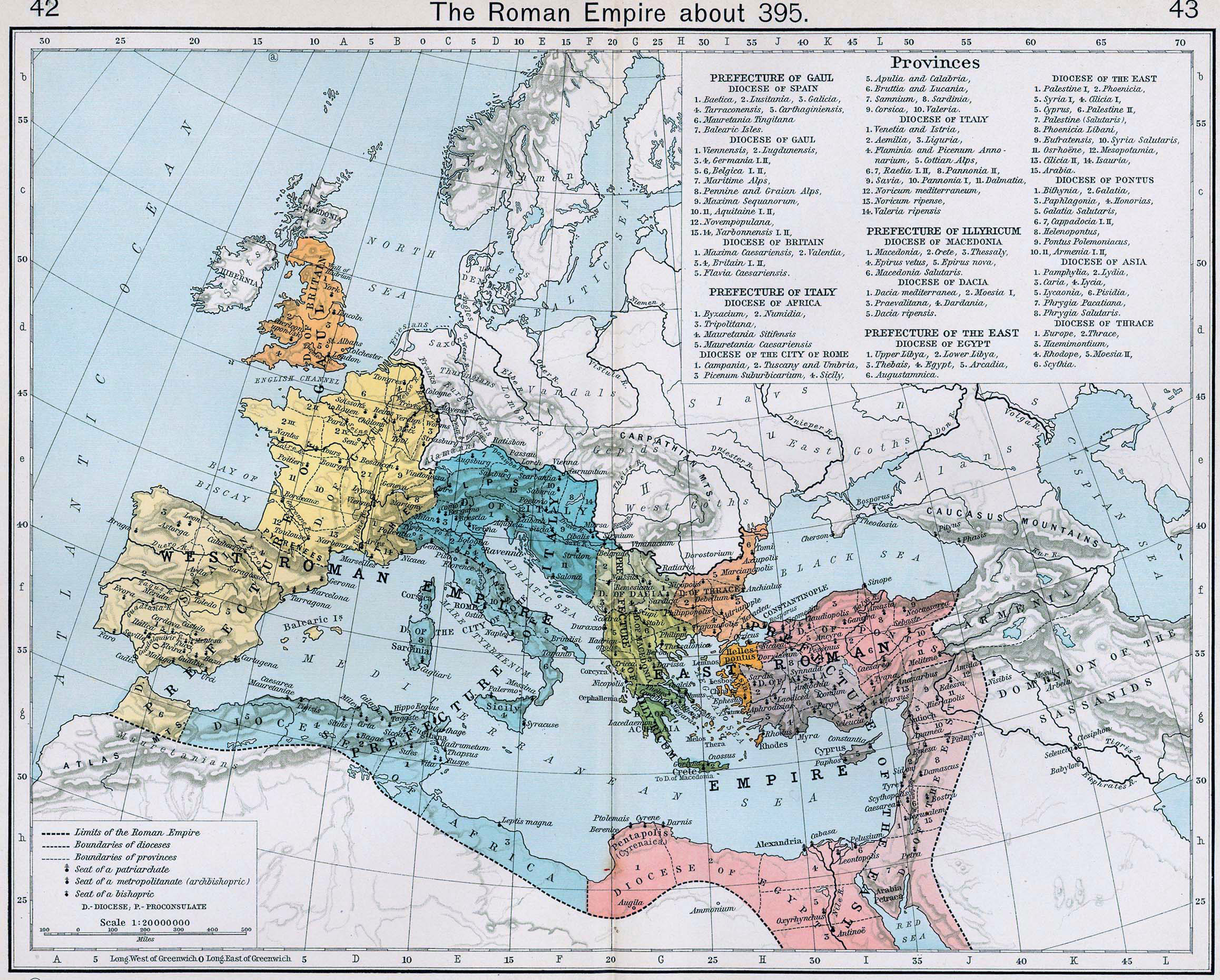

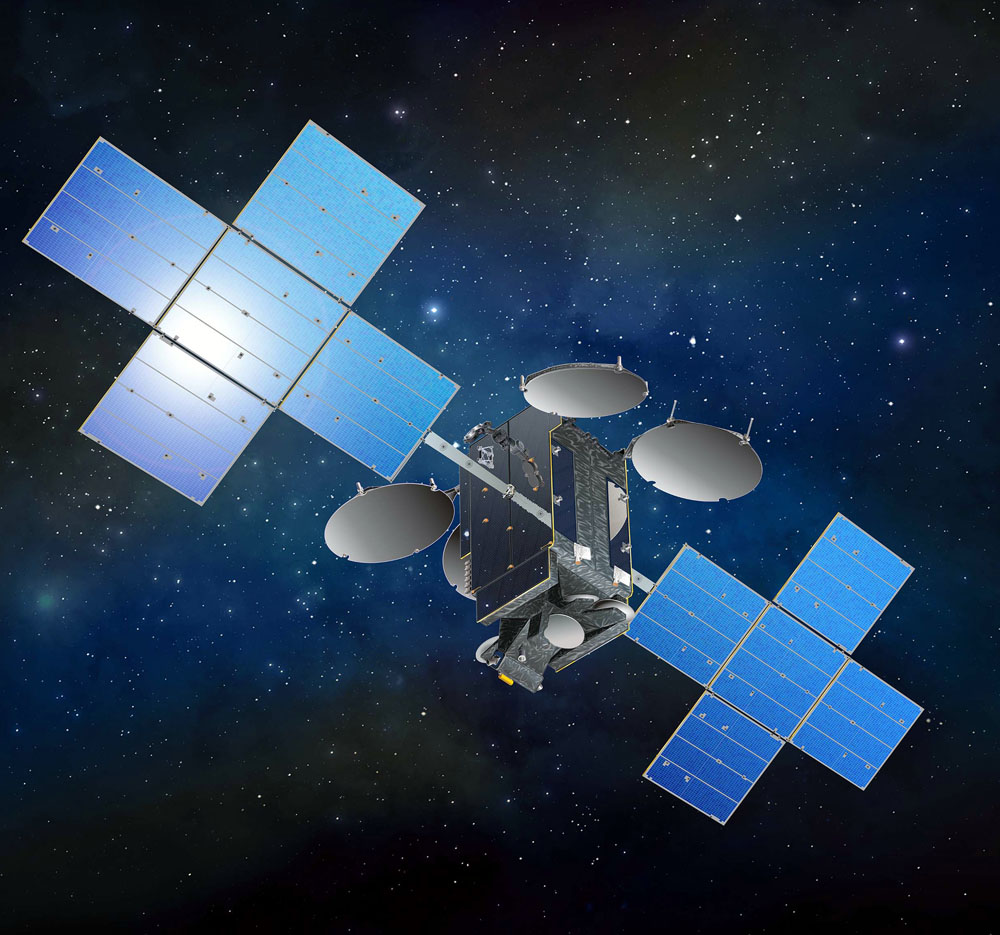

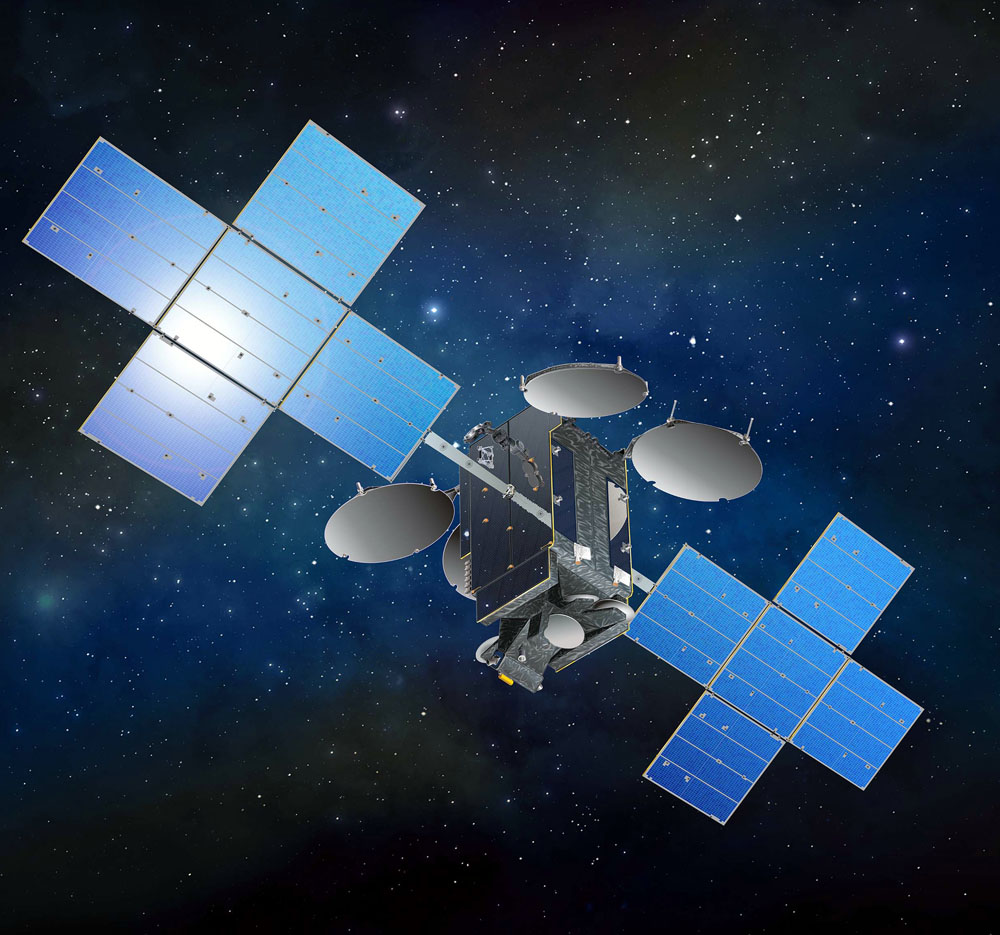

Dec. 18, 2016: HughesNet’s EchoStar 19 satellite aboard an Atlas 5 rocket, Cape Canaveral, Florida

HughesNet Generation 5 satellite Internet service ★★★★★

After eight years of living in a crippled and slow Internet hell, for the past six months the abbey’s Internet has been the fastest I’ve ever used. I owe it all to rockets and satellites.

This place is half a mile off the pavement, deep in the woods of the Blue Ridge foothills. If I weren’t a nerd, getting connected to the Internet these past eight years might even have been impossible. It required a directional antenna in the attic, connected to a Verizon “air card.” It was finicky and unreliable. Constant fiddling was required to keep it working, drawing on my experience both as a ham radio operator and lots of network savvy from my years as a newspaper systems person. All the Verizon components were lightweight consumer junk, because junk is all that is available for use with cellular. All cellular is consumer junk, but that’s a rant for another day.

As a nerd, it wasn’t enough just to understand the new dish in the yard and the new satellite transceiver and WIFI router down in the hallway closet. I also wanted to know what I was connected to up in the sky.

On Dec. 18, 2016, HughesNet launched a new satellite called EchoStar 19. It’s an SSL 1300 satellite, built by Space Systems Loral in Palo Alto, California — my old stomping grounds just south of San Francisco. It was carried to geosynchronous orbit by an Atlas 5 rocket launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida. The new satellite went into service in March 2016. I signed up in April.

Previously I had avoided satellite. The word-of-mouth reputation of HughesNet’s previous generations of satellite Internet service was not good. Though the EchoStar 19 satellite was new and un-reviewed, the specifications (true broadband by the FCC’s definition, 25Mbps minimum) and the deal that HughesNet was offering were irresistible. I called and signed up. The very next day, a technician installed the dish. It has worked flawlessly from the beginning and has never let me down.

HughesNet promises typical speeds greater than 25 Mbps. I found that speeds of 45 Mbps were typical (and still are typical even as HughesNet adds customers). At times I’ve measured 53 Mbps. Upload speeds are relatively slow — 3 to 5 Mbps.

If you live near civilization and have the option of cable Internet, or, better yet, fiber Internet, you don’t need to consider satellite. A land-based service will be cheaper and fast enough. Only those who live in the boonies should consider satellite service. The three drawbacks of satellite Internet service are:

1. It will be more expensive

2. Your data allowance will be capped each month

3. The distance to the satellite (23,000 miles) forces a delay, or “latency,” of about half a second when you’re waiting for a response, simply because of the speed of light and the 46,000-mile round trip to the satellite.

I chose HughesNet’s 30GB per month plan. I also signed up for telephone service (which is a problem; more in a second) and for the higher-priority service plan if I needed a technician on site. For this I pay $131 a month. I don’t begrudge a penny of it.

The deal from HughesNet is remarkably generous. In addition to the 30GB per month, you also get 50GB per month of off-hours data between 2 a.m. and 8 a.m. If you exhaust the 30GB (more in a second), they don’t cut you off. Instead, they throttle the download speed to 1.5Mbps or so for the rest of the month. Your Internet service actually is unlimited. But your fast Internet service is limited according to the data plan you choose. You can buy more fast data by paying for a “token” ($15 will get you 15 more fast gigabytes), but otherwise you are throttled and in “FAP” mode, in which FAP stands for “fair access policy.” This makes sense. A satellite’s bandwidth is not unlimited, and HughesNet must be able to provide fast data as promised to other users who have not exceeded their limits. Data hogs mustn’t be allowed to mess things up for everyone else.

Normally during the past six months, I’ve used less than 1GB a day, and at the end of the month I have unused data. But, this month, two teen-age great-nephews were among my Thanksgiving guests. In one evening, they exhausted my remaining gigabytes and threw me into throttled FAP mode with five days to go before my data reset. This was the first time I’d ever seriously been in FAP mode. The five days gave me plenty of time to see what throttled satellite service feels like.

It didn’t really feel any different! Not only do web pages load (subjectively) just as fast, I found that I could still stream HBO, Netflix, Hulu, PBS, etc., as though nothing had ever happened. This feels like a miracle to me and makes me want to buy some HughesNet stock. If I were, say, downloading a Mac OS update of 5GB, then that download would take 20 times longer when throttled. But for ordinary web browsing and movie streaming, throttling doesn’t much matter. At your throttled speed of 1.5Mbps, the system is loafing, and the download speed is very steady. So streaming services such as Netflix adjust to the available bandwidth, and the video never stalls. (Note: My streaming tests at 1080 px, high definition, are limited. I usually stream at 740 px, which looks perfectly fine on my 37-inch television.)

If you’re throttled in FAP mode, then at 2 a.m., when your off-hours 50GB bonus applies, the speed goes back up to the maximum. At 8 a.m., you’re throttled again. I have never used all the 50GB of off-hours data or even come close. This all strikes me as a very generous and rational pricing plan on HughesNet’s part. Why not let customers have extra data at night when demand is low? And why not let customers go on streaming at throttled speeds as long as the satellite can meet its promises to other customers? Would Verizon ever be that nice and that rational? Hell no. Us hates Verizon.

Telephone service

Telephone service has been a problem right from the start — dropped audio, dropped calls, and lots of aggravation. HughesNet acknowledged the problems and made some fixes. Nevertheless, though the telephone service has improved some as they’ve worked on the system, I still would rate the telephone-over-satellite service as just short of acceptable. You’d want this only if you have no other options. Increasingly I am resolved to just stop using the telephone, because in these days of cell phones the horrible audio is just too much to bear. Emailing and texting suit me much better. I almost never answer the telephone anymore. But that’s a rant for another time.

Tech support

There are two ways to get tech support. You can make a phone call, talk with someone in India, and have an aggravating and utterly unproductive experience. (I had to do this a couple of times because of telephone problems). But HughesNet also has an on-line support forum. A very nice moderator named Liz will open tickets for you and actually get things done. Longtime, highly technical HughesNet users in the forum also can be very helpful.

The router, etc.

The HT2000 satellite transceiver and router provided by HughesNet has worked flawlessly for six months. It will enable two WIFI networks, one at 5Ghz and one at 2Ghz. The 5Ghz network is faster but has less range and less ability to penetrate walls. This is a nice way to set things up. The WIFI networks are highly configurable, through your web browser. You also can test your satellite connection and get lots of diagnostics, should you need it (I never have needed it, but I watch things just out of nerdly curiosity). This stuff is built more to commercial, as opposed to consumer, standards. Cellular stuff is junk. Satellite stuff is cool.

The installation

The installation of the dish and router went smoothly, and, six months later, the satellite signal strength as reported by the HT2000 router actually has become stronger. I’d suggest tipping the installer generously before the work begins. They are independent contractors.

Bad weather

If there is a thunderstorm between your dish and the satellite in the southern sky, then your signal strength will weaken, and you may lose service altogether until the storm passes if the storm is a severe one. This is unavoidable with satellite. I’ve learned that, if the Internet stops working because there’s a thunderstorm to the south, I can expect heavy rain within the next 10 minutes.

Overall

I’d have to say that this is an excellent service, rationally priced. And the technology is beautiful.

An SSL 1300 satellite like HughesNet’s EchoStar 19