One of my favorite Mark Twain quotes is: “The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter. ’Tis the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning.”

What might he have said about the wrong word? I’d say that the wrong word is something like a train wreck. It screeches, lights the page on fire, and everything comes to a stop.

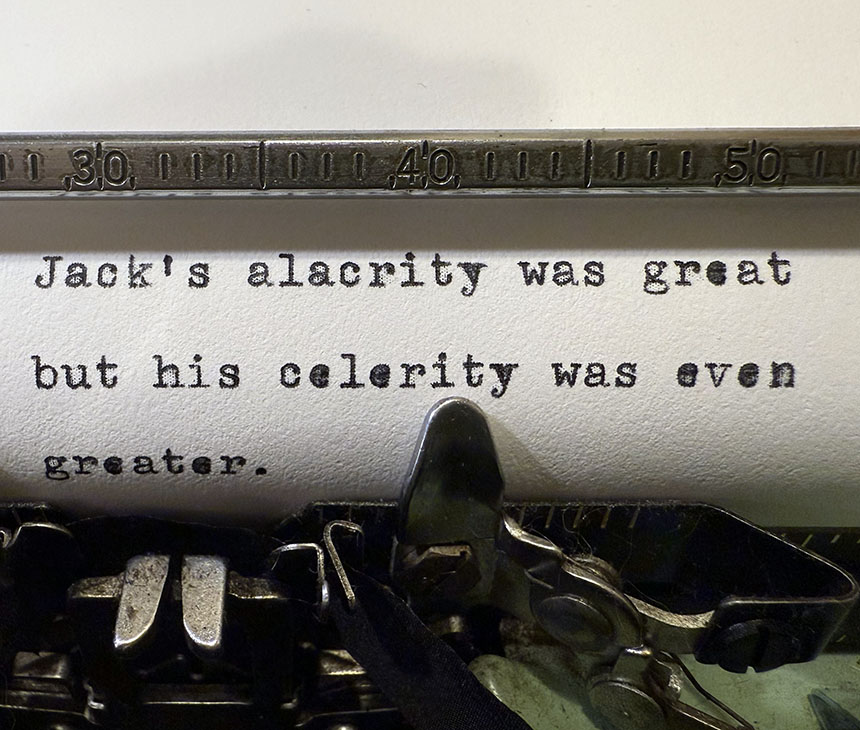

Years ago I started a list of words that a good writer would never use. Among them:

alacrity

celerity

myriad

plethora

cacophony

akimbo

acrid

stentorian

erstwhile

comprise

staccato

pulchritude

mellifluous

sanguine

lugubrious

vicissitude

recondite

effulgent

Most of these are show-off words. Bad writers think that such words make them sound smart or something.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve looked up alacrity and celerity. Useless words just don’t stick in my memory. I finally was able to remember what alacrity means because it’s related to an Italian word used in music, allegro. As for celerity, I finally figured out that it’s related to the word accelerate, so that will help me remember that one.

Most of these useless words have Latin or Greek roots, though akimbo comes from Old Norse. The proper language of fiction is plain old Anglo-Saxon. That’s one of the many reasons I love Tolkien’s writing so much. He wrote in Anglo-Saxon English, rarely resorted to words borrowed from French, and, as a philologist, he always used the right word. Imagine alacrity at Bilbo’s birthday party, or celerity in running from orcs.

Thesauruses have a purpose, but mostly, I think, they’re abused. Sometimes, when writing, one knows that there is a lightning word for what one wants to say, but the word refuses to come to mind. A thesaurus can help find it.

It’s pure abuse, though, when someone uses a thesaurus to find an uncommon word with the idea that it’s lazy to use the common word, as though all synonyms are equal. For example, not wanting to describe a shirt as green, the word verdant is lifted from a thesaurus. A variant of this I call “silly synonyms.” In my years as a newspaper copy editor, I tried to break reporters of it, but I never succeeded. That’s the idea that, having referred to a dog, the second reference must be canine, or blaze after fire. How many times have I complained, pencil in my hand, “It’s always dog, dog, dog, damn it.” The words canine and blaze are two of the best marks of a hack that I can think of.

This is on my mind because, with the help of an AI, I’ve been trying to discover authors that are new to me that I might like. Googling for book lists hasn’t worked well for me. Working with the AI’s suggestions, I’ve downloaded many Kindle samples. I fling most of the samples, because it’s apparent that the writing is poor or that the writer is just cranking stuff out. I recently read Ken Follett’s The Evening and the Morning and realized that Follett is a crank-it-out author. I strongly suspect that some of these popular writers have ghost writers who help them crank it out. For example, I suspect that S.J. Parris tried to capitalize on the popularity of C.J. Sansom. But Parris is lazy writer who is just cranking it out.

It seems that the older I get, the harder it is to find fiction that I like. Maybe that’s not surprising. There’s only so much good stuff, and after decades of reading I’ve already read a big chunk of it.

I asked chatgpt to write a short storey for me to see how it would handle it. It was actually quite readable although it was bit heavy on the purple prose.

Hi Chenda: Very interesting! I wonder what it would do if you asked it to write a short story while avoiding words with Latin roots, to see if it can write purple prose in Anglo-Saxon. If it can, that in itself would be fascinating. 🙂

Here you go 🙂 I asked it to write a short story about a women walking home across the moors to her farmhouse, and this is what it gave me. It definitely sounds better in the Anglo-Saxon version!

Mist on the Moor (Anglo-Saxon)

Meg drew her wrap close as she strode over the high moor. Day’s last light had fled, and a thick mist rolled in from the west. No moon showed, nor star — only the dark path, wet and slick with peat. The wind sang low and strange, as though it slid round her with mind and will. Oft she turned to look back, yet saw naught but the drift of grey. She stepped on more swiftly. The black swell of the hills lay ahead, and past them, the squat stead she called home. A stone rang under her boot. She stood still. The sound that came then was not her own step — soft, slow, and near. “Who goes there?” she said, though her voice was small in the wide dark. No word came. Only the thick drift of mist, rifting now and then to show the shade of a tall, lean shape, far yet watchful. Her heart beat quick. She gripped her wrap and went on, not once looking back till the warm gleam of her stead shone through the murk.

The Phantom on the Moor (Latinised version)

Margaret tightened her shawl as she traversed the elevated moor. The final vestiges of daylight had dissipated, and a dense vapour advanced from the western horizon. The moon was obscured, the stars effaced — all that remained visible was the narrow track, moist and treacherous with peat. The wind murmured in a peculiar cadence, as though it conspired to encircle her with intent. Periodically she glanced behind, yet perceived nothing but the shifting pall of mist. Her pace accelerated. The dark undulations of the highland lay ahead, and beyond them, the familiar farmhouse — her refuge. A stone loosened beneath her boot, emitting a sharp report. She halted. What followed was not her own step — subdued, deliberate, and disconcertingly near. “Who is there?” she inquired, her voice attenuated by the vast gloom. No response — only the drifting haze, which occasionally parted to disclose the indistinct outline of a tall, attenuated figure, distant yet distinctly observant. Her pulse intensified. She clutched her shawl and proceeded with unwavering resolution, never again turning her gaze until the hospitable illumination of the farmhouse shone, radiant, through the enveloping murk.

Wow! The difference is wonderful. I’d be prepared to argue that the chiefest reason for a native speaker of English to study Latin or French is to be able to sort words by their origin.

One thing I notice is the conspicuous and somewhat odd use of the word ‘stead.’ It’s Anglo-Saxon, of course, from ‘stede,’ meaning place, site, position, station. But as you know, it’s commonly heard only as part of another word, such as ‘steadfast’ or ‘steady’ or even ‘instead.’ I think ‘cottage’ probably is what is wanted here.

I admire the AI for writing ‘Her heart beat quick,’ rather than ‘quickly,’ which I think most unskilled writers would write.

Ah yes, you can see how words like ‘instead’ must have originated from it. I can see AI being a useful tool for writers to help refine their writing.

Words unnecessary:

punctilious

capacious

and others – why can’t the writer just say – he’s late, she’s late – or there’s a lot of space or thinking hard or whatever

I am still thrilled and in awe how a writer can just continue with a story that seems to flow from their pen or typewriter (ok computer). Amazing twists and turns of a story, surprise here and there