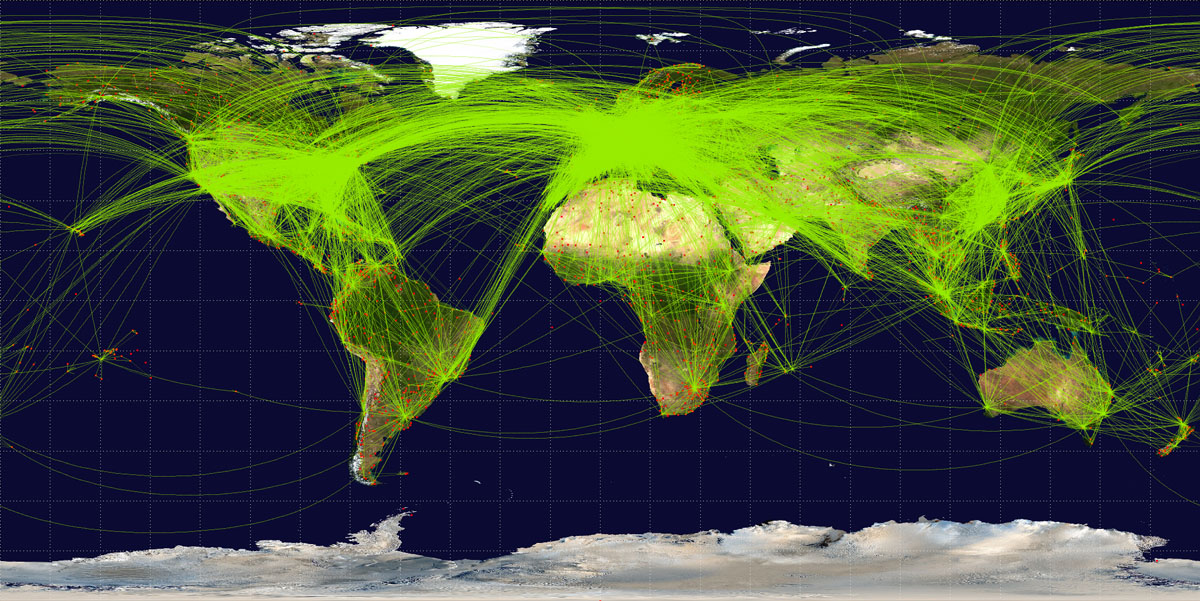

Scheduled air traffic, 2009. Wikipedia.

I owe a great deal to Nouriel Roubini. I had been a liberal prepper since 9/11. I was preparing for retirement as the Bush-Cheney financial bubble grew — and grew and grew. If you believed the horsewash and the noise in the media, it was a fine time to borrow money against your house and live it up — new cars, dream vacations, and granite countertops bought with borrowed money. I did not believe the horsewash, and I did the opposite. I got out of the stock market before it blew up. I carefully moved my retirement money out of tax-sheltered accounts, duly paid the taxes on it, and converted most of my assets into usable land and a paid-for house. I actually benefited from the financial crash, because I built Acorn Abbey during the trough of a recession, when materials prices were low and when people were hungry for work and bid low.

But my point is not just that we should be contrarians. Rather, it’s about the importance of beating the bushes for reliable information, especially in uncertain times. Much of the noise in the media comes from people who have lots of opinions, but not a lot of information. And, these days, the Republican Party and its propaganda organs just make up whatever information suits their agenda. Many people haven’t caught on to how their politics and religion can be used to take advantage of them.

But back to Nouriel Roubini. The fact that he was right about the financial crash of 2008 (and that his model was predicting it before 2006) does not necessarily mean that his current predictions will be accurate. But it does mean that he has a good model, and it does mean that we’d be wise to take his predictions seriously. His predictions are very, very scary — a global depression, a period of inflation, and even food riots.

Here’s a link to an interview in New York Magazine: Why Our Economy May Be Headed for a Decade of Depression.

One of the things we need to be trying to model right now is how this pandemic is going to permanently change the way we live. We need to be on the lookout for reliable information about what people are starting to do differently. And we need to pay attention to people like Nouriel Roubini, whose views are based on actual data and whose models are constantly updated. Data from the economic shock from Covid-19 obviously required that Roubini update his economic model. The New York Magazine piece, as far as I know, is the first piece available to the public on Roubini’s post-pandemic model.

Note the comparison to Germany in the New York Magazine piece. More than ever, we need competent government to get through what we’re probably facing.