The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. J.P. Mallory and D.Q. Adams. Oxford University Press, 2006. 732 pages.

I have a standard riddle that I thought of years ago. I don’t think anyone has ever gotten the answer:

Name something that you use every day and that you couldn’t get by without. It has never cost you anything. It was made by humans. It is thousands of years old. What is it?

The answer, of course, is language. We totally take language for granted, like free air, free water, and free cats — all of which we’d be willing to pay huge sums for, if they were scarce. (People are already figuring out how to get us to pay for water. As for cats, mine was free, like all the best things in life. This time of year, you can probably get as many free cats as you want, if you’re in need of some.)

Language is an incredible gift left to us by our ancestors. But even as we use that gift, we quickly forget our ancestors. In The Horse, the Wheel, and Language, David W. Anthony points out that many of us can’t even name all four of our great-grandmothers. That’s how fast we lose knowledge of the past, at least in most western cultures. As an elder, one of the things I’ve noticed about young people — for example my own great-nieces and great-nephews — is that they rarely express any curiosity about now-dead relatives that my generation remembers and could tell them about, if they cared to know. In only three generations, most of us will be forgotten. That’s our payback, I suppose, for forgetting those who came before us.

As I have gotten older, I have become increasingly curious about my ancestors, whose experience probably was very similar to that of your ancestors. My curiosity has been inflamed by the cultural destruction that has occurred during the Christian era, which has made it much more difficult to imagine how our ancestors lived. Those who have read this blog, or my novels, are aware of my rage at the cruelty, and ugliness, and completeness, of Christianization. Except for a very few traditions such as a midwinter pagan festival, which we now call Christmas, our memory of the pre-Christian past is gone, like the memory of our ancestors. One might accuse me of romanticizing the pre-Christian past. Not by any means do I suppose that the pre-Christian past was a utopia. But I do think it’s clear that Christianity systematically demonized and disenchanted the natural world, replacing the collective wisdom of our ancestors with theologies and texts from old cults that are shocking in their poverty and infantility. We are the way we are today because we’ve forgotten any other way to be. I strongly suspect that humanity’s survival depends on whether we can regain an awareness of our dependence on the natural world and find a way to re-enchant and preserve the natural world.

The trajectory of Christianization, unsurprisingly, included the extinction of languages. In the case of the Mayan hieroglyphs, much of the destruction was intentional and was the work of a single Catholic priest. The extinction of Gaulish probably was more a product of Romanization than of Christianization, but in the last years of the empire there was not much difference between Romanization and Christianization.

Still, even robust living languages and their words and grammars are largely fossils, with components that are extremely old. In the last 200 years, historical linguists have developed methods that are remarkably good at tracing a language backward toward its roots. This brings us to the now-extinct language that we call Proto-Indo-European. Though it is a dead language, more than half the people on the planet today speak a language that is descended from Proto-Indo-European. Modern descendants include most of the languages of Europe and some of the languages of Asia, such as Hindi. Classical languages including Greek, Latin, the Germanic languages, the Celtic languages, and Sanskrit are all descended from Proto-Indo-European. Strangely enough, Latin and Celtic are actually close cousins in the Indo-European family tree, because the Romans and the Celts were neighbors in Western Europe. It was not until the 18th Century, as Europeans started encroaching on India, that Europeans discovered that Sanskrit is a relative of Latin and Greek and of the entire Indo-European language family.

Consider the family tree of English. English is a Germanic language brought to Britain by the Saxon people, who came from what is now northern Germany and Denmark. After the Norman Conquest, as elites from what is now France gained power in old England, they brought with them a huge vocabulary of Latin words that were assimilated into English. Today, the 1,000 or so most commonly used words in English are Anglo-Saxon, but as word use expands beyond those 1,000 common words, Latin, French, and Greek start to predominate.

What makes The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European such a fascinating book is that it explains how linguists have actually reconstructed much of the grammar and vocabulary of the now-extinct Proto-Indo-European language. You’ll need to read the book to get a feel for how this is done, but obviously it involves patterns in how languages change, looking at similarities in all the surviving Indo-European languages. (Though classical Greek, Latin, and Sanskrit are considered dead languages, they are very well preserved and well understood through a large body of surviving literature.) The book actually contains lists of reconstructed words in Proto-Indo-European, with the equivalent English word. These lists run to 100 pages! Can linguists be absolutely sure that they’ve reconstructed these words? Of course not. But confidence is high. One linguist claims to have used the same techniques to reconstruct Latin by working backwards from the Romance languages, claiming to have reconstructed the Latin vocabulary with 95 percent confidence and Latin grammar with 80 percent confidence.

There are a great many reconstructed words from Proto-Indo-European that speakers of English will recognize, such as mūs for mouse, or werĝ for work. If you speak a modern Romance language, then you will recognize many more.

So, what do the fossils in our language tell us about our ancestors? We can learn a great deal, obviously, from what they did or did not have words for. We know that the people who spoke Proto-Indo-European, from about 4000 BC to about 2500 BC, had words for horses, for farming equipment such as plows, for oxen and sheep, for wool, for milk, for weapons, for barley, for beer and mead, and for wheels, axles, wagons, and for all sorts of wild plants and animals. Archeologists tell us that Europeans before 8000 or so BC were foragers. It is safe to assume that the Proto-Indo-European language spread across Europe and parts of Asia as farming and herding spread and as people stopped foraging for a living. Still, even as people settled down to farm, there was still a good deal of travel. There are Proto-Indo-European words for roads, wandering, going astray, and hospitality. As the people settled into agrarian lifestyles, and as cities developed along the rivers and coasts, the Proto-Indo-European language began to divide into Germanic, Greek, Latin, Celtic, and so on. The process must have been very similar to how Latin divided into the Romance languages after the fall of Rome.

Linguistics, then, can tell us much more about our ancestors than we might at first think. There are some questions, though, to which linguistics cannot provide a definite answer. One of those questions is where the Proto-Indo-European language originated and what the migration routes were. As far as I can tell, scholarship that combined linguistics and archeology to shed light on the lives of early Europeans was fairly late to develop. As of now, the best book I know of on this subject is from 2007: The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders From the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. I’ve just started reading this book and will plan to review it later. But I want to mention four books here that I have chosen to help me get a feel for how the English we speak today can be traced backwards to the lives that our European ancestors lived up to 8000 years ago, and the languages they spoke. The other three books are listed below.

J.R.R. Tolkien, you will recall, was an Oxford philologist. It is very easy to romanticize prehistoric Europe as being a lot like Tolkien’s Shire, with the land of Rohan and its horse lords being a lot like the plains (or steppes) of eastern Europe and western Asia.

Despite its length and the technicalities of linguistics, this book is surprisingly easy to read. The only thing that stumped me — the same way that the math in books on physics stumps me — is that I mostly cannot follow the marks that linguists use to indicate pronunciation, or all the terms that linguists use for different types of vocalizations, such as labials, dentals, palatals, velars, labiovelars, sibilants, laryngeals, nasals, semi-vowels, etc. You’ll be able to follow the gist of this easily enough, though. I recommend watching some YouTube lectures on Proto-Indo-European, in which the speakers are linguists who have an incredible ability to produce the sounds that occur in human languages.

⬆︎ The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders From the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. David W. Anthony. Princeton University Press, 2007. 554 pages.

I’ve just started reading this book and will have a report later.

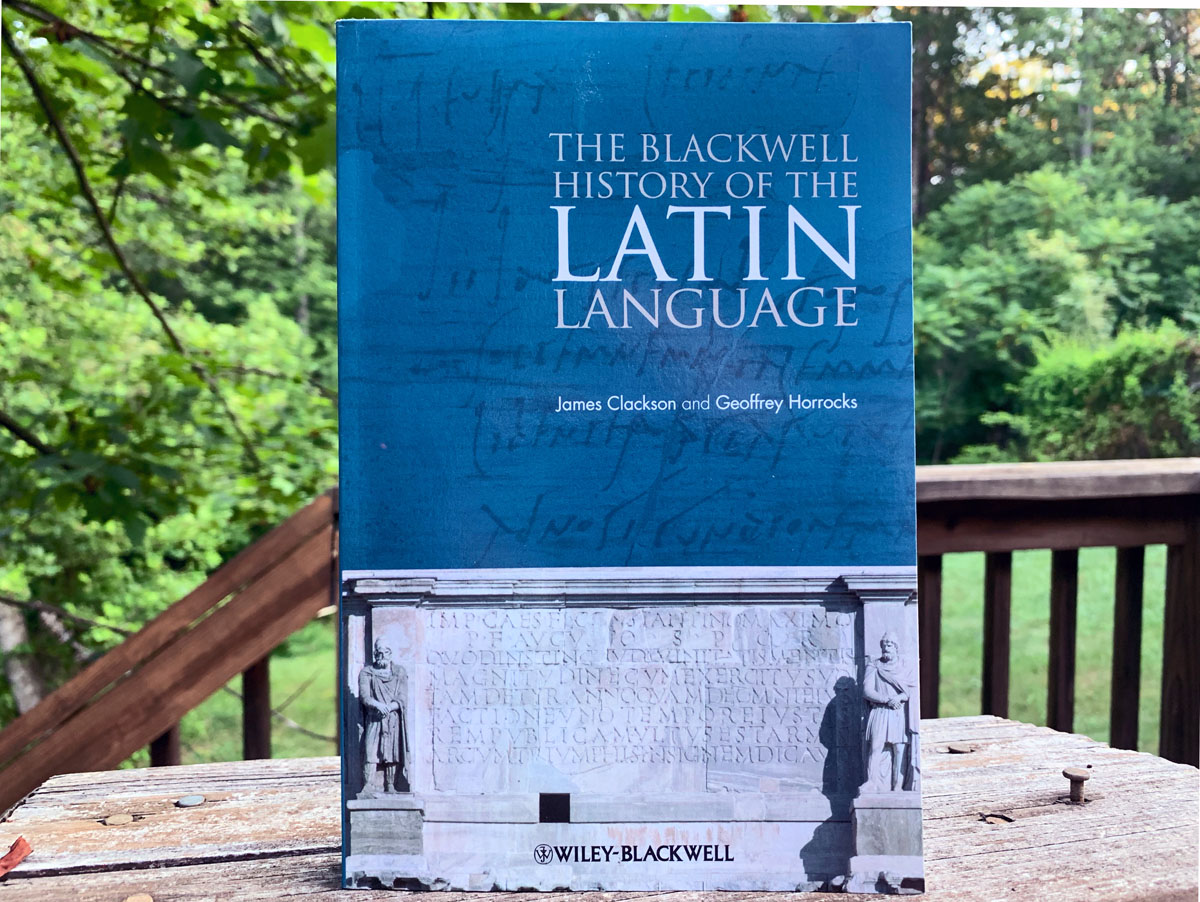

⬆︎ The Blackwell History of the Latin Language. James Clackson and Geoffrey Horrocks. Wiley-Blackwell, 2007. 324 pages.

I will read this book after The Horse, the Wheel, and Language. I’m curious to know how Latin differs from Proto-Indo-European, and maybe why. We do know that Proto-Indo-European had a complex case system, like Latin. But what puzzles me is why speakers of languages such as Latin put up with such complexity. We know that the Romance languages (French, Spanish, Italian, etc.) started out as dumbed-down Latin. All, or least most, of the Romance languages trashed or greatly simplified Latin’s six cases of nouns — nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, ablative, and vocative. It makes me dizzy just to list them.

⬆︎ The French Language. Alfred Ewert. Faber and Faber, 1933. 440 pages.

I’ve had this book for a good many years. After I learned to read French, I became curious about how French had developed from Latin. For example, where did those weird nasal vowels in French come from? Ewert attributes such things to “the persistence of linguistic habits of the Celtic population,” which is hardly surprising. But you can see that I am trying to work backward on the English branch of the language tree: English -> French -> Latin -> Proto-Indo-European. I wish I could read German. Alas, I cannot.

Here’s a little puzzle for you if you’ve read this far. Do you know the meaning of the English word adumbrate? If you do, you can give yourself an “A” and skip the next paragraph. Otherwise, let’s puzzle out how you can figure out what adumbrate means without having to go look it up.

To figure it out, you don’t even need to know the meaning of the Latin infinitive adumbrare. Nor do you need to know that the Latin word adumbrate (it’s four syllables in Latin, ah-doom-brrah-tay, I think) is the masculine participle of the verb adumbrare in the vocative case. All that is good to know. But a language-lover will see the three parts of the English adumbrate without even slowing down in reading. There is the prefix ad-, the root umbra, and the suffix –ate. I bet you’re onto it already, because you know what an umbra is — that which an umbrella has underneath it. The Latinate prefix ad– means to go toward or to draw to. The root umbra means shadow. The suffix –ate turns the word into a verb. So, adumbrate means to throw something into shadow.