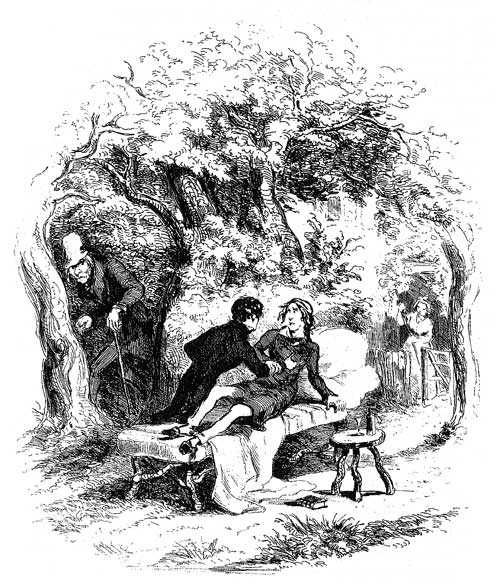

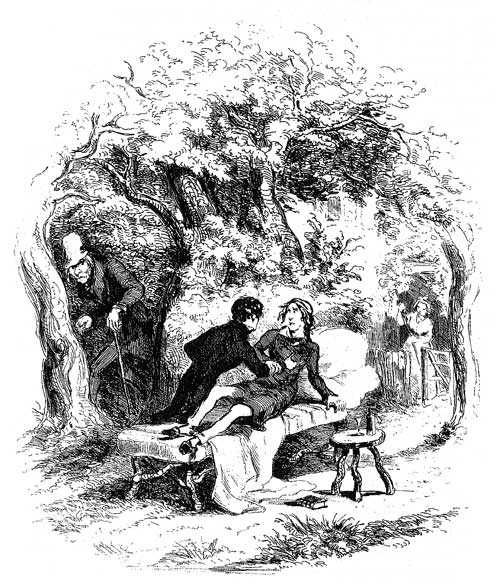

Smike on his deathbed, dying of consumption — Nicholas Nickleby

It’s a dark pun, but the people of the 19th century, and we in our own time, are stalked by the same wasting disease that leads inevitably to ruination if not death — consumption.

Today is “black Friday.” The media (feeding the frenzy while pretending to cover it), is already full of horror stories. At a Walmart in Los Angeles, a woman shot pepper spray at 20 people so that she could grab the consumer goods she wanted first. At a mall in Fayetteville, North Carolina, there was gunfire. Last year, as I recall, people were trampled in stampedes when Walmart opened its doors.

These people were not looking to feed their families. They were looking for stuff, stuff that will be in landfills in a few months.

And here is yet another story from the right-wing blogosphere on how ill-prepared Boomers are for retirement. Fifty-six percent of retirees have debt. Forty percent of Boomers plan to work “until they drop.”

Metaphorically, at least, they are dying of consumption. How can they know so little about personal finance? I was stupid with money too when I was young, but I came to my senses around age 40 when I realized that I actually would be old someday (young people think that growing old is impossible). And I realized that I did not want to work for the rest of my life.

Strangely enough, we could learn much about personal finance from our archenemy — corporations. I’m talking about honest corporations, of course, not those that are looted in leveraged buyouts or executive scams.

I was lucky to have worked for a good corporation for the last 15 years of my working life — the Hearst Corporation. Hearst is a private corporation, so it doesn’t have to worry about a stock price and kiss the behinds of Wall Street. It was cash rich and, at least I was told, never borrowed money. It always spent cash. It didn’t lease — it bought outright if it needed something. And I was told that it didn’t even buy insurance, because the corporation had enough cash to be self-insured.

For years, I had to create budgets for my department and get them approved. I was in San Francisco, but the main office in New York approved the budgets. I never ever, in my career, went over my budget, though other managers sometimes did. It was a point of pride for me — to be able to anticipate my needs for the next year, to budget for those needs, to justify the costs, and then to stick to it.

There is a very important principle in how corporations handle money that every household would do well to keep in mind. That’s the concept of expenses versus capital improvements. Corporations do it that way because of tax laws that don’t apply to households, but the principle is still valid.

Expenses are roughly equivalent to consumption. Expenses, for a household, are things like electricity, groceries, gasoline, clothing, gadgets, etc. You can’t live without incurring expenses, but if expenses are not controlled they will eat your income and prevent you from making capital improvements and prevent you from accumulating assets. Expenses are the money we pee away. Expenses drain our income and do nothing to improve our future.

Capital improvements have to do with things that last a long time and that improve your quality of life. One’s house is the main capital item. A car is another. Even a washing machine is a capital item. A Jaguar, though, is not transportation. That’s a luxury. When you spend capital, you determine what meets your needs and buy that much, no more. Where cars are concerned, for example, the right solution for me was a Jeep, which was a good San Francisco vehicle because it’s short and has real bumpers, and also a good country car, because I now live half a mile down an unpaved road, in the boonies. Similarly, a McMansion is not a dwelling, it’s a wasteful luxury. I have found that 1,250 square feet is more house than I need most of the time. Money well-spent on capital needs also can reduce your future expenses and thus help pay for itself — gas-frugal cars, for example; or energy-efficient houses; or an efficient new heat pump to replace an old, energy-hogging heat pump. In a corporate budget, a capital item must be “justified.” It has to make sense when you do the hard-nosed, cold-blooded number crunching. It has to get past the “bean counters,” as we called them.

If you look at how chronically poor people spend their money, you’ll usually find that they are pissing away their income on consumption and wasteful “expenses,” leaving no surplus for capital improvement and asset accumulation. And, when they incur debt to acquire a capital item, they tend to buy far more than they need because they bought what they wanted rather than what they needed and could justify.

It used to be, in this country, that the centerpiece of household finance was to buy a house with a 30-year mortgage, pay it off, and then retire in that house, mortgage free. The abandonment of that idea is one of the things that is killing the middle class. People started drawing on the equity in their homes to increase consumption. Even when they spent that equity on their homes, it was on stuff that cannot be cost-justified, like granite countertops. Thus they end up with no assets, debt that financed consumption, and out-of-control expenses for processed food, eating out, gadgets, gas-guzzler gasoline, cable television, and stupid luxury items that they saw on TV.

I often tell any young person who will listen the two most important things about personal finance that I ever learned: You must spend less than you make, substantially less when possible. And you must accumulate, else you will have to work forever.

And if I was made dictator for a few seconds, long enough to be granted one wish for my pathetic fellow Americans, it would be this: I’d cut off their cable. That would save them $150 a month while cutting off their access to propaganda and advertising. It also would kill a few corporations that deserve to die — Fox, for example.

But let’s learn from our enemy — corporations, the very people who sponsor the propaganda and the advertising. Again, I’m not talking about scam corporations like Enron. I’m talking about real businesses that actually do productive things and make money at it. They are usually very prudent and hard-nosed in how they spend their money. And that’s one small reason why they are rich and we are not.