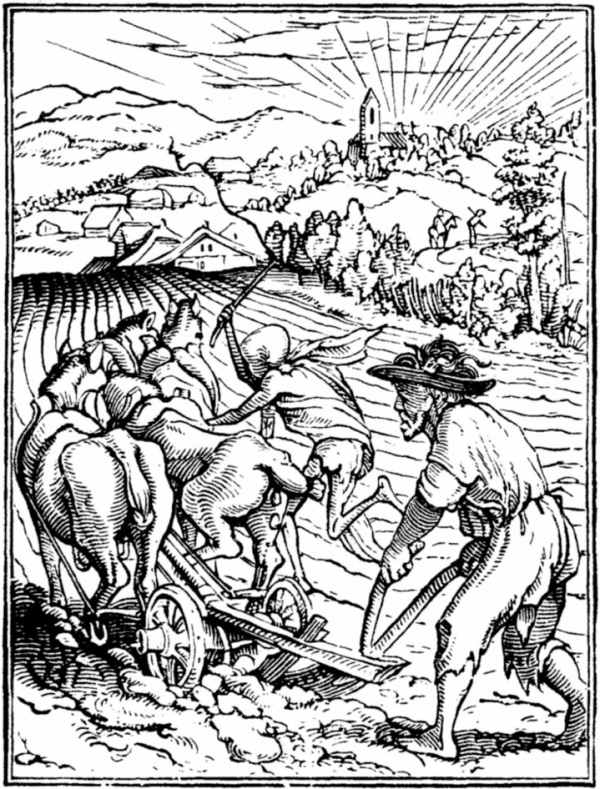

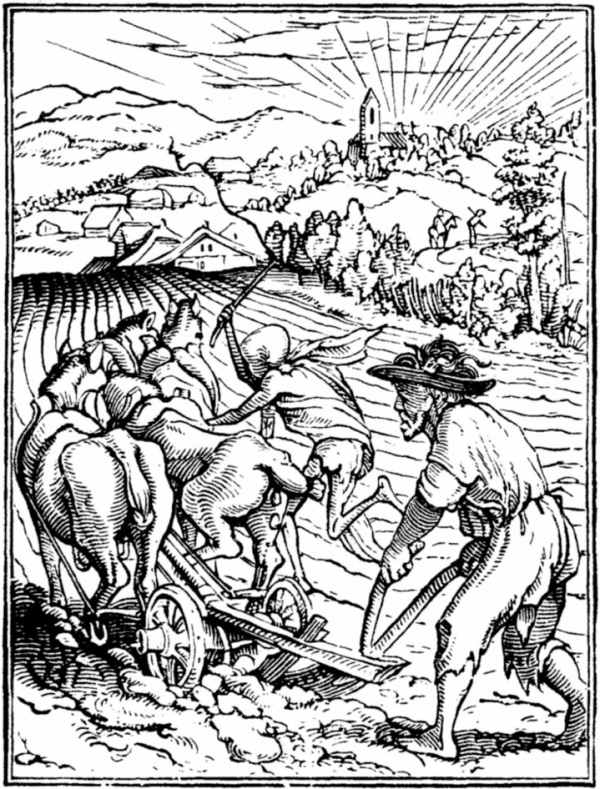

Hans Holbein the Younger, “Death and the Plough”

Part of getting older, I think, is to increasingly wonder how the world came to be the way we found it. To answer some questions, to try to get to the roots of culture, one must go back a very long time. Just now I’m trying to better understand what happened after the fall of Rome.

Most histories of Rome leave off around 410 A.D., when Alaric I, king of the Visigoths, thoroughly sacked Rome. Or 476 A.D., when the last western emperor was deposed by a Germanic chieftain. What happened then? How did the conditions of medieval Europe unfold out of the ruins of Rome?

I just finished a book on this period. It’s The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization, by Bryan Ward-Perkins, Oxford University Press, 2005.

With historians, there are trends. For example, a history of Rome written a hundred years ago will probably be an administrative and military history of Rome. The Roman record will be accepted with little challenge and skepticism, and profound questions probably will not be asked.

According to Ward-Perkins, a new trend of Roman histories arose starting around the 1960s. Many historians of that era questioned whether Rome really fell at all. Rather, they saw medieval Europe evolving or “transforming” smoothly and nonviolently into the medieval world. Ward-Perkins does not agree with that view, and the purpose of this book, really, is to challenge that idea.

Ward-Perkins does this partly by invoking the archeological record. Much of this archeological work is new and was not available to earlier historians. It is dull data, but very revealing:

— Coins: How many were found, and when, and where?

— High quality pottery: Who had it, who didn’t and when did it disappear?

— Cattle: How fat were they during the pre-Roman, Roman, and post-Roman eras? (This can be determined from the bones.)

— Tile roofs: Who had them and who didn’t, and when did they disappear?

— Buildings: How big were they, and were they made of timber, or stone?

We know that, by the 6th century, Germanic tribes had moved into the Roman territories and had taken control — the Lombards into Italy, the Franks into northern France, the Saxons into southern and eastern Britain. The Roman army was no more. The Roman administrative system also was dead, the system that had kept the trade routes open, the infrastructure working, and merchandise flowing into the provinces along the Roman roads. The provinces were now on their own, with new Germanic chieftains in control.

Ward-Perkins’ view is that what happened from the 6th to the 8th century was not a smooth “transformation.” It was a catastrophe. The food supply, which had depended on trade and shipping, dropped sharply. In some areas, for lack of food, the population fell by as much as 75 percent. Coins vanished. No one had good Roman pottery anymore. Buildings became small, and they were built of perishable materials like wood and thatch. Cattle, which had been big and fat during the Roman era, became fewer, and skinny. The archeological record shows that people became poor and miserable. There was widespread violence, strife, and crime.

Adaptation to the new conditions was slow. Some technologies that were lost (such as high quality pottery made on a wheel) did not reappear again until centuries later. Food production did not return to Roman levels until centuries later. Literacy collapsed. The security and order that had been maintained by the Roman troops was gone. In Ward-Perkins’ view, what followed the fall of Rome truly was a dark age.

Ward-Perkins elaborates on the price of specialization and complexity in the Roman economy. Even in the more remote provinces such as northern France and Britain, people did not need to produce locally everything that was needed because so much could be bought so cheaply from so far away and brought in over the Roman roads, or by ship. When that was no longer possible, the improverished and now isolated local people found that they no longer had the skills and infrastructure to produce what they needed to maintain anything like their former standard of living. It took centuries to recover those skills. Until those skills were recovered, there was deprivation and misery.

Ward-Perkins does not use the term, but one could say that the Dark Ages were a period of relocalization following the failure of what was, for that time, a globalized economy.

Ward-Perkins writes:

“Comparison with the contemporary western world is obvious and important. … We sit in our tiny productive pigeon-holes … and we are wholly dependent for our needs on thousands, indeed hundreds of thousands, of other people spread around the globe, each doing their own little thing. We would be quite incapable of meeting our needs locally, even in an emergency.

“The enormity of the economic disintegration that occurred at the end of the empire was almost certainly a direct result of this specialization. The post-Roman world reverted to levels of economic simplicity, lower even than those of the pre-Roman times, with little movement of goods, poor housing, and only the most basic of manufactured items. The sophistication of the Roman period, by spreading high-quality goods widely in society, had destroyed the local skills and local networks that, in pre-Roman times, had provided lower-level economic complexity. It took centuries for people in the former empire to reacquire the skills and the regional networks that would take them back to these pre-Roman levels of sophistication.”

That, I believe, is stuff worth thinking about.