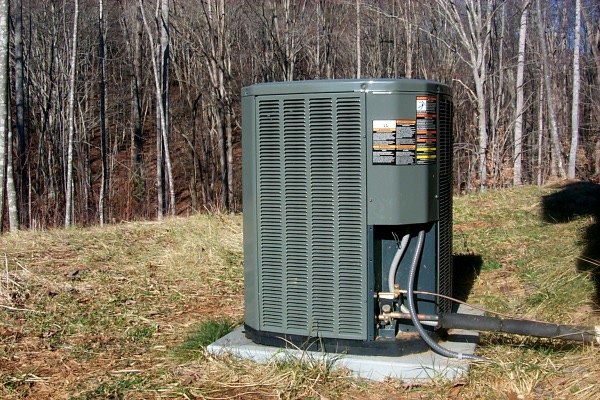

The compressor

It’s cold outside, so let’s talk about heating systems.

Over the years, I’ve lived in houses with all kinds of heating systems — wood stoves (including wood cookstoves), wood circulators, oil circulators, oil-fired furnaces, gas-fired furnaces, and, in San Francisco, electric baseboard heaters. The heating system that I remember most fondly (other than the wood cookstoves) was a system that used steam radiators and a gas-fired boiler, vintage 1935 or so. A friend of mine even named the old boiler Puff.

The gothic cottage has a heat pump (a Trane XR13, model number 4TWR3030A1000AA), and these past few months have been my only experience with heat pumps. I’ve been eager to see how it performs and how much electricity it uses. It’s also a complicated system with considerable nerd appeal, not least because my system is zoned. That is, though I have only one heat pump, I have thermostats upstairs and downstairs. A Honeywell zoning system electrically opens and closes ducts to direct hot or cool air where it’s needed.

So how do I like heat pumps? Great — until the outdoor temperature drops below about 17 degrees Fahrenheit, below which temperature the heat pump efficiency clearly falls off rapidly. I’ve been observing the system carefully, paying attentions to questions such as: How cold is it outside? What are the thermostats’ settings? How often and how long does the system run? How warm is the air coming out of the ducts? Surprisingly (surprising to me, at least), the system works quite well even when the outdoor temperature is in the 20s. It goes without saying that if the temperature outdoors is in the 30s or 40s, the heat pump heats effortlessly.

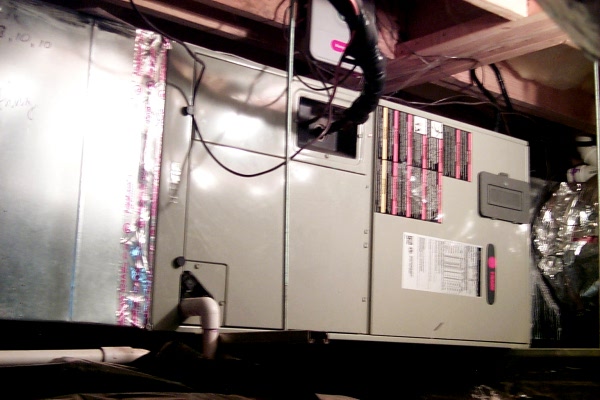

But the low here last night was 13, and the night before, 11. At those temperatures the heat pump really labors and runs most of the night. Both mornings, the thermostats have indicated that the heat pump’s “auxiliary heat” system had kicked in. To compensate for the poor efficiency at low temperatures (which heat pump manufacturers certainly understand), heat pump systems have electrical coils in their air handlers which kick in when the heat pump alone is unable to maintain the temperature requested by the thermostat. The auxiliary heating coils use three to four times more electricity per unit of heating that the heat pump, so they’re switched on only when necessary.

Just what is a heat pump? It’s like an air conditioner, with a compressor and refrigerant. But unlike an air conditioner, it can switch into reverse and can either heat or cool. The system consists of two units — the compressor, which is always outdoors; and the air handler, which is inside the house somewhere, often in a basement or attic. The air handler contains blowers, a heat exchanger for the refrigerant coming from the compressor, and the backup heating coils.

As an air conditioning system, heat pumps are great, and they have no greater problem with efficiency than any other air conditioner. But when you use a heat pump for heat, you want to be aware of how its efficiency falls off at extremely low outdoor temperatures.

With a heat pump, you almost certainly want a secondary source of heat. I have a propane fireplace. The fireplace works even during power failures, so it serves as an emergency heat source. But on those cold mornings when it’s 14 degrees outdoors is a great time to turn on the propane fireplace to give the heat pump some help.

If you’re bored some cold morning, why not watch your heat pump do its steam punk defrosting trick? The coils on the outdoor compressor get very cold when the system is pumping heat into the house. Frost forms. This frost must be periodically melted off. I am not yet sure how my heat pump decides when to go into defrost mode. I need to call my installer and find out. But I understand that there are two ways this is done. Some heat pumps defrost every so many minutes, and others have ice detectors on the coils. In any case, when this mode begins, you’ll see heavy white frost on the outdoor coils. The fan shuts off, and the compressor runs in reverse, so that the coils are producing heat rather than cold. Meanwhile, back in the house, the thermostats say “Waiting…”, and the air handler will continue to send “auxiliary heat” into the house if needed. Outside, as the coils heat up, water drips, and the ice melts away. After a few minutes, a cloud of steam begins to pour out of the compressor. When the defrost cycle is done, there is a steam-punk pneumatic hiss, like a steam train, as valves open to reverse the compressor back into service. The fan turns back on, and the compressor goes back to work pumping heat into the house. Very entertaining!

I’ve written previously about the steam punk movement.

The air handler, Trane model number 4TEC3F30B1000AA

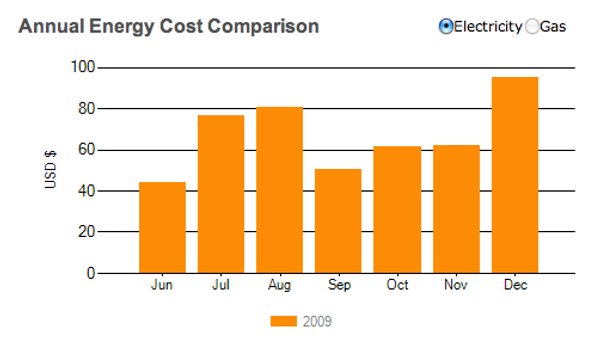

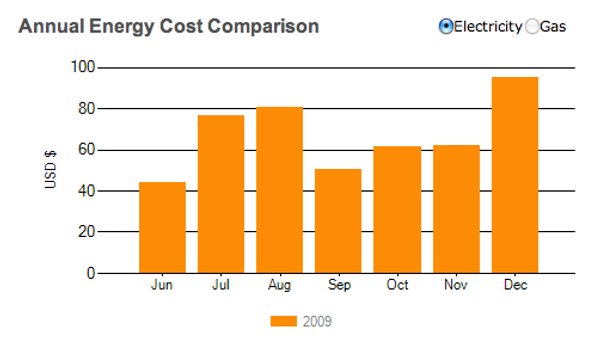

I upload data on my electricity use to Microsoft Hohm. My electric bill for December was on $94. This month has been very cold, so I’m sure I won’t get off so easy with my next bill. June was the month the system first came on line, so the June bill was for only part of a month. For a mild month like September, my electrical bill was $53. That includes, of course, lighting, cooking, hot water, appliances, and computers.