Click here for high-res version

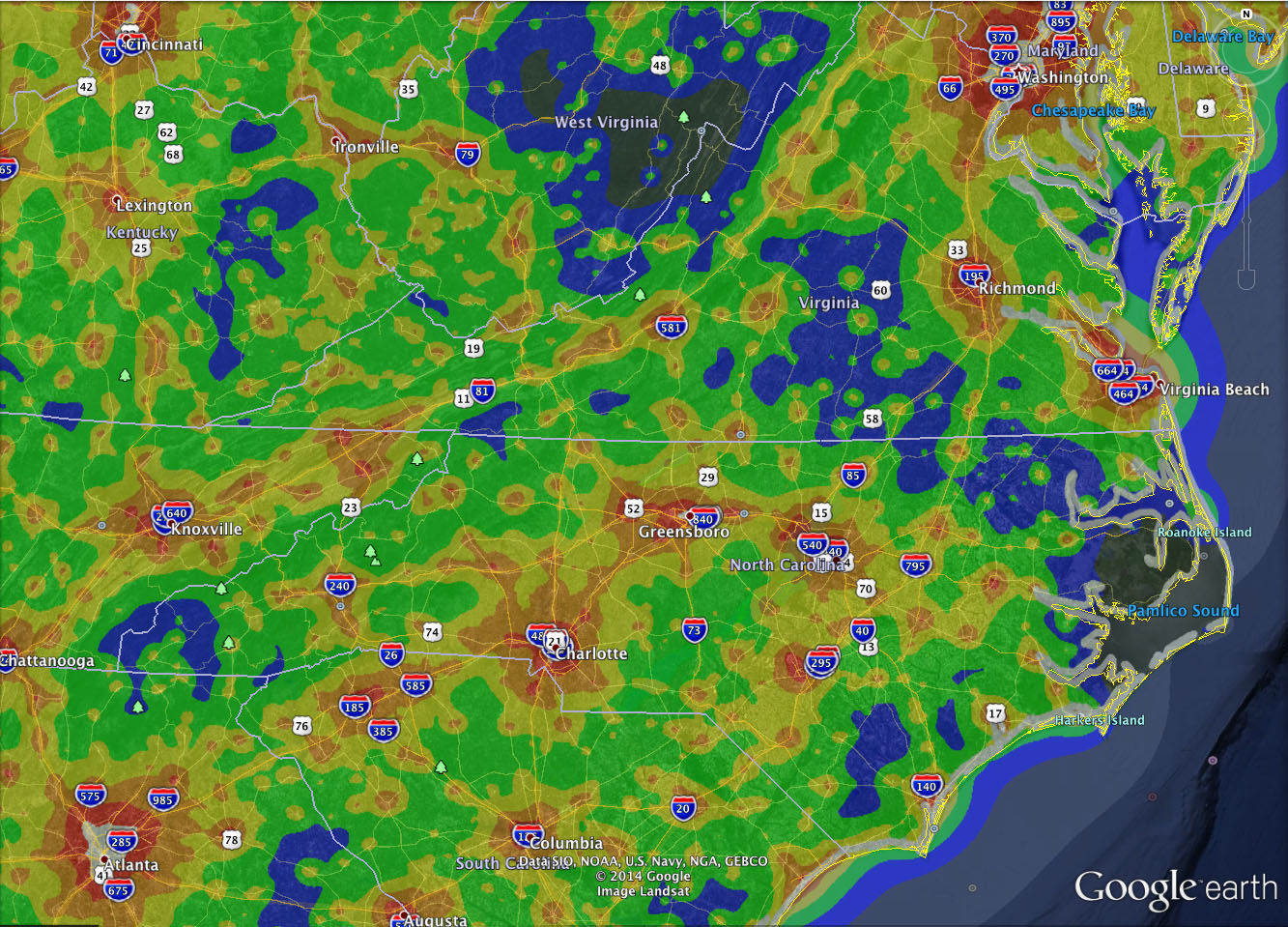

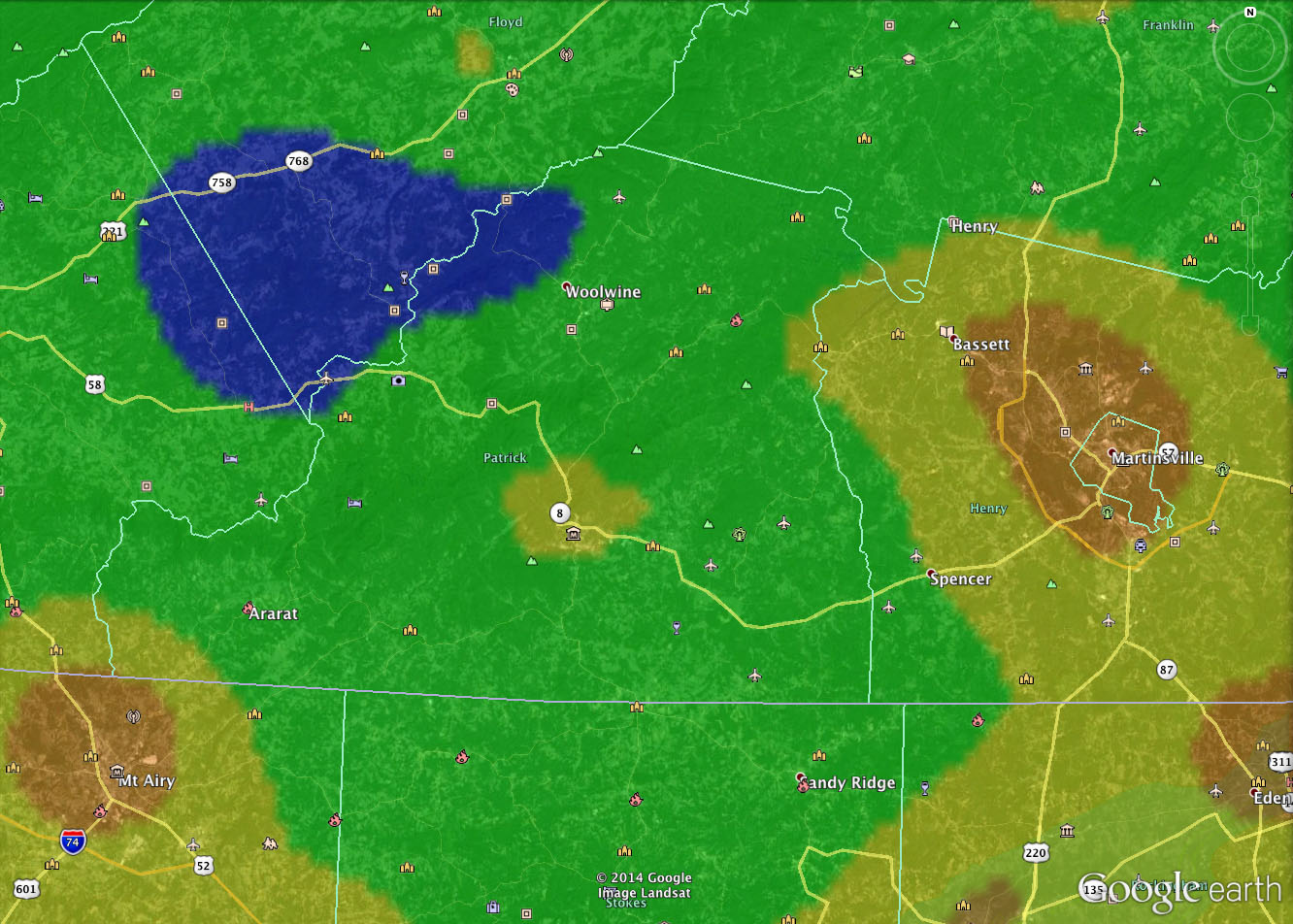

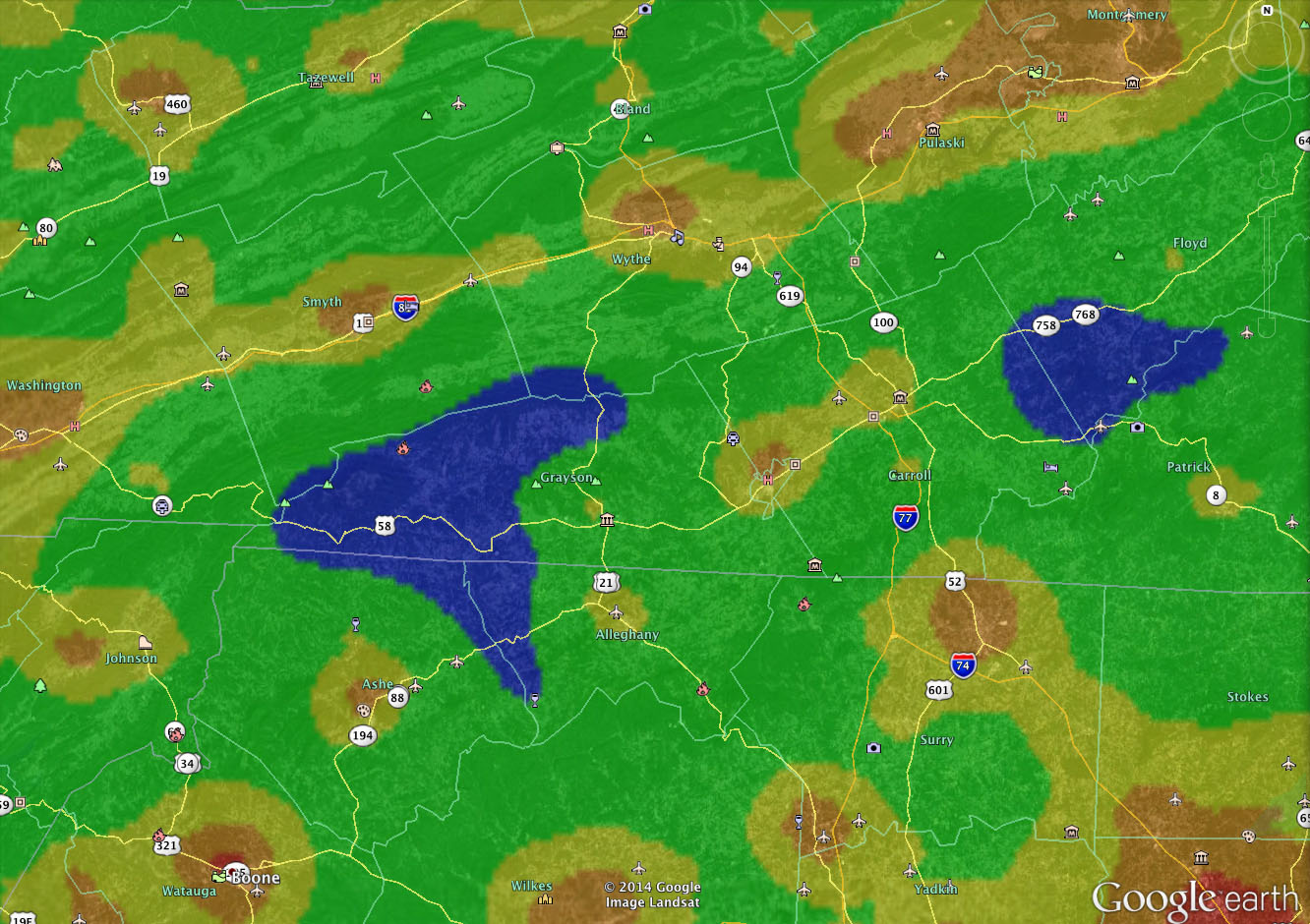

My county, Stokes County (North Carolina), is a county of rolling hills and forest, with a few small and picturesque mountains, in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, which of course are a part of the Appalachian chain. Stokes was never a prosperous county. There were a couple of big plantations (Hairstons and Daltons), but most people lived by subsistence farming, with tobacco as the cash crop. Though Stokes County now is in the middle of nowhere, during the American colonial days, and into the 19th Century, one of the most important roads in the colonies passed right through here, just over the southeast ridge near the abbey. That was the Great Wagon Road from Pennsylvania to Georgia, used by armies and by George Washington. When I drive down Dodgetown Road on the way to Whole Foods in Winston-Salem, I am on the Great Wagon Road. Ken’s jogging circuit includes the Great Wagon Road.

The house in the top photo mystifies me. It sits on a hill just above the Dan River, very near the place where the Great Wagon Road crossed the river, two miles from the abbey. It’s too elegant to be a farmhouse. There were few, or no, rich farmers here other than the plantations. My theory is that this house was an inn on the Great Wagon Road. I may be deceiving myself, but I suspect that the house is that old. I’ve sent an email to a friend who is president of the county historical society. I’m guessing that she will know the house’s history.

What’s remarkable is that the house is still lived in. Most of the old wood-built farmhouses were long ago abandoned to rot and have fallen down, along with their beautiful old barns and outbuildings (which I remember from my childhood). But at this old house, there was smoke coming from one of the chimneys this afternoon. There are lace curtains in the upstairs windows. There are horse tracks on the unpaved road in front of the house, and the adjoining pastures are clearly in use. There are no no-trespassing signs, but there is a makeshift drop-down gate made of a hand-hewn log over the driveway. This fascinates me. Someone is still living the old lifestyle. I am determined to find out who they are and what their story is.

On the East Coast of the United States, timber was (and still is) plentiful. There was little reason to build with stone when wood was so much cheaper. The downside of that is that we lose our architectural history so much quicker. Buildings rot away soon after the roofs fail. The old house above has an old, and possibly its original, galvanized steel roof, but the roof looks to be in good shape. I believe galvanized steel was invented in 1836, though I don’t know when it became available in this area.

The stone construction in the lower photo is an iron furnace. It’s at Danbury, about five miles from the abbey, right beside the Dan River. It was in service during the Civil War days, casting munitions. It also produced iron bars and such for the use of blacksmiths. Not a stone has fallen, as far as I can tell. Early Americans knew how to work with stone, but usually they didn’t. Even when they eschewed wood as a building material, they used brick, as at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and in colonial towns such as Williamsburg (Virginia) and Salem (North Carolina). Still, wooden buildings can last a long time if their roofs don’t fail.

People who know some local history ask me how I (my last name is Dalton) am related to the Daltons of the Dalton plantations here. The answer is that I am not descended from those Daltons but that we are all descended from the same line of Virginia Daltons. (It always amuses me to type that, because my mother’s name was Virginia Dalton.)

My eighteen years in San Francisco were great. But I love living in the middle of nowhere, in the woods, as good a place as any in the U.S. that suburbanized modernity has passed by.