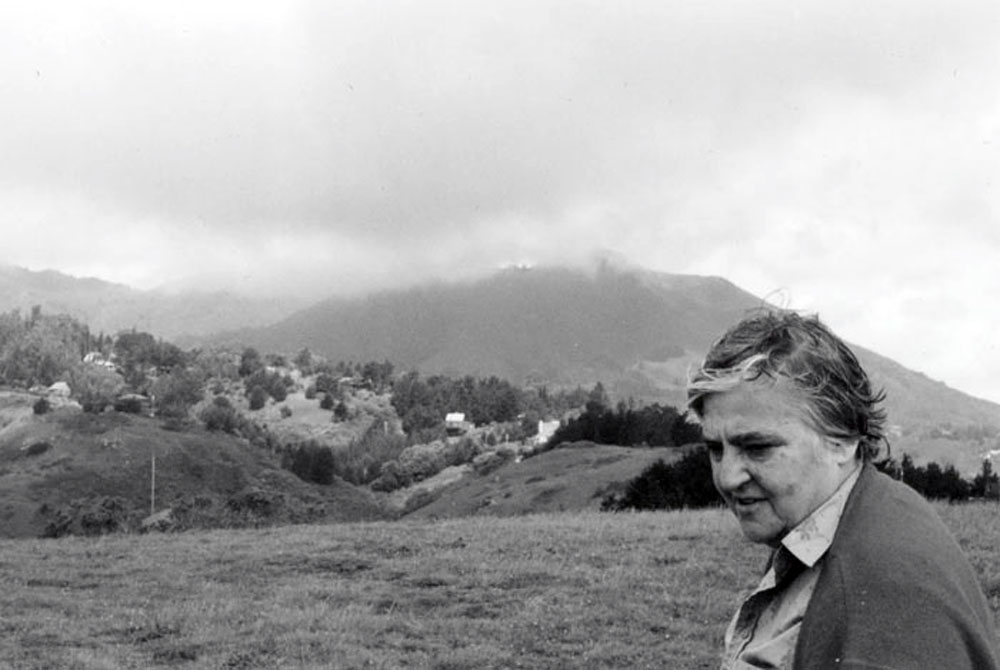

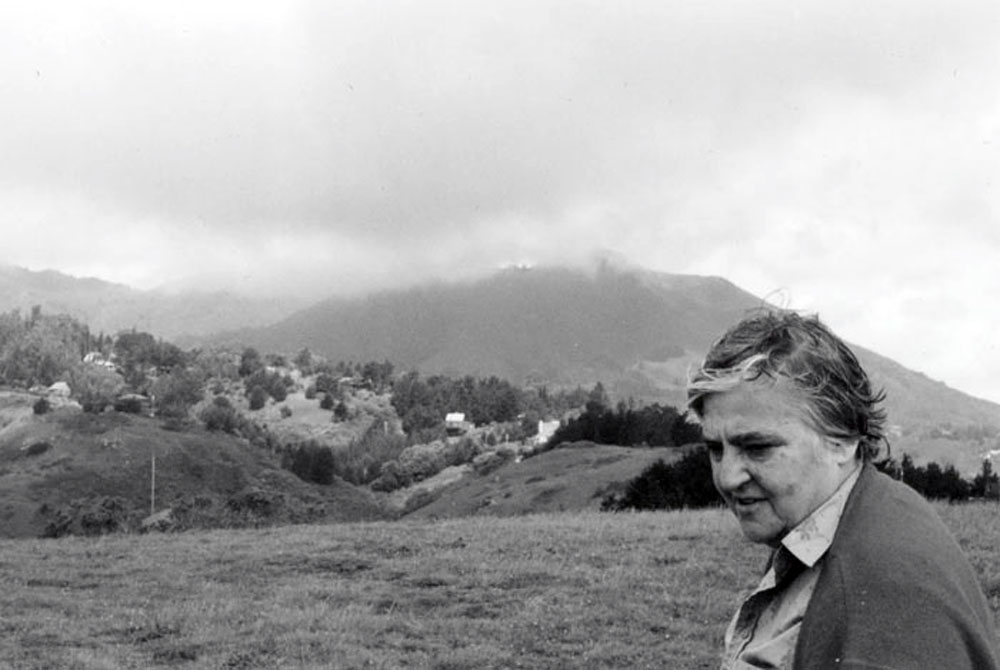

Etel Adnan in Marin County, California. Photo by Simone Fattal. Source: EtelAdnan.com.

The New York Times carried an obituary this morning for Etel Adnan, who died yesterday in Paris at the age of 96. I was saddened to hear this, because I knew Etel and her partner, Simone Fattal, during their Sausalito years, when I was living in San Francisco.

Etel was best known for her novel about the Lebanese civil war, Sitt Marie Rose. Part of what I find remarkable about Etel Adnan is how her literary reputation was built entirely on the work of small presses. As far as I know, none of her books was ever published by a commercial press. Etel and Simone had established their own micropress during the 1980s, the Post-Apollo Press. It was Post-Apollo that published Sitt Marie Rose, translated from the original French by Simone. Even in the early ’90s, inspired by Simone and Etel, I aspired to starting a micropress someday.

When I reflect on what I remember about Etel, what stands out is her sadness and grief about what civil war did to her country, Lebanon, and in particular to the immense damage of what war did to the city of Beirut, which Etel compared with San Francisco. The New York Times writes: “Her most widely acclaimed novel, Sitt Marie Rose, (1978) based on a true story, centers on a kidnapping during Lebanon’s civil war and is told from the perspective of the civilians enduring brutal political conflict. It has become a classic of war literature, translated into 10 languages and taught in American classrooms.”

As Simone and Etel drove me home to San Francisco one night after dinner in Sausalito, Etel asked me as we crossed the Golden Gate bridge to imagine how I would feel if San Francisco suffered such destruction. It was December, and she was bundled up in their Volvo like a Lebanese peasant (though she came from a wealthy family). Of the thousands of times I have crossed the Golden Gate bridge, I remember that time the best — stars over the Pacific, and the lights of San Francisco reflected in the bay. I always felt safe in San Francisco, a refuge from what is worst about America.

Today, the news is horrifying, and it’s getting worse. When we watched as the U.S. Capitol was attacked on January 6, we did not know that what we were seeing was an actual, organized, serious attempt at an authoritarian coup. New books have revealed much, but I expect the congressional hearings to reveal even more. The law is closing in on Trump’s enablers, and I have little doubt that Trump himself, and two or three of his children, will be indicted next year. At the very least, those indictments will be about financial crimes, and those crimes will be the easiest to prove. But, as Trump enablers such as Steve Bannon, Mark Meadows, and a bunch of right-wing lawyers face the choice between longer prison sentences and testifying against Trump, I expect them to testify against Trump, and I expect the evidence to be damning.

The rise of an organized authoritarian power structure is scary enough, but the gullibility of Americans is even scarier. Recent polls show that a majority of Americans may be willing to go right on voting for Republicans. We have no choice but to imagine the worst. If the Republican Party either steals or wins the national elections in 2024, then that will be the end of the American democracy and the end of the rule of law. Part of what I find I find incomprehensible about the politics and religion of America’s non-intelligentsia is that they imagine they would prosper under such a regime. No they wouldn’t. As soon as a right-wing authoritarian government was installed beyond the reach of democracy and the rule of law, ignorant Republican voters would feel the other end of the stick as the country’s wealth is transferred ever more quickly from the bottom to the top. A right-wing authoritarian government in the United States could never be stable. At least half of the population — largely those in the cities and on the coasts — would never put up with it. The Republican Party and its propaganda would ensure that there are brownshirts, scapegoats, and turmoil. Sham right-wing-run elections would never permit a democratic change of government. What alternative would be left other than civil war?

Already, authoritarian governments are working to escalate the turmoil. A story in the Times of London on November 13 reports that Britain’s most senior military officer has warned that the risk of an accidental war with Russia is now greater than at any time since the Cold War. There are increasing fears that Russia is preparing to invade Ukraine. British troops have been sent to the Polish border with Belarus because Belarus is trying to create a crisis by flying in migrants from the Middle East and sending them to the Polish border. Things such as this get little attention in the dysfunctional and not-very-smart American media.

I’ve tried to do some Googling to determine what has been written about intelligentsias in time of war. Most of what has been written is about Russia. But intelligentsias, at many times in many places, have seen and understood what others are slow to see and understand. It happened in Russia. It happened in Germany. It happened in Etel’s Lebanon. And now the United States could be well on its way. I’m afraid I was mistaken when I thought that this country was out of the woods when Trump left the White House. I still believe that Trump will go to prison. But that is not enough, as it has become increasingly clear that the Republican Party, post-Trump, will continue to try to establish a right-wing authoritarian government beyond the reach of law and fair elections. The details about their intentions grow ever uglier — for example, Michael Flynn’s remark about “one religion.”

In my Googling, I found this, written in 1972 by Richard Hamilton for Dissent magazine:

“In the world view of liberal intellectuals, those persons who share decent and humane values form a tiny minority standing on the edge of an abyss. In that world view they are always standing there, the problem being that there are so few people who share those values and so many potentially powerful and, if aroused, dangerous groups present in the society. The best one can hope for is that the threatening groups remain quiescent, that they not be aroused.

“The American liberal finds himself in a difficult world; he is sincere, concerned about the pressing problems in the society, willing to see changes made, but he also is trapped by the inexorable dictates of the situation. If these hostile groups were to be aroused (at one time the dangerous lower middle class was the problem, now there is also the dangerous white working class), the liberal minority would be unable to stem the reaction that would follow.”

As always, my disclaimer is that no one knows what is going to happen in the future. But my fear is this: If the American right wing succeeds in installing a Putin-style government, which is their clear intent, then there is a future in which this country is torn apart by civil war.