The flag on the back is the Christian flag, which is commonly flown in King, North Carolina. Also note the bumper stickers in the lower photo.

We could talk about why a surplus military vehicle belonging to the Pfafftown (North Carolina) militia, a right-wing paramilitary group, showed up at the polling place for the Nov. 7 municipal elections in King. We could talk about how, in the previous two elections in King, assault charges have been filed because of encounters between members of the conservative majority and the liberal minority. We could talk about how Republicans and churchgoers are upset because an atheist is running for the King town council. We could talk about how it’s part of my duty, as a local political operative, to be concerned about what happens at the polls on election days. But let’s don’t talk about any of that. I’m burned out on tomfool right-wing drama. Let’s talk about the truck instead.

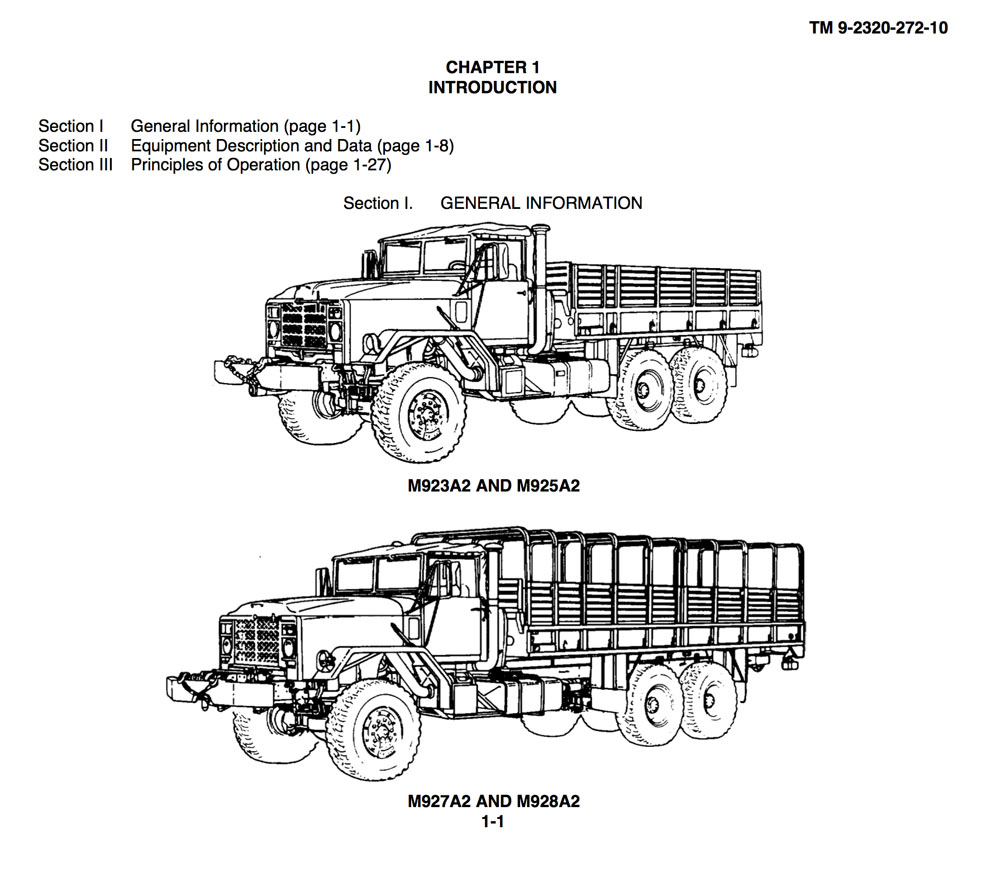

Because I’m a nerd with a Y chromosome, I find these trucks fascinating, just as cool machines. It happens that, only a couple of months ago, in writing book 3 of the Ursa Major series, I needed a truck like this for a fictional military operation. I had never seen such a truck, so I had to do some research on military vehicles. I never just make stuff up, when stuff must correspond to reality! I do whatever research is necessary. I found the army’s operator’s manual for the truck, which is 452 pages long. I admit without shame that it was fascinating reading, and that the truck almost becomes a character in the novel, the way Jake’s Jeep did in book 1, Fugue in Ursa Major.

I believe the truck in the photo is an M923A2 dropside cargo truck. These trucks come in about 30 different configurations, including dump trucks, wreckers, and vans. It has a Cummins diesel engine, all-wheel drive, and all sorts of cool features that harden it for military use. If you like fine machines (from aircraft to communications apparatus), you’ve got to love military specs.

The driver said he bought this truck for $10,000 a few years ago. I’m sure he drives it to church and to watch people vote. But I shudder to imagine where else.