Radio telescope, Arecibo, Puerto Rico

“We do not have to visit a madhouse to find disordered minds; our planet is the mental institution of the universe.”

— Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1749-1832

It is no big secret that, for years, the government has been paying academics to try to predict — and presumably prepare for — contact with intelligent life from outer space. Back in 1992, when I was in San Francisco, a friend from Boston was staying with me temporarily. One day his dad came to town unexpectedly. My friend’s dad was an economist, on the faculty at MIT. When my friend asked his dad what had brought him to San Francisco, his dad said that actually he was on his way down to Stanford for a government-sponsored meeting of academics from many fields. They were to brainstorm the consequences of encountering intelligent extraterrestrial life.

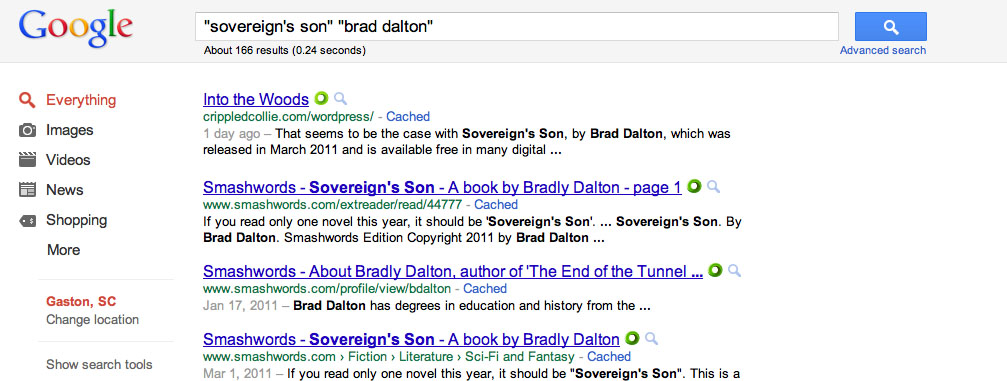

This week, another such study was released to the public, this one done mostly by Pennsylvania State University and NASA. You can download a PDF of this report at this link.

There was some mention of this report in the popular press, with the usual spin — silly photos of aliens, with stories focused on the most extreme scenario. Examples here.

The report divides its scenarios into three categories — beneficial contact, neutral contract, and harmful contact. In the category of harmful contact, the report describes a scenario in which extraterrestrials come to earth to destroy us because humans are so destructive. Humans must be prevented from destroying their own planet and from venturing out into space and destroying other planets. That’s the scenario that got all the attention in the popular press.

Since the early 1970s, I have been fascinated with the question of intelligent extraterrestrials and why they would come to earth. This is because I saw a UFO in 1972. No, this wasn’t just a blinky light in the sky, the kind of thing that leads to most UFO reports. This was much bigger and much clearer than that. I was with a friend. We both saw the same thing. This was in eastern North Carolina, around sunset but well before dark. We saw a huge object just over the treetops, less than 300 yards away. This object was as long as a football field and appeared to have the shape of a cigar-shaped tube. It was hovering, moving very slowly, and making no sound at all. There were no exterior lights, but there were what I might call portholes along the side, with interior light showing through the portholes. As we watched, the object made a kind of rotating maneuver just above the treetop level, and then it took off into the sky at an impossible, breathtaking speed, making no sound.

It was as though this object’s gravity was suddenly reversed and it fell into the sky, falling upward, accelerating at a geometric rate as it fell. Nothing built by humans could possibly accelerate like that. And it did it silently.

“Rational” types always say something like, “Oh surely you just saw Venus rising.” That is silly, because I did not see a small light in the sky. I saw a huge object, quite close. It would make just as much sense to say that that Boeing 747 parked and loading over there on the tarmac, its interior lights glowing through the windows, is Venus rising. I believe my own eyes.

I do, of course, recognize that, though what I saw is sufficient to convince me that we have extraterrestrial visitors, to everyone else it’s just another UFO report, proving nothing. But I am not on a mission to convince anyone of anything. I only long to understand what I saw, and what it means.

It amuses me that reports such as the one from Penn State and NASA have to say things like this:

“Humanity has not yet encountered or even detected any form of extraterrestrial intelligence (ETI), but our efforts to search for ETI (SETI) and to send messages to ETI (METI) remain in early stages. At this time we cannot rule out the possibility that one or more ETI exist in the Milky Way, nor can we dismiss the possibility that we may detect, communicate, or in other ways have contact with them in the future. Contact with ETI would be one of the most important events in the history of humanity, so the possibility of contact merits our ongoing attention, even if we believe the probability of contact to be low.”

They have to say, I guess, that we have not detected any form of extraterrestrial intelligence. But having seen what I saw, I skip past the question “Are they out there?” to “Why are they here?” Let’s do some reasoning. This reasoning won’t apply to those who have never seen a UFO and who have not seen what a UFO can do. I only claim that this reasoning is valid, then, for myself, because I have seen a UFO and am satisfied that, not only do they exist and possess stunning technology, they’ve been here for some time.

The question then is, why are they here? And what are they doing? Since it has been almost 40 years since I saw this UFO, I think I can safely rule out the possibility that they are here to cause harm. If they were here to cause harm, surely they would already have taken action. So two broad scenarios remain: They are here to be beneficial, or their presence is neutral. Since they have not revealed themselves (at least to the masses), it is possible that they never will. But it is also possible that they are following some kind of protocol to gradually make themselves known and to give the people of earth time to adjust to the biggest culture shock that mankind will ever know.

If I have seen a UFO, then it seems very likely to me that other people have seen them as well and that thus some UFO reports are true. If I and others have seen them, it seems reasonable to assume that governments know about them. I can only speculate about how many people in the government actually know what’s going on and why they keep it secret. Perhaps they are following a protocol, and perhaps the development of reports such as the Penn State / NASA report are part of that protocol, work that must be done on the earthling side to prepare the population.

Since there is intelligent life on earth, and since there is at least one intelligent species capable of traveling to earth, it seems reasonable that there are probably many intelligent species out there. If there are multiple civilizations, and if we have evidence that they have protocols for the induction of new planets such as earth, then it seems likely that there is some sort of galactic government. If there is a galactic government, then there are galactic laws, and earth is subject to those laws. I can just hear the libertarians moaning!

That, I think, is where we are. Earth, for decades, has been going through a process of being studied and prepared for induction into some kind of galactic federation.

Can it be legal under galactic law to destroy a planet’s ecosystem? I doubt it. Can it be legal under galactic law for earthlings to build spaceships and venture out into our own solar system and beyond and do whatever we please out there? I doubt it. It seems reasonable to suppose that, when a civilization attains a level of technology that permit it to violate galactic law — such as destroying planets, our own or someone else’s — then that civilization must be made aware of galactic law, and galactic law must be enforced. I am not by any means the first to imagine such a scenario. I am only doing my best to reason sensibly from a few facts that I am convinced are true.

Having thus reasoned, I am now going to speculate, to dream a little.

It amazes me that human beings have such different dreams. Some libertarians, for example, have a dream of a libertarian utopia. Peter Thiel, who founded PayPal, recently donated $1.25 million dollars to start developing artificial islands in the ocean where libertarians can have their utopia — with no minimum wage laws, no building codes, and all the weapons they want. I see this as sheer madness, a dream of a more primitive state in which poor excuses for human beings are free to exercise their predatory instincts without restraint. What further proof do we need that earth is the mental institution of the universe? Don’t like government? Don’t like laws? Here you are, then: Check out these new volumes of galactic law!

I have a different dream. That is that our incredibly ignorant, violent, backward species will, in my lifetime, get some sense knocked into it. We will learn to see our planet in perspective — a fragile oasis of life in a galaxy that is mostly empty, cold, and dark. We will learn that we can’t get away with exploitation — exploitation of our planet and the other life on it or exploitation of our own species. Ignorance and deceit will no longer succeed as a political strategy.

The power structures of earth will be turned upside down. Religions will be widely recognized as obsolete and tossed into the dustbin of history where they belong. Earth’s economy will be completely transformed — I can guarantee that that huge spaceship that I saw in 1972 was not burning fossil fuel. All the benighted political forces that want to drag us backward, to gain power and satisfy their greed by lies, by appealing to ignorance and to black-hearted religions, will be neutralized. To some people, it will be the worst thing they can imagine, the worst thing that ever happened. Their strategy for exploiting this planet, for increasing their power, for pursuing their greed, for spreading their ignorance, will be defeated, overnight.

That’s my dream. I hope I live to see it.