Once upon a time, when newspapers were both noble and strong, editors and publishers regarded readers’ time as very valuable. Editors and publishers understood that newspaper readers were trying to absorb as much information as possible in the least amount of time. They knew that most readers would not finish most stories. Readers would read until they had absorbed enough of a story to meet their needs, then they’d move on to another story, or move on with their day. Once upon a time, editors and publishers did not try to manipulate readers to rip off readers’ time and attention.

These days, many publications — especially on-line publications — actually withhold information and tease readers with information in order to extract more attention and more clicks. Headlines promise much more than the story contains. There are far fewer editors these days to advocate for the reader. The closer a publication is to the lower end of the business, the harder it tries to gain clicks and attention with the least possible information. Reading a newspaper used to be an efficient use of time. But reading on line is increasingly a kind of warfare, in which the reader has to fight with the publication to get at the information (and there may not be much information, no matter how many paragraphs you read).

One of my pet peeves is the anecdotal lede. Everybody writes them now, and there is no bigger time-waster in the world. A lede is the first paragraph of a story. Editors spell it lede because lead has a very different meaning in publishing, a meaning that goes back to the days of Linotypes. Anecdotal ledes, though, go back at least to the 1980s, when they suddenly became a fad with every newspaper reporter in the world. It was claimed — it still is claimed, actually — that anecdotal ledes “pull the reader into the story.”

No they don’t. They waste about five paragraphs of reader time and give reporters a chance to show off what bad writers they are. And who says we want to be pulled in, even if an anecdotal lede could trick us into that? I keep a collection of anecdotal ledes. Here are a few examples:

The New York Times:

• On a Sunday in early December, Marcus Brauchli, the executive editor of The Washington Post, summoned some of the newspaper’s most celebrated journalists to a lunch at his home, a red brick arts-and-crafts style in the suburb of Bethesda, Md.

Aren’t we just dying to know what was served?

I’m an alumnus of the Winston-Salem Journal and have watched that once-great local newspaper, which once won a Pulitzer, shrivel into oblivion. My collection of bad ledes from that newspaper is particularly large, because they never would have gotten past the copy desk when I was there.

The Winston-Salem Journal:

• John Barr is sipping a cup of coffee in the kitchen as his wife, Alysse, finishes up the baths of their three children, Ty, 5; Hunter, 3; and Gionni, 1.

Wow. It was almost like being there.

• Hello Kitty was popular. So was soccer. Hannah Montana was there, but only slightly more common than a hammerhead shark fighting a swordfish.

Sounds like my high school, too.

• Elizabeth Nesmith couldn’t talk or eat Sunday afternoon.

Me neither.

• As the sky over Washington Park turned hazy Friday night, Joe Tappe strolled down the sidewalk from his house at Gloria and Park avenues, crunching over fallen leaves and carrying a plate of dip.

By the fourth paragraph, maybe we’ll know where he was going.

Der Spiegel:

• The blades of the wind turbine are made of plain wood painted red, and they measure exactly 1.2 meters (3.9 feet) long. Their curved edges are only roughly sanded.

I am so pulled into the turbine!

When I encounter anecdotal ledes, I skip immediately to the fifth paragraph to see if the story begins there. If it doesn’t, I move on. When I was at the San Francisco Examiner and the San Francisco Chronicle, whenever we had the perennial debate about why we were losing readers, I’d always say that it was because the anecdotal ledes were driving readers away.

It’s not uncommon these days, in on-line publications and even in Washington Post op-eds, to see the lede withheld until the very last paragraph. That is nothing less than abuse of the reader.

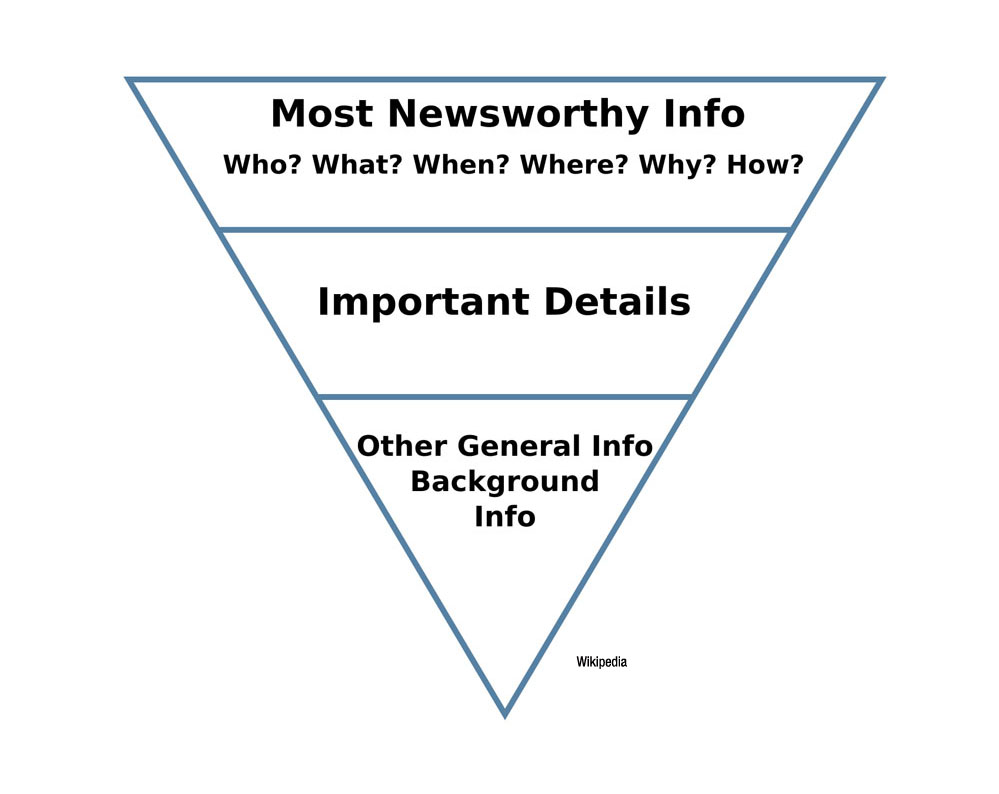

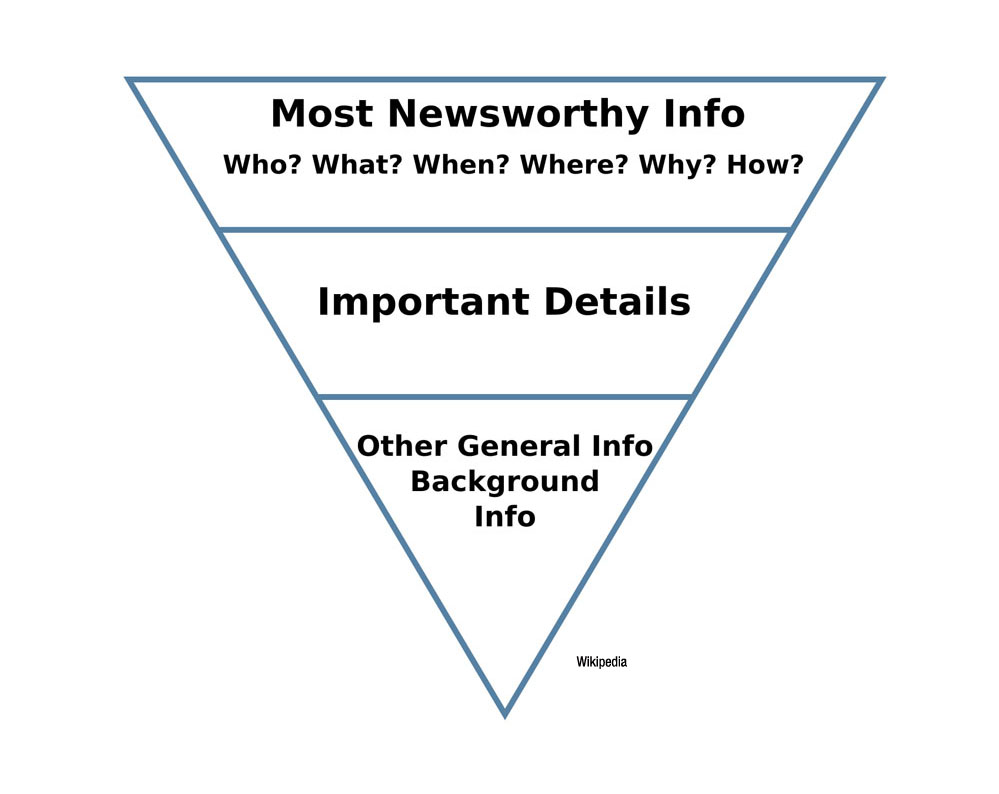

Maybe I’m hopelessly old-fashioned, but, as I see it, readers have rights. One of those rights, when reading for news, is the right to the inverted pyramid. But I’m just a voice in the wilderness, in a time when we need the inverted pyramid more than ever. I don’t have a clue what to do about it, other than not to give our attention to those who abuse it.