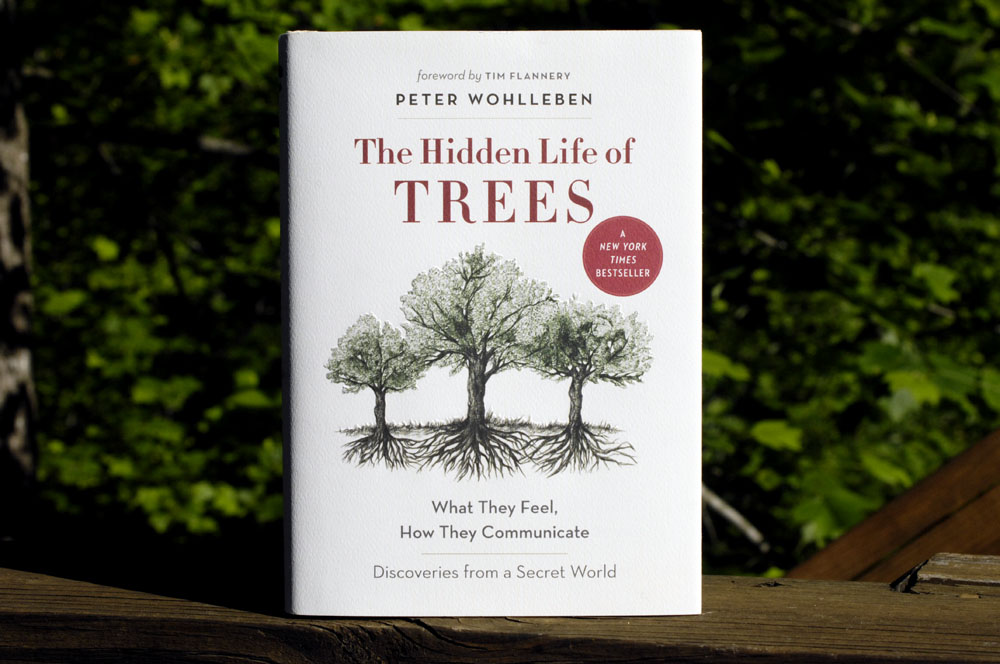

The old translation and the new

Plato: The Complete Works. Edited by John M. Cooper, Hackett Publishing, 1997. 1838 pages.

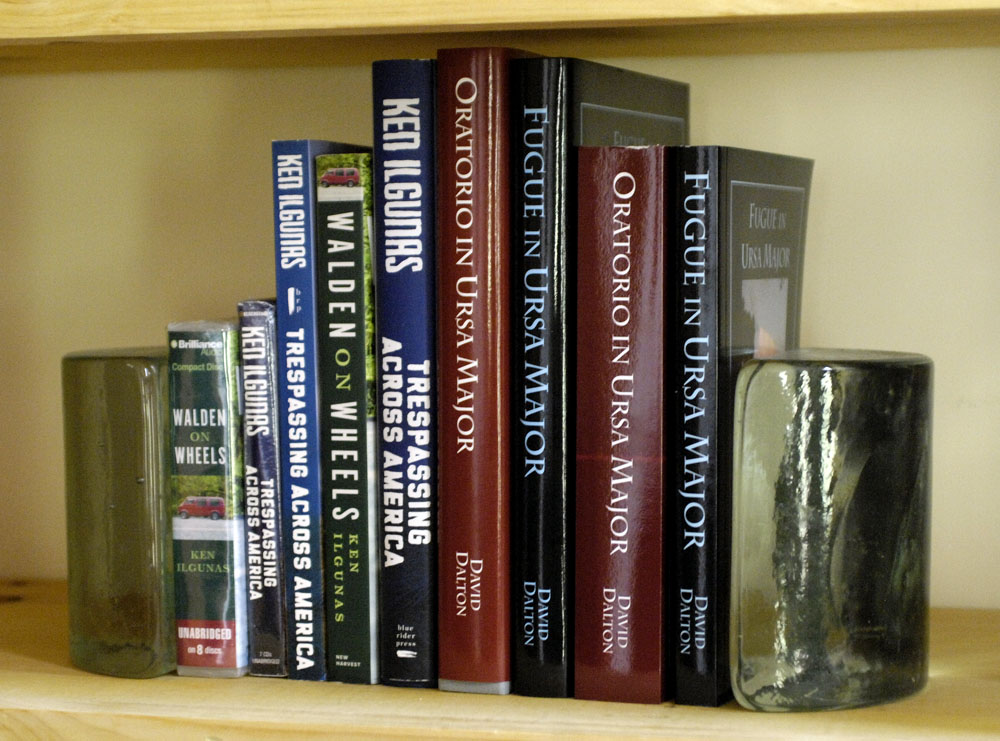

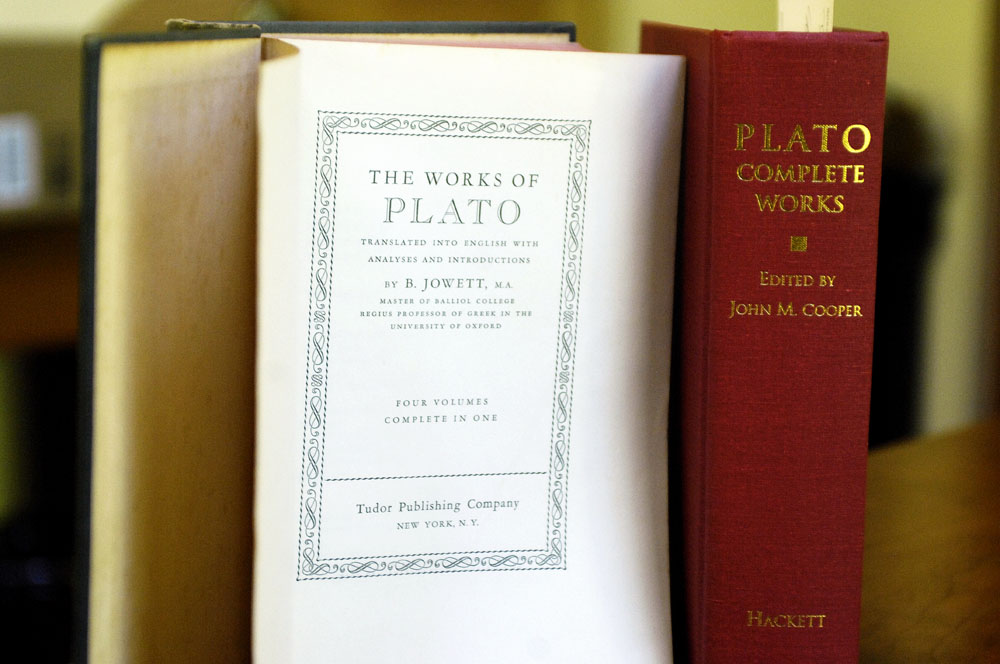

For years, my only volume of Plato was the translation by Benjamin Jowett, first published in 1871. I bought the volume in a used bookstore. It seemed like a good find at the time. From the pencil markings in the front, it appears that I paid $12 for it. Most of my previous reading of Plato was from the Jowett translation. The Phaedrus dialogue, in particular, figures into my Ursa Major novels. One of my two main characters even is named Phaedrus.

Now I know that relying on such an old translation was a huge mistake. An academic friend happened to mention a couple of months ago that the Jowett translation is badly bowdlerized. Instead of Jowett, we now have a new and far superior translation, published in 1997. It’s edited by John Cooper, and it isn’t bowdlerized. It also isn’t cheap. The hardback will cost you over $50.

Benjamin Jowett, by all accounts, was a heck of a scholar. He was at Oxford. But he also was a theologian and a 19th Century evangelical. Do you hear the alarm bells going off? It means that Jowett can’t be trusted not to censor the Greeks. I’ve not spent that much time on side-by-side comparisons of the translations, but it was easy enough to see that where Jowett used the English word “love,” the Cooper translators used the word “sex.” Now that’s a very different thing, isn’t it? And one of the areas in which we most don’t want to misunderstand the Greeks is on the distinction between love and sex. Sex is discussed quite a bit in the Plato dialogues. It’s discussed very casually and without the slightest sign of the squeamishness that is detectable in the Victorian translation. Jowett’s theology prevented him from understanding this. I sometimes wonder how Greek literature even survived the long, dark Christian era. My guess is that it’s only because Christianity required the fetishization of Rome, and along with Rome, Greece. We’re lucky that the squeamish made do with mere bowdlerization, though I have little doubt that some lost texts were lost because it was thought best to copy over something so un-Christian.

There’s another, more subtle, difference in the translations. That is that, in an archaic translation, Plato himself seems archaic. But, in a modern translation, Socrates and his young men seem thoroughly modern. Their wonderful sense of humor seems just the same as ours. Human foibles, it would seem, haven’t changed a bit. And so, reading Plato in a modern translation makes us realize that the distance between (ahem) us smart folk and the Greeks is about a millisecond. They were just like us in a great many ways, and that’s incredibly endearing. There is nothing at all formal about the dialogues. They’re super-casual, just the guys sitting around talking, jesting, and trying their wits against each other. You realize that Socrates was popular not just because he was smart, but also because he was funny, always kind (even to the gym rats with their modest intellects), and fun to be around.

So, as a smart folk and as a reader of this blog, you do keep a volume of Plato by your bed for fill-in reading, don’t you? If you have the Jowett translation, slip a card into it with a warning to the next owner about bowdlerization, sell it to a used bookstore, and get yourself the new Cooper translation.

Don’t fret too much over the The Republic. Utopias as a form of literature are interesting, but their shelf life is terrible. Instead, browse the other dialogues according to your mood.

If you’re new to Plato, I would offer a warning. It’s sometimes difficult to tell when Socrates is being serious. He sometimes elaborates on arguments that he doesn’t believe, at all. This is certainly true in The Phaedrus. If we were sitting at Socrates’ feet, no doubt he’d wink at us from time to time, and he’d sometimes be interrupted by laughter that isn’t mentioned in the dialogues. It’s like listening to Mozart. Frequently Mozart wants you to laugh at his music, just as Socrates wants you to laugh at some arguments. So one needs to be very careful about taking snippets of Plato out of context. It’s possible to get him exactly backwards.

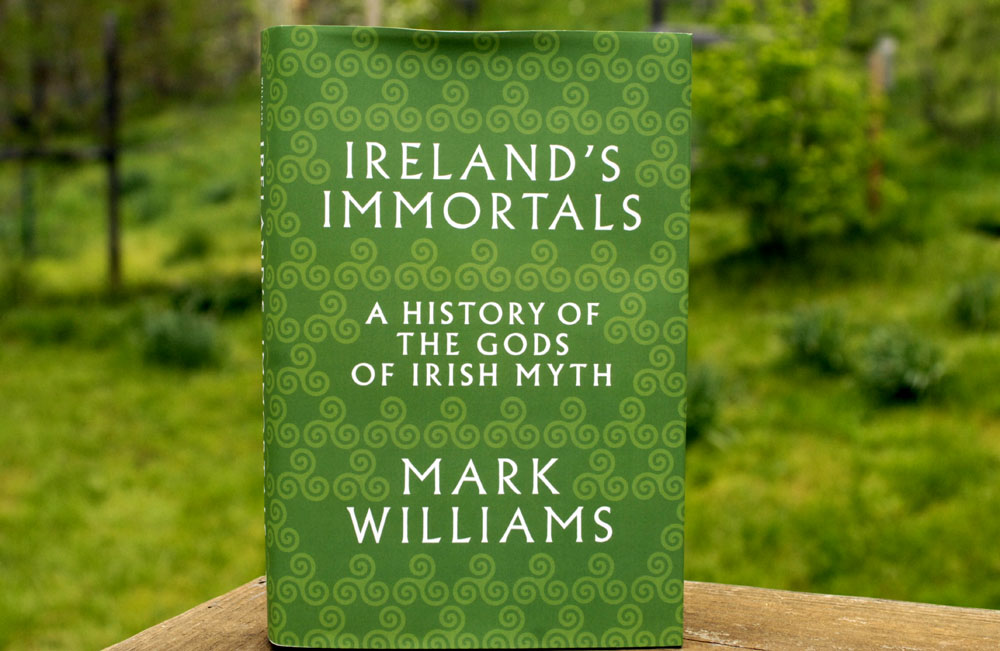

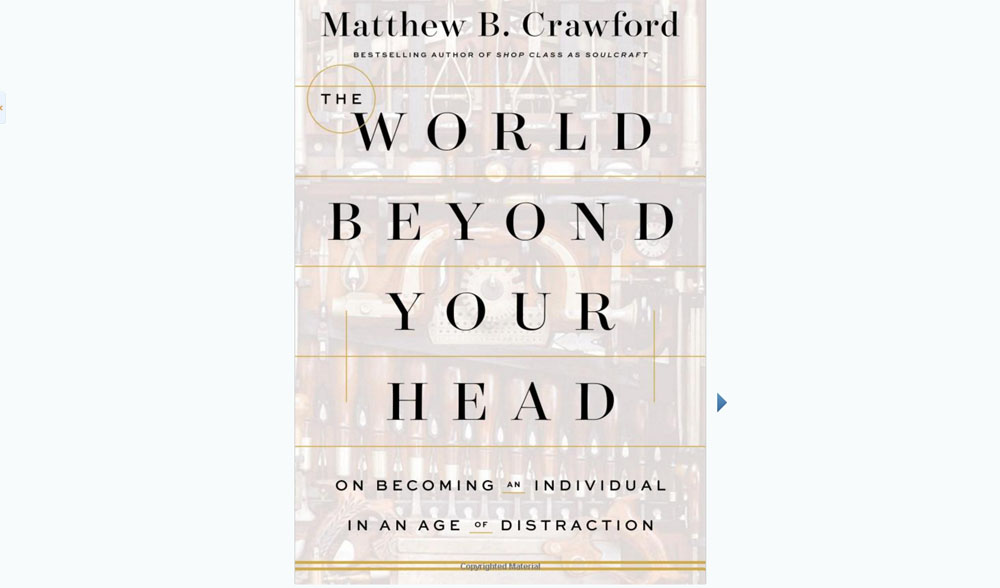

The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming an Individual in an Age of Distraction. By Matthew B. Crawford, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016. 320 pages.

This is a strange book, difficult to review. I’d call it philosophy, but Crawford says that it’s more a polemic. The author wants you to take control of your own attention instead of allowing your attention to be dominated by the many forces that have such clever ways of usurping your attention for their own purposes. The author also wants you to be less abstract, less concerned with representations of the world (the most extreme of which would be virtual reality) and more concerned with the world right under your nose.

Crawford’s philosophical position naturally leads him to a great respect for skilled practice, both for the way it requires our attention and the way it requires us to pay attention to the real world, the world outside our heads. He mentions many skills — cooking, gardening, motorcycle riding, pretty much anything that requires the use of tools. He talks about how quickly you can get killed if your attention lapses while racing a motorcycle. He detests “drive by wire” automobile engineering, in which the brake pedal isn’t truly connected to the brakes, or the steering wheel barely connected to the steering. This, by the way, made me appreciate once again how much I like the honest Mercedes engineering of my Smart car, in which the driver is truly connected to the road. It helped me realize how good design — for example the design of my Nikon professional cameras — makes the camera feel like a natural extension of the body and the body’s visual system.

Having made his case in the first part of the book, he devotes his last chapter to the art of organ building, as an illustration of his message. As an organist, I found this fascinating. If Crawford himself is a musician, he didn’t say so. But the work and time that he put into understanding the craft of organ building made me realize that he is almost certainly equally diligent about whatever else commands his attention.

I’m appending a couple of paragraphs about the organ, not because it summarizes the book but because it’s funny, and it’s a great piece of writing.

“Pipe organs are to the Baroque era what the Apollo moon rockets were to the 1960s: enormously complex machines that focused the gaze of a people upward. Pushing the envelope of the engineering arts, a finished organ stood as a monument of knowledge and cooperation. Installed in the spiritual center of a town, a pipe organ mimics the human voice on a more powerful scale, and summons a congregation to join their voices to it. The point is to praise something glorious that transcends man’s making. Yet the congregants can’t help but notice that this music of praise, like the instrument that carries it aloft, is itself glorious.

“A big pipe organ thus expresses both humble piety and vaunting pride at once. It can be shockingly indiscreet in this later role; the organ often dwarfs the ostensible altar. But perhaps these tendencies get blurred together in the life of a congregation. When the choir is at full song, the stained glass is rattling loose, and the whole house seems ready to launch, what then? Then the organist pulls out all the stops. He shifts his weight to the right. His left foot is poised over the leftmost pedal, the low C, and now he stomps it, sending a thousand cubic feet of air per minute through massive pipes to blast heaven’s favorite pigeons out of the rafters. Now the very pews transmit joy to women’s loins, and the strongest man in the congregation feels himself reduced to a blushing bride of Christ. Now one feels it is God’s own organ that fills the sacred chamber, and when this happens, praise comes naturally: hallelujah!”