Fashion, Faith, and Fantasy in the New Physics of the Universe, by Roger Penrose, Princeton University Press, 2016, 502 pages.

Into the Cool: Energy Flow, Thermodynamics, and Life, by Eric D. Schneider and Dorion Sagan, The University of Chicago Press, 2005, 362 pages.

What Is Life? by Erwin Schrödinger, Cambridge University Press, 18th printing 2016.

Most of Roger Penrose’s Fashion, Faith, and Fantasy is over my head. But, as always with Penrose, I absorb what I can. Penrose ought to be a rock star as a physicist and mathematician. In some circles, he is. I think he’s the Einstein of our age.

But, tough reading though it is, and though it’s not the primary concern of this book, there is one concept in this book that is increasingly clear to me. It’s something that has puzzled me for years. Here is an uncomplicated way to think about the question. Why is it that fresh-squeezed orange juice is such a potent medicine and health-builder, but reconstituted orange juice is not much better for you than soda pop or any other sweet drink?

The answer, I believe, has to do with entropy.

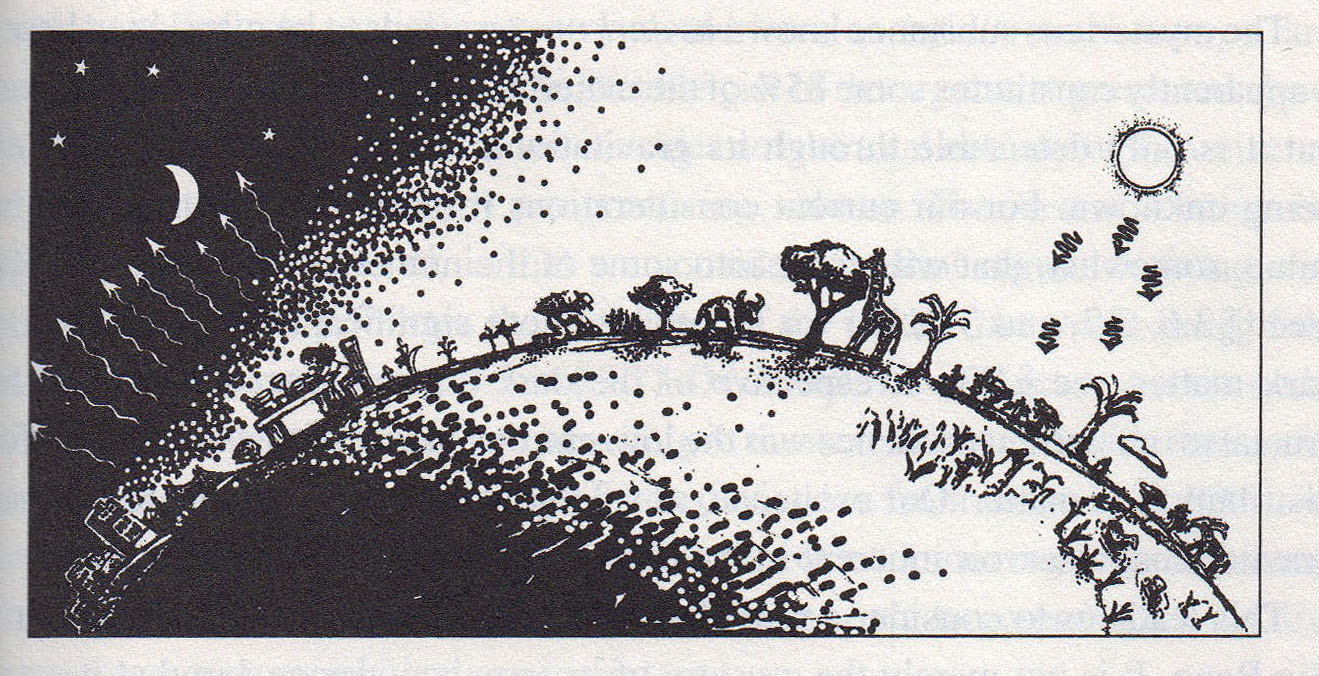

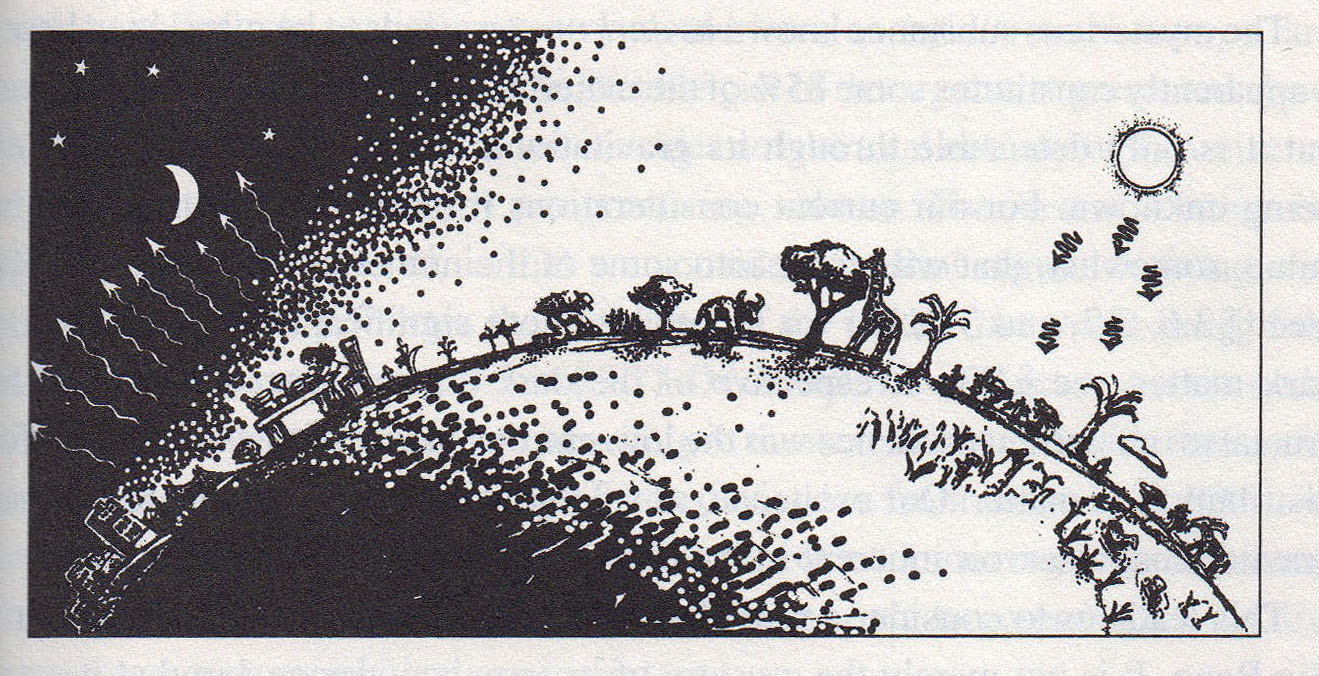

Penrose’s book contains this illustration (I believe it was drawn by Penrose himself). I’ve also quoted the text that appears with the drawing:

Figure 3-16: Life on Earth is maintained by the great temperature imbalance in our sky. Incoming low-entropy energy from the Sun, in relatively fewer higher-frequency (~yellow) incoming photons, is converted by the green plants to far more numerous lower-frequency outgoing photons, removing an equal energy from the Earth in high-entropy form. By this means, plants, and thence other terrestrial life, can build up and maintain their structure.

What is entropy? Entropy is a lack of order. The concept of entropy has everything to do with the second law of thermodynamics, which says that the total entropy (or disorder) of an isolated system always increases over time.

As a living organism, your body is in a highly ordered state. Without a mechanism for ingesting order and eliminating disorder, your body would decompose, and you would die. Your source of the order you ingest is in your food.

Walk into a grocery store. Do you see any food that could have been produced without the sun? Of course not. All food contains negative entropy — that is, order. And the source of that order is the sun. It’s not just the energy of the sun that matters. It’s the fact that the sun is a very hot spot in a cold sky. All life on earth depends on that hot spot in the cold sky. This huge thermodynamic imbalance, or gradient, allows life to create order and avoid entropy.

Penrose again:

By Planck’s E = hv (see §2.2), the incoming [photons] are individually of much higher energy than those returning to space, so there must be many fewer coming into the Earth than going out for the balance to be achieved (see figure 3-16). Fewer photons coming in mean fewer degrees of freedom for the incoming energy and more for the outgoing energy, and therefore (by Boltzmann’s S = k log V) the photons coming in have much lower entropy than those going out. The green plants take advantage of this and use the low-entropy incoming energy to build up their substance, while emitting high-entropy energy [for example, body heat]. We take advantage of the low-entropy energy in the plants, to keep our own entropy down, as we eat plants, or as we eat animals that eat plants. By this means, life on Earth can survive and flourish. (These points were apparently first clearly made by Erwin Schrödinger in his groundbreaking 1967 book, What Is Life?)

Think of it this way:

Question: Why are fresh foods healthier than un-fresh foods, or foods that have been preserved? Answer: Because the fresh foods have the maximum amount of negative entropy from the sun, since plants begin to decompose the moment they’re harvested.

Question: Could we eat compost and other rotten stuff to stay alive and healthy, since compost contains all the nutrients we need? Answer: Probably not, because decomposition has reduced the compost to a disordered, high-entropy state. Simple organisms, of course, can live on compost. Earthworms can live on soil only because they’re very efficient at extracting negative entropy from high-entropy food. They can eat their body weight each day. We humans require food with much lower entropy.

I’ll leave you to think about these concepts, but I think it’s clear how this concept applies to nutrition and health. A healthy diet is about much more than just getting the right vitamins, minerals, proteins, etc. It’s also about getting all those nutrients in the most ordered state possible, as close to the sun as possible. Processed foods are unhealthy not just because they contain a lot of salt, fat, and chemicals. They’re unhealthy also because the processing decomposes the ingredients. If we don’t take in enough negative entropy, some part of our body will surely become disordered beyond the body’s ability to fix it, and we get sick.

The concept of entropy sheds new light on the wisdom of Michael Pollan’s simple rule for eating: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants. Avoid edible food-like substances.” Those edible food-like substances, in every case, are substances that formerly were food but which were rendered disordered and high-entropy by processing.

Another way of boiling down the concept might be: Choose foods that are as close to the sun as possible, and keep cooking and processing to a minimum to maintain the food’s molecular order.