Oyster soup, more or less Louisiana style. The sandwich is a winter-style BLT — lettuce from the garden, but no tomato.

Oysters are magical somehow. They’re also slightly creepy. Picky eater that I was as a kid, it’s surprising that I even liked them. But I did, either batter-fried or in a creamy stew. We had them fairly often, as I recall.

In these parts, in the Appalachian foothills and the North Carolina Piedmont, oysters are harder to find than they used to be. People don’t want to shuck them (or don’t know how). And though they’re available by the pint already shucked, I don’t think many people buy them. Rather, when people in these parts eat oysters, it’s almost always in the restaurants that I call fried fish houses.

A neighbor gave me these oysters. He had bought an entire bushel of fresh oysters. A grocery store at Belews Creek regularly has them shipped in by the lorry load, either from the Chesapeake Bay or Florida. As far as I could tell from looking at the box, these came from Florida. The cost was shockingly low — $30 for the bushel of oysters, shipped on ice overnight. My neighbor said that the store sold the entire lorry load an hour after opening in the morning. Somebody knows what to do with them, especially at that price.

It had been 25 years since I’d shucked oysters. That was on vacation near Point Reyes north of San Francisco, back in my moneymaking days. There are two oyster farms there — the Hog Island Oyster Company, and the Tomales Bay Oyster Company. I still have my oyster knife, unused for those 25 years. Opening oysters is rather dangerous work, though I’m sure it gets safer with practice. Today I wore glasses and heavy gloves.

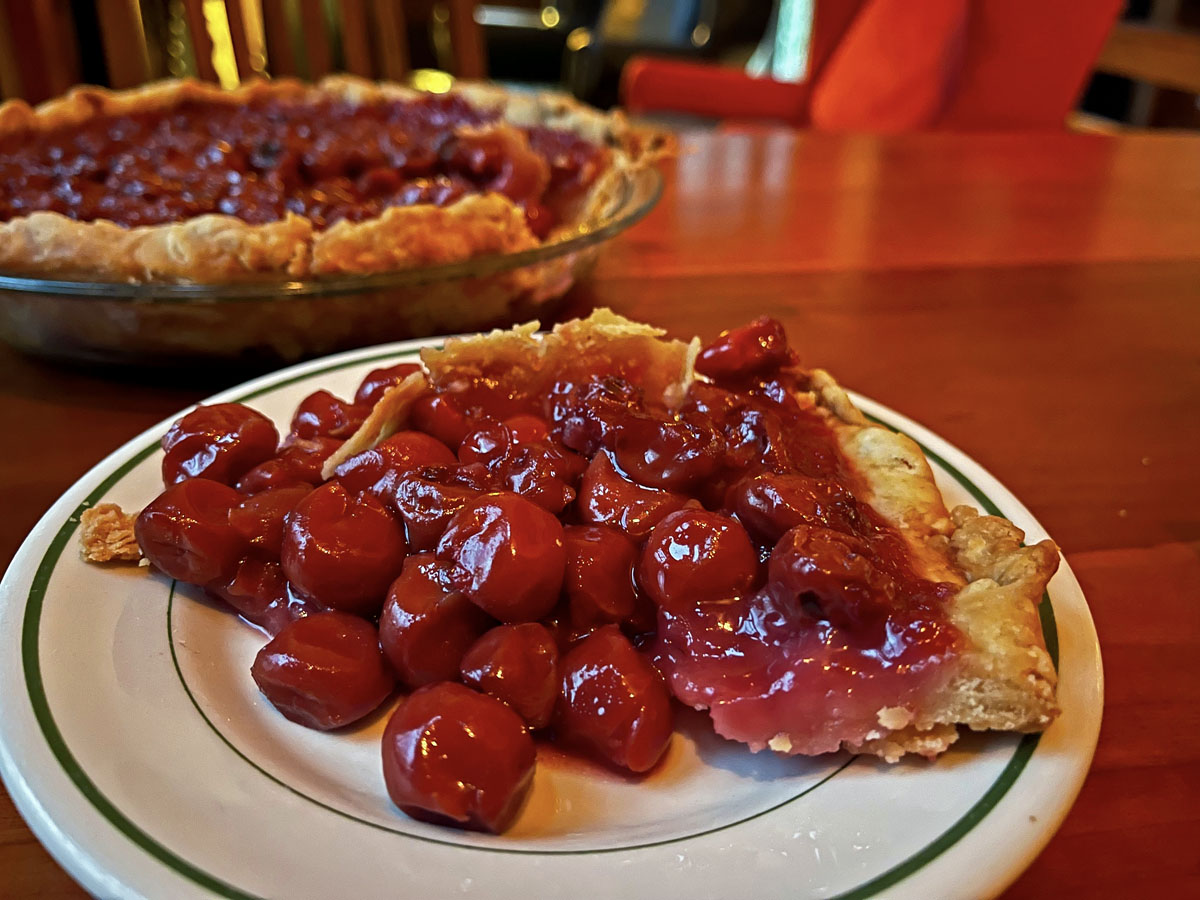

I had at first planned to make a creamy oyster stew. But I decided instead to make something healthier and a bit lower in calories, inspired by a recipe in the Washington Post for a Louisiana-style oyster soup. I used fresh mustard greens from the garden, tomatoes that I grew and canned, and lots of garlic.

With hundreds of thousands of miles of earth’s coastlines to work with, oysters grow (and are eaten) all over the world, though they are not of the same species or variety. I Googled to see if I could find an oyster cookbook with recipes from all over the world. I could not find such a cookbook. On a trip to Scotland in 2018, I sampled one of Edinburgh’s famous oyster bars. It was interesting, and very pricey. It also was rather city-fied. The world, I think, is waiting for someone to make a global oyster tour and write a cookbook on provincial oyster-eating, worldwide.

The neighbor’s bushel of oysters.