Rocking chair rehab

I apologize for going so long without posting. I’ll blame it on the weather — first freezing cold, with some water problems, followed by heavy rain. January has been dreary so far.

But today was fairly nice, and Ken got started on a project that I’m happy to see come up in the queue: the rehabilitation of the rocking chairs. I bought the chairs as a gift for my mother some years ago, and she gave them back to me when I moved back to North Carolina. The chairs are classics, made by the P & P Chair Company, the original maker of the Kennedy Rocking Chair. You can still buy these chairs, and they’re very pricey. Mine have been sitting on the side porch for five years, and the weathering had taken its toll.

I did not like the original finish on these chairs. It was that plastic-skin finish that everything seems to have these days. The finish does not soak into the wood, and over time it peels off in tiny flakes, leaving the wood unprotected.

Ken’s first step was to sand the chairs. That left the chairs with a silvery-gray patina that is quite beautiful. The next step will be to apply a new finish. We’ve chosen a deck stain, because it’s the kind of finish that goes on thin and soaks into the wood. And of course it’s a finish designed for protecting wood that is exposed to the weather. I’m hoping that it will protect the chairs better than the original finish.

And whose knows. After the finish is dry, the chairs may come indoors and sit by the fireplace for the rest of the winter. Life is hard for porch chairs.

In the photos below, the new finish has not yet been applied.

Rainfall for 2013: 69.2 inches

The abbey has a new rain gauge accurate to 1/100th of an inch

Some parts of North Carolina have set records for rainfall this year. Acorn Abbey’s gauge has recorded 69.2 inches.

The breakdown by month:

January: 10.15

February: 3.8

March: 3.75

April: 5.4

May: 5.1

June: 8.9

July: 11.825

August: 5.85

September: 1.7

October: 1.35

November: 4.875

December: 6.6

The normal rainfall here is about 44 inches per year, so this has been an exceptional year. I’m thinking that a pattern is emerging for this area — that in years in which La Niña is not active, rainfall is generous and may well be trending upward, as is predicted in most models of climate change for this area. In La Niña years — curse La Niña! — all bets are off. La Niña summers have been wretchedly hot and dry.

The winter rye in the garden got a poor start because September and October were unusually dry. But it’s coming along and should make the chickens very happy this winter.

Christmas in Danbury

New leak tells us what we already knew: Google is evil

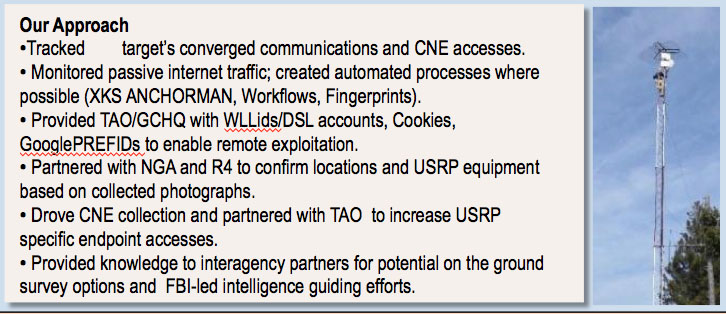

From an NSA presentation leaked by Edward Snowden

Bloggers at the Washington Post have reported on an important new leak by Edward Snowden. This one reveals that the National Security Agency uses Google cookies to identify and target computers on the Internet. This should surprise no one, but we need all the information we can get on how elites snoop on us.

What the leak reveals is that the NSA uses Google’s PREFID cookies to identify and track computers on the Internet. So what is a PREFID cookie and how does it work?

When you sign in to any Google service (such as Google mail), Google knows who you are. They assign your browser a PREFID cookie. This cookie reveals your identity to any site on the Internet that references the cookie and wants to track you. This tracking is not anonymous. Google knows who you are, and there is nothing to stop them from sharing your information.

How much does Google know about you? What did you tell them when you signed up for Google mail? You probably also gave them your cell phone number, right? In addition to the personal information you’ve given Google when you filled out their sign-up forms, Google has tracked you and captured and stored your Internet browsing history, which they have mapped to your real name and real identity. The Snowden leak does not reveal whether Google shares its identifying information with the NSA, but we’d be fools not to assume that they do.

It shocks me sometimes how revelations like this don’t disturb a lot of people. I think the assumption is that, because they’re doing nothing wrong or illegal, all this tracking doesn’t matter. But remember, this information is saved in Google’s (and the NSA’s) vast databases. Like a credit history, it will be used against you for years, perhaps for your entire life. When this secret information about you is sold or shared, you won’t know about it. Unlike credit histories, there are no laws that permit you to know what information about you is kept in these databases or that would permit you to challenge errors. There is nothing from stopping a company like Google from selling this information about you to anyone who wants it — a potential employer, for example, or to private investigators. If you’re ever involved in a lawsuit or a legal scrape, you can be sure that they’ll check your Internet history.

So what can you do? Don’t use Google mail! Don’t use Yahoo mail either. If you insist on using any of Google’s or Yahoo’s services that require you to sign in, then don’t stay signed in, and work out a means of keeping your cookies cleared. One solution, if you insist on using Google mail, would be to have two browsers on your computer. Use Firefox, say, for email only. Use a second browser, Chrome maybe, for all your browsing, and don’t sign in anywhere in this browser. Load up Chrome with all the essential privacy extensions — Ghostery, DoNotTrackMe, Flashblock, Referer Control, Facebook Disconnect, AdBlock, etc. Yes, some of these extensions will make your browser less convenient, but that’s the cost of greater privacy and security.

It’s ironic that Google Chrome, as far as I can determine at present, can be configured as the most secure browser. This is not a Google virtue, it’s that there are a lot of good privacy extensions available for Chrome. Here’s a DuckDuckGo link to get you started.

Vole control: the fire

A vole flees the fire in the wildflower patch.

There were two voles hiding under the brush pile when Ken lit it on fire. As soon as they perceived what was going on, they ran to another brush pile a few feet away that was waiting to be burned.

“Poor things,” said Ken. But we burned the brush in the wildflower patches anyway. The voles fled toward the garden when the last brush pile was thrown onto the fire. I would have preferred that they’d gone to the woods.

Vole control

Ken said that, when he was pulling up dead stalks from one of the wildflower patches yesterday, a vole sat and looked at him for a while, as though to say, “What are you doing to my neighborhood?”

Of all the many little creatures that live around (and off of) the abbey, the voles are the least welcome. They do a lot of damage in the garden. Their population can jump incredibly fast if the livin’ is easy. They’re verminy, though they’re also cute in a mousy sort of way. Their other name is “meadow mouse.” But somehow calling them by the more charming name of meadow mouse would make it harder to destroy their neighborhoods.

It was an extremely wet summer, which meant a lot of brush growth. The voles love that, because it provides them with cover. Ken has been clearing the area around the garden, and the voles don’t like it at all. You can trace their runways from the chicken house to the pump house, from the garden to the wildflower patches, from the wildflower patches to the grove of trees in front of the house, and from the grove to the day lily patch. They’re furtive little things, and though we see them often they’re hard to photograph.

As far as I’m concerned, they can make themselves a new runway from the garden all the way back to the rabbit thicket and the woods, where they’d be welcome if they’d stay there. I just hope that no one ever writes a Watership Down that’s about voles rather than rabbits. That would make it much more difficult to burn out their neighborhoods and turn them into little refugees.

The voles are not happy about this. It will be burned.

It was a warm day, so Lily watched the proceedings from an open window.

Keeping an eye on the FCC

President Roosevelt prepares for a fireside chat.

A couple of days ago, I posted an item on the importance of keeping an eye on the FCC. The item was focused on the future of over-the-air television, which may not affect your world very much. Still, we all need to keep an eye on the FCC, because decisions made by the FCC are critical to the future of the media, the future of the Internet, the choices we have, and what we pay.

A friend of mine who teaches communications law commented on that post. So that his information doesn’t get lost in a comment, I’m reposting it here.

The libertarians’ absolutist argument against regulation in the communications sector is silly on three particularly ironic points:

1) We already have a largely unregulated system thanks to the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which loosened or erased many longstanding rules, particularly those guarding against monopoly ownership. Among other things, the Act led to an almost overnight consolidation of the radio industry whereby a company like Clear Channel could grow from 60 to 1,200 stations in 18 months. The first order of business in that nationwide takeover was the elimination or decimation of local news staffing at all of those stations.

2) The media and telecom giants, from Time-Warner Cable to Disney, long ago captured the regulatory agencies, along with Congress and state legislatures, and openly and brazenly manipulate the rules they are supposed to live by. Furthermore, the FCC often doesn’t even enforce its own rules, making them meaningless. Just one example here: The FCC has allowed Rupert Murdoch to get around the newspaper-broadcast cross-ownership ban by granting him a waiver year after year; thus, he can control newspapers, television stations and radio stations all in the same market (New York, for one).

3) Media companies WANT there to be rules because the rules help them operate in a necessarily structured and predictable environment, and because, more often than not these days, the rules favor their interests against those of the public. The ban on municipal broadband in North Carolina is a prime example, but industry-friendly — indeed, industry-written — rules stretch to the FCC and the Justice Department, which, for example, is sure to rubber-stamp a merger between Comcast and Time-Warner Cable if the two companies decide to go ahead with it. It would create a monopoly that would control the television and Internet services of about 50 percent of the American population.

There are other reasons that the libertarian dream of a no-rules-at-all utopia is stupid, but those three suffice. I suppose the fundamental point to make is that their position is ahistorical. It is detached from both the technical and legal history of the communications sector. When the federal government first started regulating radio in 1927, it was because the radio owners themselves were screaming FOR regulation — someone to police the wild, wild west of their new industry and sort out the chaos of too many stations chasing too few frequencies. Regulating the technical aspects of radio was at the center of the FCC’s mandate when it was created by the Communications Act of 1934, and it remains a vital part of the agency’s mission today.

An example particular to Acorn Abbey: The only way there will ever be high-speed Internet service in such a rural locale will be through the use of so-called “super wifi,” which harnesses unused “white space” on the “gold-plated spectrum” that television stations enjoy. It can travel for miles and penetrate buildings just like a TV signal. There are even experiments under way to see if television transmitters can be altered so that they also can transmit Internet traffic. It would solve the rural broadband build-out problem overnight because the infrastructure is already in place.

Of course, the same companies that routinely decry regulation of any kind, the likes of Comcast and Time-Warner, will do anything they can to manipulate the rules to prevent the above scenario from happening. And they will try to manipulate the rules at the federal, state and county levels to stop any new efforts to break their monopoly control. And once again, the problem will not be that we have regulations. The problem will be that we have regulations written to benefit the regulated, not us.

For background on the Radio Act of 1927:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radio_Act_of_1927#The_Radio_Act_of_1927

For background on the Communication Act of 1934:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Communications_act_of_1934

For background on the Telecommunications Act of 1996:

Sousveillance?

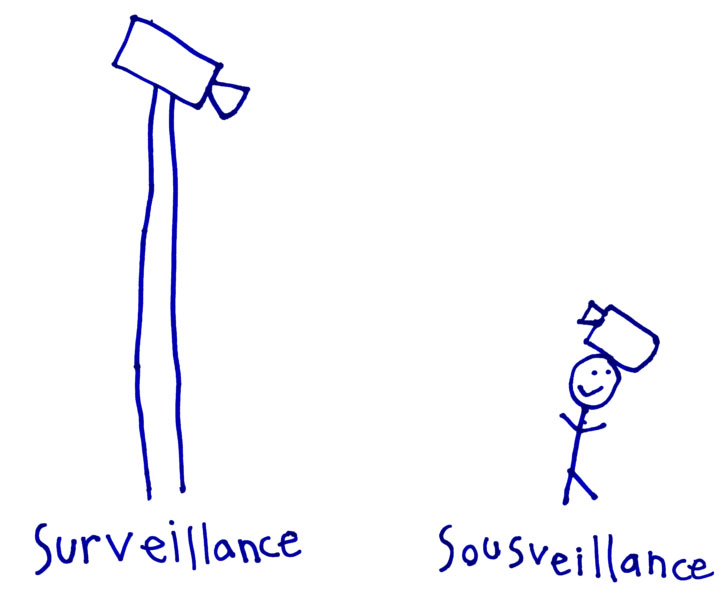

Source: Stephanie Mann, age 6, via Wikipedia

Periodically I check out the web site of David Brin, a science fiction writer and futurist, to see what’s on his mind. Brin is the author of the brilliant and classic Startide Rising (1983), which won both the Nebula and Hugo awards the year it was published. But, smart as Brin is, I find that I usually disagree with him. This is because I put him in the unpleasant category of techno-utopians — people who think that technology will solve all our problems, including our energy problems and even our political problems. I think that is bunk, and dangerous bunk.

Brin had linked to a piece he wrote in “The European” in which he argues that the solution to growing surveillance and invasion of privacy is “sousveillance.” The word “sousveillance” is a made-up word and is the opposite of surveillance. It means spying up at elites the same way they spy down on us. The prefix “sur” of course comes from a French word meaning over, or above; and “sous” is another French word meaning under, or beneath.

This notion that sousveillance is an effective antidote to surveillance seems to me to be so obviously silly that I’m inclined to think that the techno-utopians are even more deluded than I had thought. Just give everyone a Google glass and we’ll fix the world’s surveillance problem!

First of all, there is a straw man fallacy: “… [F]or the illusory fantasy of absolute privacy has to come to an end.” Who said anything about absolute privacy? There has never been such a thing as absolute privacy in American society or American law. The law and the Constitution are almost silent on the issue of privacy. But there have been lots of lawsuits having to do with privacy, and as far as the courts are concerned the issue is pretty settled.

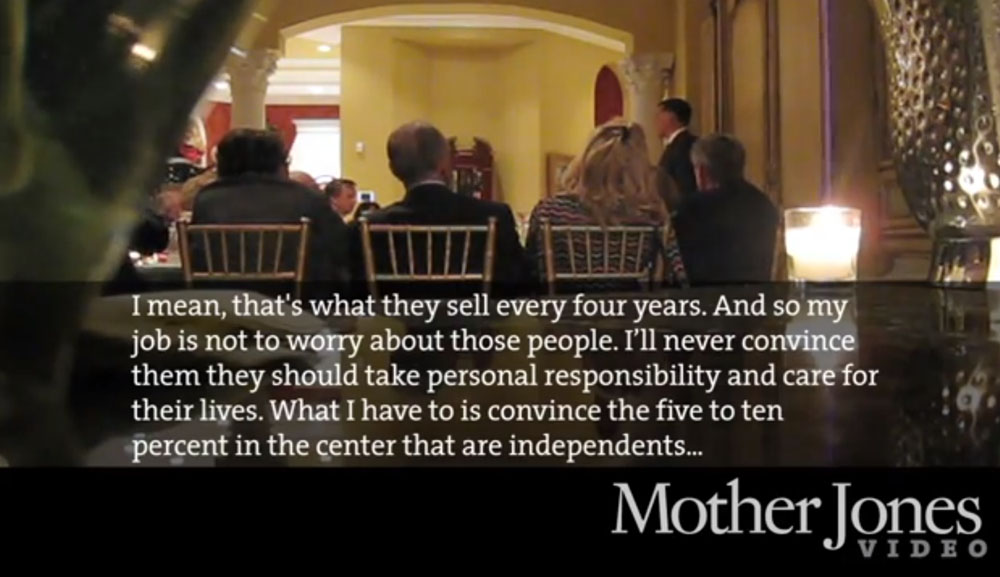

But the second and biggest point of silliness is the notion that we small people have the same power to spy on elites that they have to spy on us. Yes, sometimes it happens. The photo of the cop pepper-spraying a group of already restrained protesters held our national attention for weeks. That was a fine example of sousveillance — someone had a camera ready at the right time. Another brilliant lick of sousveillance was when a waiter (or someone) at a Romney fund-raising event for rich people secretly made a tape of Romney trashing 47 percent of the American people as “takers.” It helped expose Romney as a servant of the rich, and it helped him lose the election.

Edward Snowden’s spying on the spies, then releasing the evidence to the media and to Wikileaks, is the all-time best example of sousveillance. Because of the actions of one very clever nerd, the elites caught red-handed are still squawking and trying to lie their way out it. We got some very useful information on how elites’ surveillance systems operate, though that information will soon enough be obsolete.

But as brilliant as these coups of sousveillance were, such things are always going to be rare and accidental. That is because elites have systems for secrecy that we little people will never have. They are rich, they are ruthless, and they are spending hundreds of billions of dollars (most of it our own tax money) to build walls of secrecy around themselves while monitoring everything we do. The idea that the little cameras in our phones, or built into our glasses, can fix this is seriously dumb. Nevertheless, we need to always keep our cameras handy, and we must be creative in coming up with new ways to spy on elites.

The future of over-the-air television

Hugh Jackman in “Oklahoma,” broadcast yesterday on WUNC-TV

One of my regular themes on this blog is beating down the misconception that digital technologies have made radio obsolete. The opposite is true. Digital technologies have made radio more important than ever. I am, of course, using the broad definition of radio — the wireless transmission of information using the electromagnetic spectrum. Your WIFI router, your cell phone, your car keys — all of them contain radio apparatus, and they all use some part or other of the electromagnetic radio spectrum. By this definition, even television is radio. It’s just that the radio signal used by television is modulated in such a way that it can create an image.

The important thing to know here is that there is only so much radio spectrum, and that there is not enough of it. The only way to manage this limited resource is to regulate the living daylights out of it, and to manage the spectrum wisely and frugally and in the public interest, because radio spectrum is a publicly owned natural resource. That’s what the FCC is for.

Most people get their television these days by connecting to cable or satellite. But about 10 percent of Americans — including me — either can’t or won’t pay the high cost of cable or satellite and get television over the air, through an antenna. This is on my mind right now because I finally was able to find a low-cost antenna ($40), that when placed in my attic and pointed toward Sauratown Mountain can pick up the nearest PBS television station. Up until now, the abbey’s rarely used television (except for watching DVD’s and Blu-ray) has not been able to receive PBS.

I’m not going to get too nerdy on this point, but because I have a strong interest in radio communications and because I have an Extra class amateur radio license, I’m very familiar with radio spectrum and how radio waves propagate differently according to their frequency. Most people, of course, don’t care in the least what frequency their cell phone is using. But we nerds care, and given a particular device we probably can tell you pretty precisely what frequency or “band” it is using. Depending on who your carrier is and whether we’re talking about voice or data, your cell phone is using UHF frequencies between 800 Mhz up to about 2500 Mhz.

The UHF television channels (channel 14 through 69) range from about 470 Mhz to 800 Mhz. This is very valuable radio spectrum, and big players like Verizon want as much of it as they can get. There is no plan at present, as far as I know, to completely toss out broadcast television. But the FCC is working on taking back television spectrum and freeing it up for wireless data.

This is not a bad idea, though I’m always wary when so much money and corporate intrigue are involved. Because radio waves of different frequencies propagate differently, there are some advantages to television vs. cellular frequencies. The lower television frequencies penetrate buildings better and can travel farther. Cellular towers wouldn’t have to be so close together. But because the frequencies are lower, antennas also need to be longer to be efficient. Television frequencies are ideal for devices that are in a fixed location with a larger antenna — for example, in your attic rather than in your pocket. That’s why television ended up on those frequencies in the first place — wisdom and technical savvy exercised years ago by the FCC.

I mentioned that the PBS station nearest to me is on Sauratown Mountain, about 18 miles away. The right technology sitting on that mountain, using television frequencies, would be ideal for finally getting true broadband into a bandwidth-deprived rural home like mine.

Will it happen? First the FCC has to get it right. Then someone has to step in and build the infrastructure. Personally I would like to see a publicly owned, nonprofit system using this spectrum and providing broadband to rural homes and businesses at a reasonable cost. But corporations hate this idea, because the few publicly owned broadband systems in the country are delivering data much faster and cheaper. In North Carolina, corporations even lobbied for, and got, a state law that all but eliminates competition from publicly owned systems. And yes I’m still angry about this, because it shows how easily politicians can be corrupted into serving profit rather than the public interest.

Our job is to keep a close eye on what the FCC is doing and make sure that the public interest is served. Most people don’t realize that the radio spectrum is owned by the public. It is a natural resource, and it is scarce and limited. That’s why it can’t be used without a license, and that’s why it must be closely regulated to prevent misuse and interference. If we don’t keep an eye on the FCC, they’re all the more likely to sell out to profit and betray the public interest. Yes, we “auction” radio spectrum and permit it to be used for profit, but that right always comes with a license and strict terms. There’s always a way of taking the spectrum back if the terms of the license are violated. The radio spectrum ultimately does not belong to Verizon or to any other corporation. It belongs to us.

Now back to PBS for a moment. One of the needs that PBS ought to be serving is keeping the public aware of issues like this. Lord knows the local news won’t. But as far as I can tell, WUNC-TV — North Carolina’s public television system — is letting down on the job. Of course, their budget has been blown apart by the current regime in Raleigh, which I believe prefers that the public be kept in the dark. It appears to me that most of WUNC-TV’s state-produced programming has been heavily featurized and dumbed down. One of this blog’s regular readers is an academic who specializes in this area, so maybe he can comment on the current state of WUNC-TV’s public affairs programming.

An afterword about why regulation is not a violation of individual rights but is absolutely critical: Anyone who holds an amateur radio license is aware of the terms of that license and what kind of violations would cause the FCC to revoke the license. If I tried to use my license to broadcast, as opposed to talking to one other station, I would lose my license. If I repeatedly tried to use the ham bands for political speech or profanity, I would lose my license. If I accepted money for anything I transmitted on the ham bands, I would lose my license. If I got caught even once transmitting on a frequency that I am not authorized to use, I would lose my license. (Try transmitting on a frequency used for law enforcement and see how fast the FCC hunts you down and throws the book at you). If I interfere with another ham radio operator’s lawful rightful to use our frequencies according to the legal terms under which we share those frequencies, I would lose my license. If the use of the radio spectrum was not closely regulated, all your devices that depend on radio, including your GPS device, your cell phone, and the navigation systems of the airplane you’re on, would become unreliable, because there would be no legal means of preventing interference and abuse. I can’t resist getting in the occasional dig at “libertarians.” Mostly, they’re crazy.