Today’s Sunday drive went past RagApple Lassie Vineyards near Rockford in Yadkin County. The vines were looking really good…

Biscuit quest, continued…

Over many months, I have continued to experiment with biscuits. The objective is to make a great biscuit, reasonably true to the Southern standard for good biscuits, but as low-carb as possible, with the lowest possible glycemic index. Flax seed, with which I started experimenting well over a year ago, is only part of the answer, I think. Flax seed, for all its health benefits, tends to make bread gummy if you use too much of it. So how might one counteract the gumminess of flax seed meal?

The best way I’ve found so far is to add soy flour. The caky characteristic of soy flour seems to counteract the gumminess of flax seed meal, giving the biscuit a very satisfactory texture, not only when served hot, but also when served cold.

Here are the proportions I’ve settled on for now, and the proportions I used for the biscuits in the photo above: 1 and 1/3 cup King Arthur whole wheat flour; 1/3 cup flax seed meal; and 1/2 cup soy flour. The biscuits are shortened with coconut oil. I used soy milk, clabbered with a teaspoon of vinegar.

Barley burgers

The barley experiments continue. Barley has a chewiness and heartiness that works nicely in fried patties. The barley burgers above are simple: cooked pearl barley, bound with an egg and whole-wheat bread crumbs and seasoned with chopped onions. I think they’d make a nice breakfast patty if they were seasoned like sausage. That will be the next experiment.

The barley itself was cooked several days ago and stored in the refrigerator. Barley takes a long time to cook, so I like to use a pressure cooker. One part barley to three parts vegetable stock is about right. I leave it in the pressure cooker for about an hour. You want it to soak up as much liquid as possible, with no liquid remaining in the bottom of the pot when the barley is done.

Again, why barley? Because, of all the grains, barley takes the longest to digest and so has a low glycemic index. It sticks to the ribs.

Tragedy and pathos

Reading up on the news this morning, as usual, I read that people by the millions spent much of the afternoon yesterday watching a balloon chase, thinking that a little boy was inside the balloon. Later they learned that there was really no drama at all, and that it might have been a hoax.

I wish that every American had a chance to participate in a sport that English majors take very seriously: Sitting around with other lovers of stories and discussing the question “What is the meaning of this story?”

The boy-in-the-balloon story was never much of a story. It’s even a boring story, and if I had been watching cable TV (I don’t have cable TV) I would have clicked right past it.

Orson Scott Card is one of the few people — or few writers, for that matter — who has a well developed theory of stories. Card believes that stories are a basic human need, that people are constantly hungry for stories. People are so hungry for stories, he believes, that we require stories every day, like food and water. But Card also recognizes that there are good stories and stories that are not so good. If people can’t get good stories, they will consume bad stories.

And so, as stories go, the boy-in-the-balloon story was a junk-food story, high in cable-TV calories but low in nutrition. It contained no meaning. It was pathos. It was merely pathetic.

Meaningless stories about pathos are very different from stories that contain elements of tragedy. Senseless loss of life happens every day. That is always sad, but it is not always tragic. Try as we may, we can’t find much meaning in senseless loss of life. If there is a tragic element (and therefore meaning) in, say, sudden loss of life in a car accident, a large part of the existential element is its very senselessness and meaninglessness. “That’s all? That’s it?” we might ask ourselves.

Some troublemaker in the back of the class pipes up with a question. “What about the senseless death of Princess Diana in a car accident? Did that have any meaning?” He has a smirk on his face as he asks the question, expecting to see his classmates get themselves into knots to try to argue that there was some kind of meaning in Princess Diana’s death.

“No,” says a boy in the front row. “There was no meaning. It was just that she was famous. And pretty.”

But a not-very-pretty girl in glasses, who has read lots of stories about princesses, speaks up. “Princess Diana’s death had pathetic elements, certainly. But it was a tragedy,” she says. “Because her life was a modern fairy tale. She showed millions of people that to be royal had nothing to do with the parents you happened to be born to. To be a princess is about who you are, or what you became. A true princess shines brighter than the dullard prince she married, brighter than the queen. Diana tried to make the world a better place. When she died, it was as though we knew her. She was the people’s princess. When she left us, we were more alone somehow. Her light was so bright that it helped us all to see. Without her, we are on our own now, like children in the woods. We have no princess anymore, unless we can find that princess inside our own selves.”

If you ask Orson Scott Card why a writer would kill off a character that the reader has fallen in love with, this is what he’d say. That in a good story, a beloved character dies so that the reader, missing that character and grieving for that character, will make that character a part of himself or herself. The reader will be changed.

Once upon a time, when I worked on a newspaper copy desk, we actually had serious discussions about where to play a particular story. “People will want to read it,” we might say, “But it’s pure pathos. It has no meaning.” And so we would bury the story.

I don’t think news people have discussions like that very much anymore. On television, and on the web, if it bleeds, it leads.

That’s why I don’t watch the news on television. It isn’t worth the time, because they have too many cameras and pathetic taste in stories.

More on thickening soups

A couple of weeks ago I mentioned barley as a nice way to thicken soups. An even easier way, because it’s something most of us have in our kitchens, is to use a handful of oatmeal.

The soup in the photo is a cream of onion soup, made with soy milk. I threw in some leftover rice and some leftover peas. With soy milk, rich, creamy soups can have zero cholesterol. The combination of oats and rice makes a nice, hearty soup.

A new heirloom

It was not easy to figure out what sort of tables I needed for the main room of my little gothic cottage. Most of the tables one sees in antique stores — at least any table that I stood a chance of affording — were just too spindly and too fancy. I wanted a table with the mass to hold its own in a fairly large room with a 21-foot ceiling, something with a strong Gothic presence. I soon realized that the tables I needed would look more like church furniture than household furniture. Sure enough, in looking online at companies that make furniture for churches, I saw the sort of tables I wanted. They were being sold as altars or offertory tables. They were ungodly expensive, even though most of them seemed to involve veneer and plywood.

Solution: Commission a table from my brother, who also built my kitchen cabinets. No veneer and no plywood, please. The new table is solid cherry. It’s 28 inches wide and four and a half feet long. The legs are three and a half inches square. My brother gave me a steep discount on the cost of the table. But, in a sense, the table is really family property. It went into my brother’s workshop as cherry boards and came out as an heirloom for his grandchildren.

I’m going to commission two more tables. One will have the same dimensions as the first table; the other will be shorter. Two of the tables will sit at the sides of the room normally. But for special occasions the tables will be lined up in the center of the room for a 12-foot feasting table.

Now where the dickens am I going to find suitable chairs?

Another piece arrived unexpected this weekend: a rug. My sister found it at a moving sale. She knows my color scheme here, so she bought it for me. It’s a wool rug from a famous rug maker, and it was a steal. The cat approves.

Over the river and through the woods

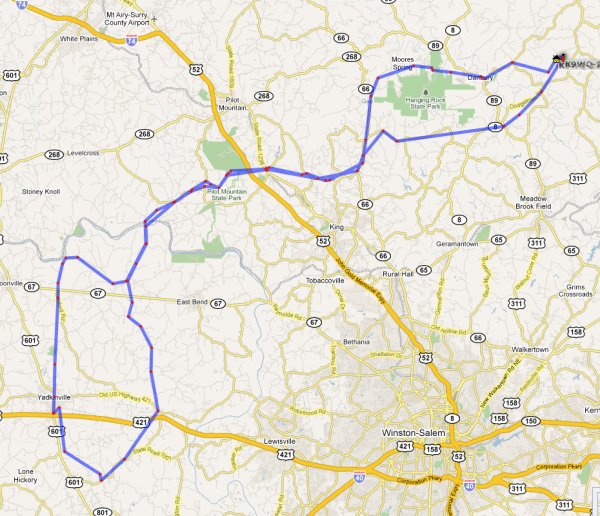

Round trip — more than 100 miles

I drove to Yadkin County today to visit family. It was good weather for photography, and the leaves were just beginning to turn, so I figured it was a good day to document the route from northern Stokes County, where I live, to the Yadkin Valley, where most of my family live, and where I grew up.

When I made the decision to move to Stokes County from California, it was after much deliberation. I weighed many factors. It’s hard to get to northern Stokes County. The roads are narrow, and crooked. Most people would need a map. It’s not a place where a commuter would want to live. But to me, these were positives, not negatives. I wanted to find a sweet spot between remoteness and access to commercial and medical centers. If I want to shop at Whole Foods, I can get to one (in Winston-Salem) in about an hour. If I needed to get to a major medical center, that’s also about an hour by road, but a few minutes by helicopter. And they do have helicopters.

If I want to visit family in Yadkin County, I have to drive for more than an hour. But what a drive it is. The route crosses two rivers (the Dan and the Yadkin), and runs through the shadows of the Sauratown Mountain range. Stokes County is so isolated that it has its own little isolated mountain range! It’s some of the best scenery to be found in the Yadkin Valley and the Blue Ridge foothills.

So here’s a photographic essay on the trip from my house to my mother’s house in Yadkin County. For the sake of photographic honesty, please be aware that I have focused on the picturesque and the historic. There’s plenty of plainness and a certain amount of rural squalor along the way. But why takes pictures of that?

Leaving home. Now that the house is done, I need to get started on the landscaping, don’t I?

The unpaved road above my house, past a neighbor’s horse pasture

Priddy’s General Store, which appeared in the cult film Cabin Fever

This building in Danbury was once a church. Now AA meets there, according to the sign out front.

The old Stokes County courthouse

I believe this used to be the Danbury town hall. Now it’s a lawyer’s office.

The entrance to Hanging Rock State Park, a few miles from Danbury. Just as in California, state parks are often under-appreciated, and awesome.

Hanging Rock, from Moore’s Spring Road

Hanging Rock, also from Moore’s Spring Road

Approaching Pilot Mountain. Do you know the word “monadnock”? Culturally, the thing to know about Pilot Mountain is that it was called “Mount Pilot” in the Andy Griffith Show. This is Mayberry Country, remember.

Old mill at Pinnacle. Pinnacle was the setting for the indie movie Junebug.

Pilot Mountain, looking over the roof of the Pinnacle post office

A pumpkin patch on the south side of Pilot Mountain

Coming into Siloam

An old storefront in Siloam. If agricultural tourism and the popularity of the Yadkin Valley Wine Region ever reach critical mass, what a great little restaurant this would make.

Across the road from the Siloam storefront. I have no idea what this little building is, but it must have some historical importance, because someone keeps it up.

Siloam will probably forever remain known for the night of Feb. 23, 1975, when an old suspension bridge across the Yadkin River collapsed, killing four people and injuring 16. This is the new bridge.

The big house at Siloam. Grand farms were not the rule in this area. Small family farms were much more common. But Siloam clearly was once a hot spot. Not only was there fertile land in the river bottom, but there was also a railway line. It clearly was enough to make a few farmers rich.

Pilot Mountain again, when I passed it on my way home

The history of this area — at least the agricultural history — is best read in the remaining outbuildings. Certainly more than a few big barns like this one remain. More modest barns on the old family farms are common, and hundreds if not thousands of old tobacco barns remain. Still, an untold number of fine old outbuildings have fallen down and rotted away.

Persimmons

The diameter of this persimmon is a little bigger than a quarter.

Persimmon trees can hide at the edge of the woods during the spring and summer. But in the fall when they’re loaded with fruit, they might as well be flashing with Christmas tree lights. I discovered this persimmon tree on the edge of my woods. I had not noticed it until a couple of weeks ago.

I’m not certain, but I believe that the big, hard, acorn-shaped persimmons that are grown commercially in California are Asian persimmons. Whereas the persimmons that grow wild here in the North Carolina Piedmont and the Blue Ridge foothills are the American persimmon.

What are they good for, you ask. Pudding! I hope to gather enough persimmons to make a pudding before the season is over. If I succeed, I’ll post some photos.

The native persimmons are not fit to eat until they fall from the tree, ripe. Before they are ripe they are unbearably astringent. October frosts can quicken the ripening. But after they fall to the ground, you’ve got to get to them before the wildlife do. There are so many hungry mouths around here.

Cosmos

Gourmet magazine, R.I.P.

My mother’s mother’s biscuit pan, now a working heirloom

It is strange that, at a time when Americans’ interest in food and culture seems to be reawakening, Gourmet magazine goes out of business. Much has been written about the end of Gourmet, but I very much agree with what many of its readers and former readers have said: Gourmet was much more than a snooty magazine. It always implicitly understood the intimate connection between food and culture.

These days, when even young top-of-the-world Internet whiz kids like Jonah Lehrer can not only write lyrically about home cooking, but also write for Gourmet magazine, it almost feels as though an era has ended when it had barely begun.

Like Jonah Lehrer, I strongly suspect that an interest in cooking often if not always has its roots in childhood. These childhood memories were not only about learning about food and cooking, they also taught us about whatever culture we were born into.

I was a child in the 1950s, living in North Carolina’s Yadkin Valley. My relatives lived mostly in the North Carolina Piedmont and foothills and up into the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. In those days, relatives visited relatives, and often Sunday dinner (which was served right after church) was involved. If one stayed overnight, as sometimes happened, you got not only to sleep in an unheated bedroom under a deep pile of homemade quilts. You also got breakfast.

Whether it was breakfast or dinner, there were always biscuits. As a child, I began to realize that everybody’s made-from-scratch biscuits were very, very different. To this day, if you put a hot time-warp biscuit in front of me on a cool October morning, I believe I would be able to identify the aunt, grandmother, or older cousin who made it.

Let’s hope that the spirit of Gourmet magazine lives on in our blogs, as we learn from each other’s cooking and culture.