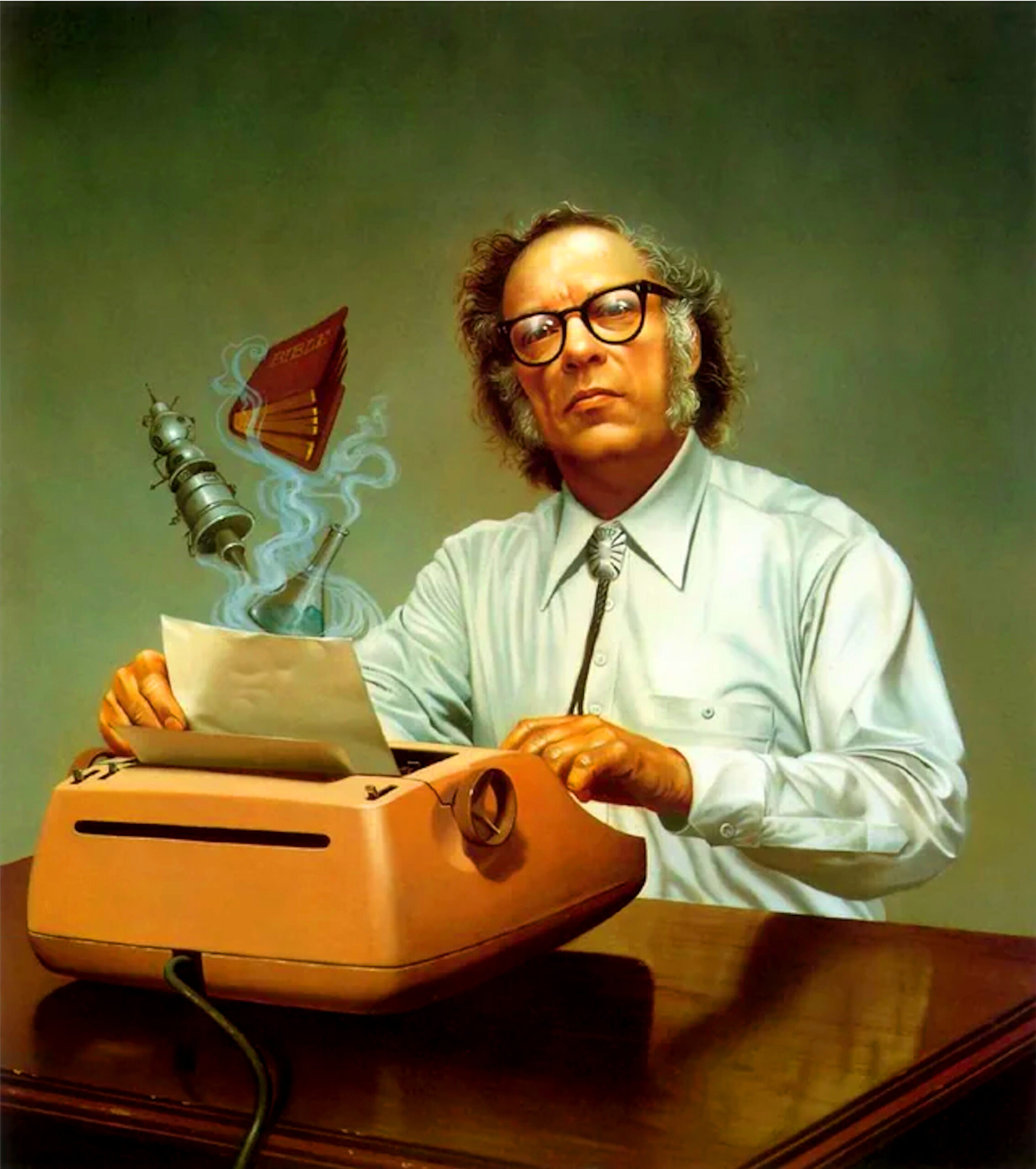

My IBM Selectric I, made in 1974, restored by a former IBM field engineer. The Selectric I typewriters were introduced in 1961. Click here for high resolution version.

I have written in the past about how today’s taste in automobile design is for aggressive-looking, mean-looking, vehicles. Even Volkswagen, whose designs used to charm people, now makes cars that look like they’re sneering at you. The 300-horsepower Arteon Volkswagen looks like a bully, with a vaguely sadistic expression. The sociology of this is no doubt disturbing. But let’s talk about designs that charm, and soothe, and purr, and lower one’s blood pressure, like petting the cat.

The IBM Selectric I typewriter, I believe, is not only the most beautiful typewriter ever made, but also is one of the most beautiful machines ever made. It was designed by Eliot Noyes. It first came on the market in 1961. The Selectric II came along in 1973, and the Selectric III in 1980. The Selectric II and III, though still beautiful machines, don’t have the please-pet-me cat-like curves of the Selectric I, and they’re too wide and industrial-looking to be charming.

Maybe not everyone would see a cat in the design of the Selectric I, but I do, not least because it reminds me of the Jaguar S-type, which was introduced during the same era as the Selectric I, in 1963. I have not been able to find the name of any particular designer for the Jaguar cars. But it seems clear that Jaguar design reflects the taste of Sir William Lyons, also known as “Mr. Jaguar,” who ran the company until he retired in 1972.

For five years, I have been driving a Fiat 500. It’s mouse gray. Though the Fiat 500 is one of the most popular cars in the world, Americans (other than a few people like me) wouldn’t buy them, and Fiat stopped selling them in the U.S. My guess is that the unpopularity of the Fiat 500 is not just because it’s small. It also looks like a mouse, or maybe a vole. Driving a Fiat 500, I suspect, is very healthy for one’s blood pressure, at least until some mean-looking car with a mean driver gets behind you.

It pleases me greatly that typewriters are having a renaissance. And it’s not just typewriter veterans like me. Most of the interest is coming from members of Generation Z. There is a very active Reddit group. It’s charming, really, that young people buy typewriters before they have the slightest idea how to use them. For example, with manual typewriters, they don’t understand that one strikes the keys rather than pressing them. A common question with older typewriters is: Where is the “1” key? That drove me crazy, too, when I was about nine years old, until someone told me to try the lower-case “L” key. Nor do the Generation Z types know that, to make an exclamation point, one first types a period, then backspaces and types an apostrophe. The Selectrics, though, all along had enough room on those tilt-and-rotate type balls for a “1” and a “!”.

Restoration of the IBM Selectrics is very challenging. Fortunately there are still a few old guys around who used to work for IBM. Some younger people are learning. Parts, of course, are no longer made. Some nylon parts in the Selectrics, such as the main drive hub, almost always have cracked, and that doomed an old Selectric. This problem has been solved by people who use 3D printers to make replacement parts, usually out of aluminum.

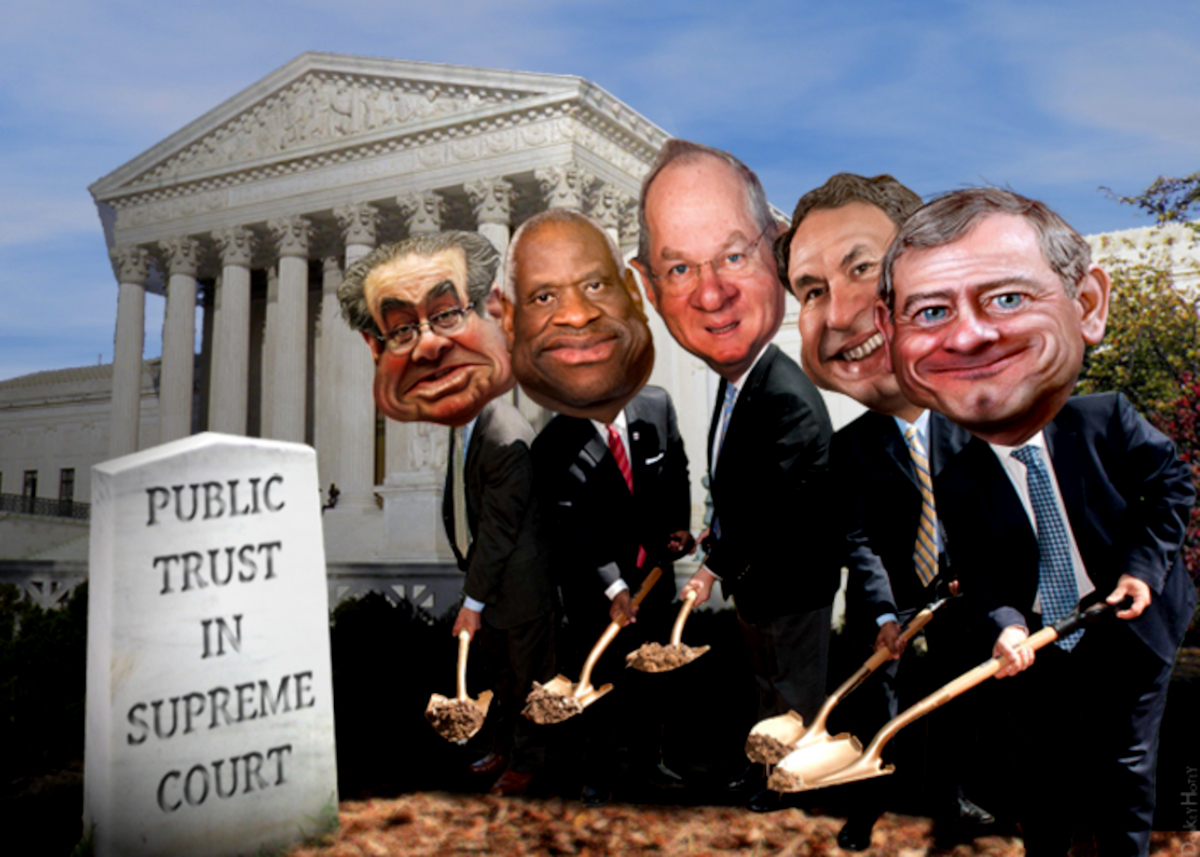

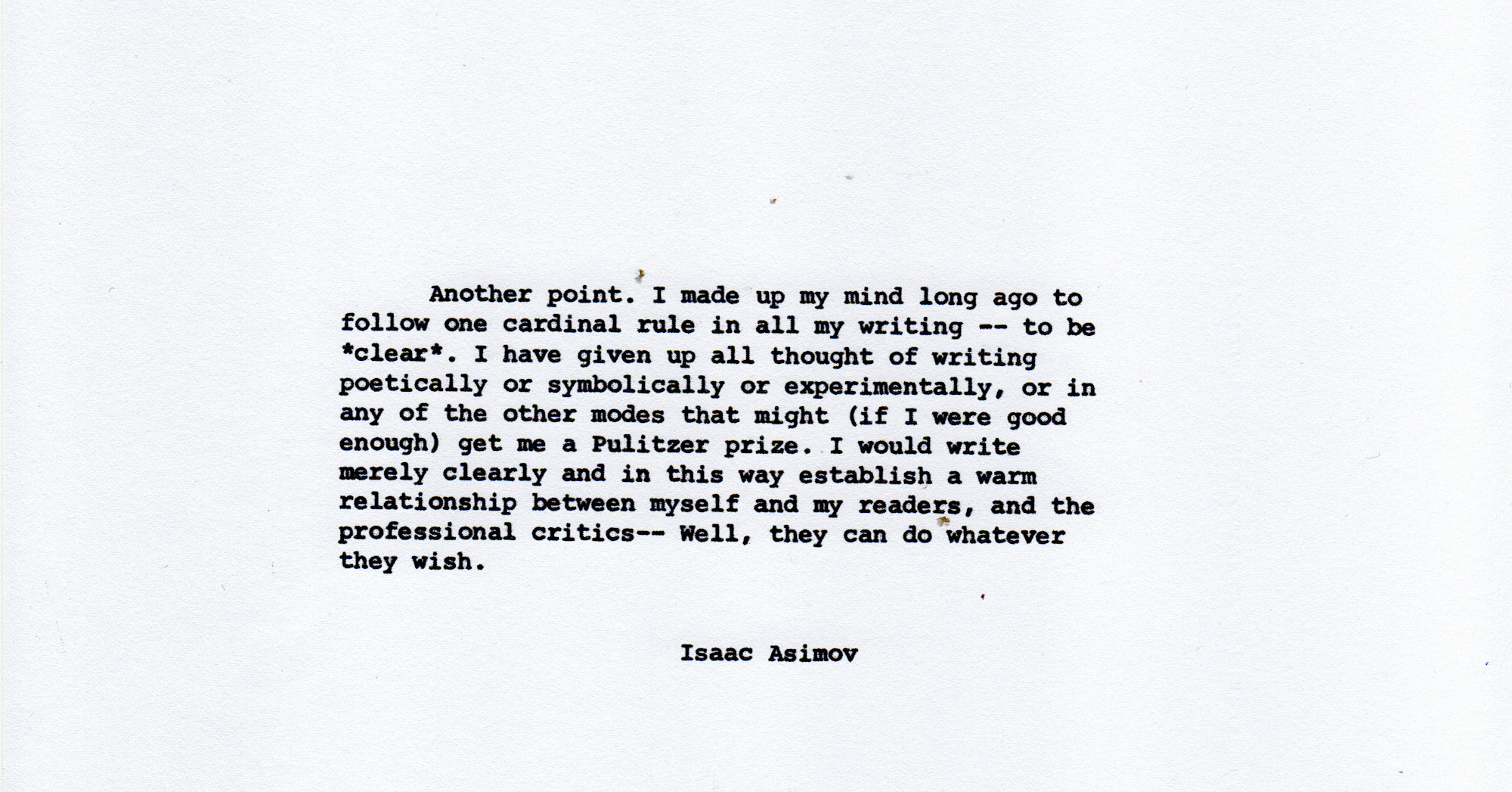

There also is a lot of interest in learning what kind of typewriters our favorite writers used to use. J.R.R. Tolkien favored the very expensive Varityper machines. Isaac Asimov loved his Selectric I. There are photographs of Hunter S. Thompson with his Selectric I, which was red, like mine. According to the Washington Post, Jack Kerouac used an Underwood portable, Ernest Hemingway used a Royal Quiet Deluxe, and Ayn Rand used a Remington portable. It is sometimes said that it was from Remington Rand that Ayn Rand chose her last name (her birth name was Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum), but I believe that has been disproven. I have rarely typed on Remington typewriters, which is fine with me since I can’t stand Ayn Rand.

Still today, IBM is proud of the Selectric typewriter’s history, and there are articles on IBM’s web site including an article on the Selectrics’ cultural impact.

My bossy 15-year-old cat, Lily, would never tolerate another cat in the house, preventing me from becoming a crazy old cat person. But homeless and scroungy old typewriters, like cats, beg to be rescued, fixed up, and looked after in a forever home.

⬆︎ A 1966 Jaguar S-type saloon. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

⬆︎ A Fiat 500. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

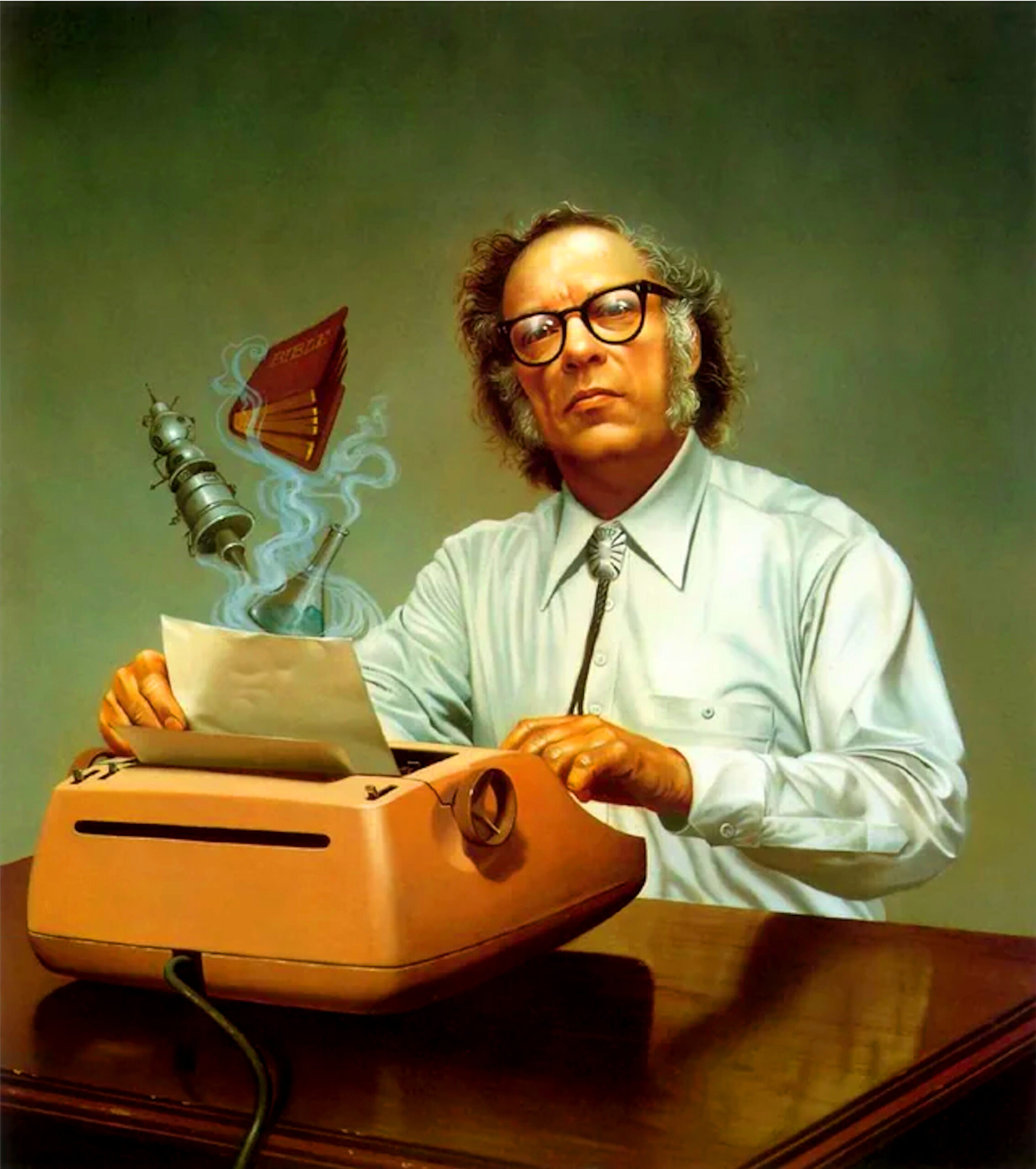

⬆︎ Isaac Asimov with his IBM Selectric I. The illustration, by Rowena Morrill, was for the cover of Asimov’s Opus 200.

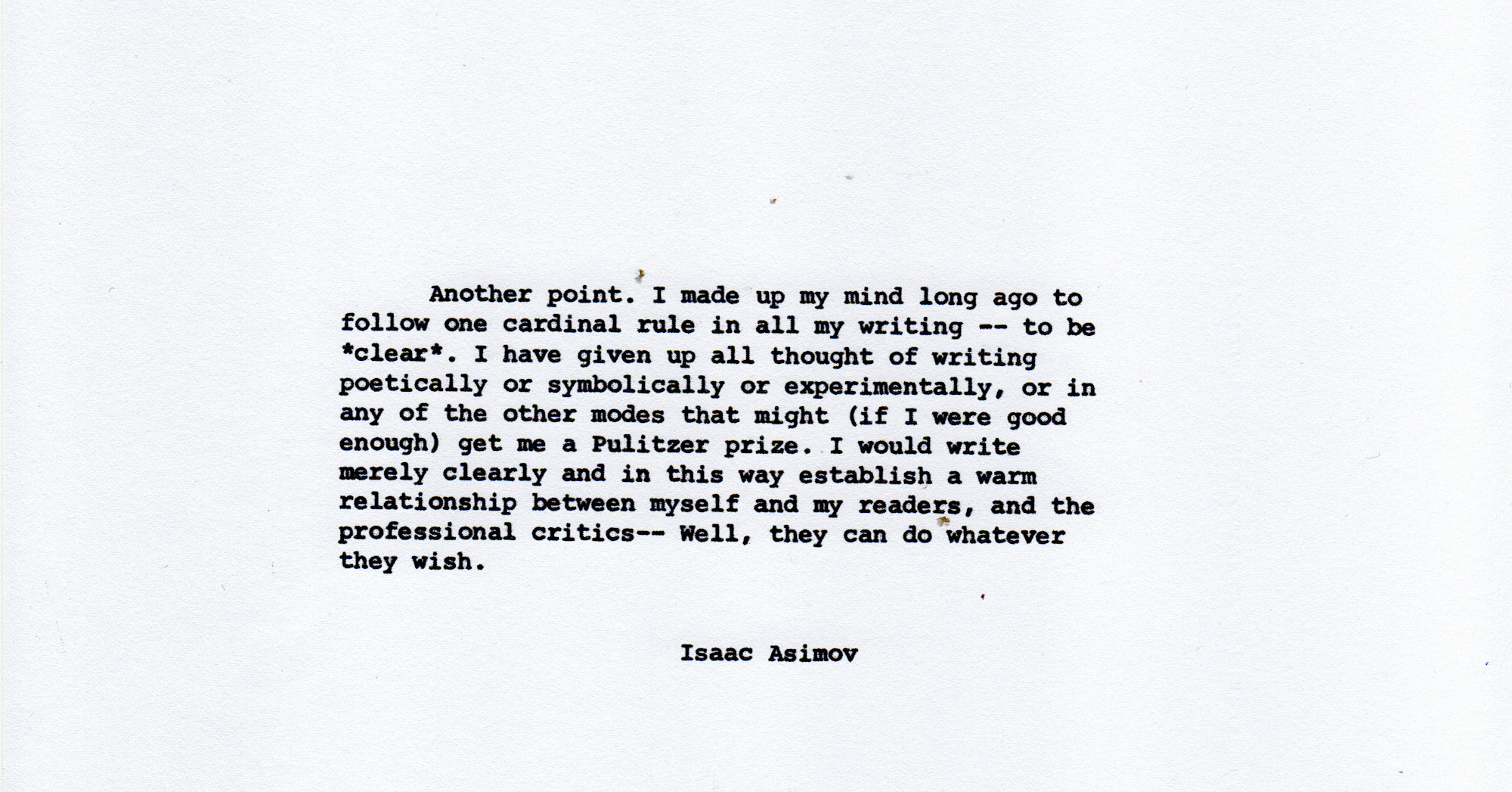

⬆︎ Type sample from my IBM Selectric I, which uses a fabric (as opposed to film) ribbon.