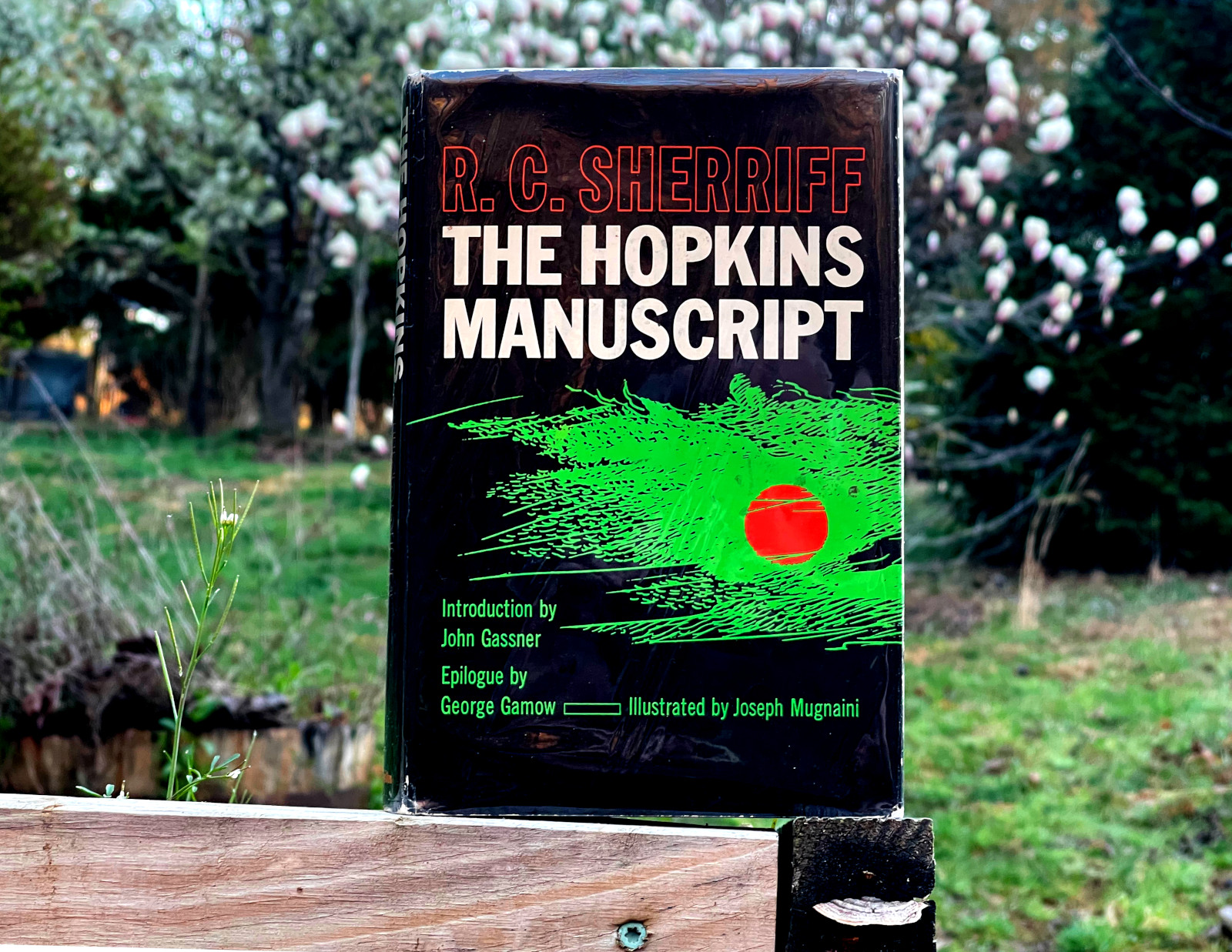

The Hopkins Manuscript. R.C. Sherriff, Macmillan, 1939.

This book got to me. I finished it just before sunset, and all evening, as a nearly full moon rose, I was spooked by a sense of unreality as I worked my way out of the world of the novel and back to the real world. I considered pouring myself some Scotch (but didn’t). How did R.C. Sherriff tell his story so compellingly that, in spite of the improbable science of his falling moon, we suspend all disbelief and enter that state of total immersion that, as readers, we long for?

First of all, the novel is beautifully written. As for why it’s so compelling, I think it’s because he tells the story through the eyes of very ordinary people living in very ordinary circumstances — a village and small farm in Worcestershire. The main character is Edgar Hopkins, a former schoolmaster and rather dull man who, upon inheriting some money, settles down on his little hilltop farm and breeds poultry as a hobby. There are side trips by train to London, but it’s on this farm and in the nearby village where most of the story takes place.

The novel was first published in 1939. My copy of the book, which I bought from a used book seller, is a book club edition from 1963. A third edition (or possibly the fourth or fifth including a paperback in the 1950s) was published this year and was reviewed in the Washington Post: The moon falls to Earth in a 1939 novel that remains chillingly relevant.

Robert Cedrick Sherriff was better known as a playwright and screenwriter than as a novelist. He wrote Journey’s End, a play about World War I that opened at London’s Savoy Theater in 1929 and ran for 594 performances. Sherriff was a veteran of that war, and it seems certain that his experiences during the war had much to do with the emotional tone of The Hopkins Manuscript, a strange blend of optimism and pessimism that Sherriff skillfully pulls off. Sherriff was born in 1896 and died in 1975. After the war, in which he was badly wounded, Sherriff led an ordinary life as an insurance adjuster. He returned to Oxford in 1931 to study history. He probably was gay and was probably an ephebophile. Journey’s End was originally written as an all-male play, a fund-raiser to buy a new boat for the Kingston Rowing Club, which he coached. There are two characters in The Hopkins Manuscript that, I think, were inspired by his ephebophilia.

Much of the beauty of this book is in the clear, elegant, and yet modest writing. I’m reminded of Isaac Asimov’s author’s note for Nemesis:

“Another point: I made up my mind long ago to follow one cardinal rule in all my writing — to be clear. I have given up all thought of writing poetically or symbolically or experimentally, or in any of the other modes that might (if I were good enough) get me a Pulitzer prize. I would write merely clearly and in this way establish a warm relationship between myself and my readers, and the professional critics– Well, they can do whatever they wish.”

Asimov steers clear of snark, but it’s clear enough what he thinks of writers who bamboozle the critics (and even some readers) with quirky and affected writing styles. And Asimov is being a touch ironic with his choice of the word merely, because Asimov certainly knew that to write clearly is hard. Only the best writers can do it. I wish I’d known about R.C. Sherriff a long time ago.

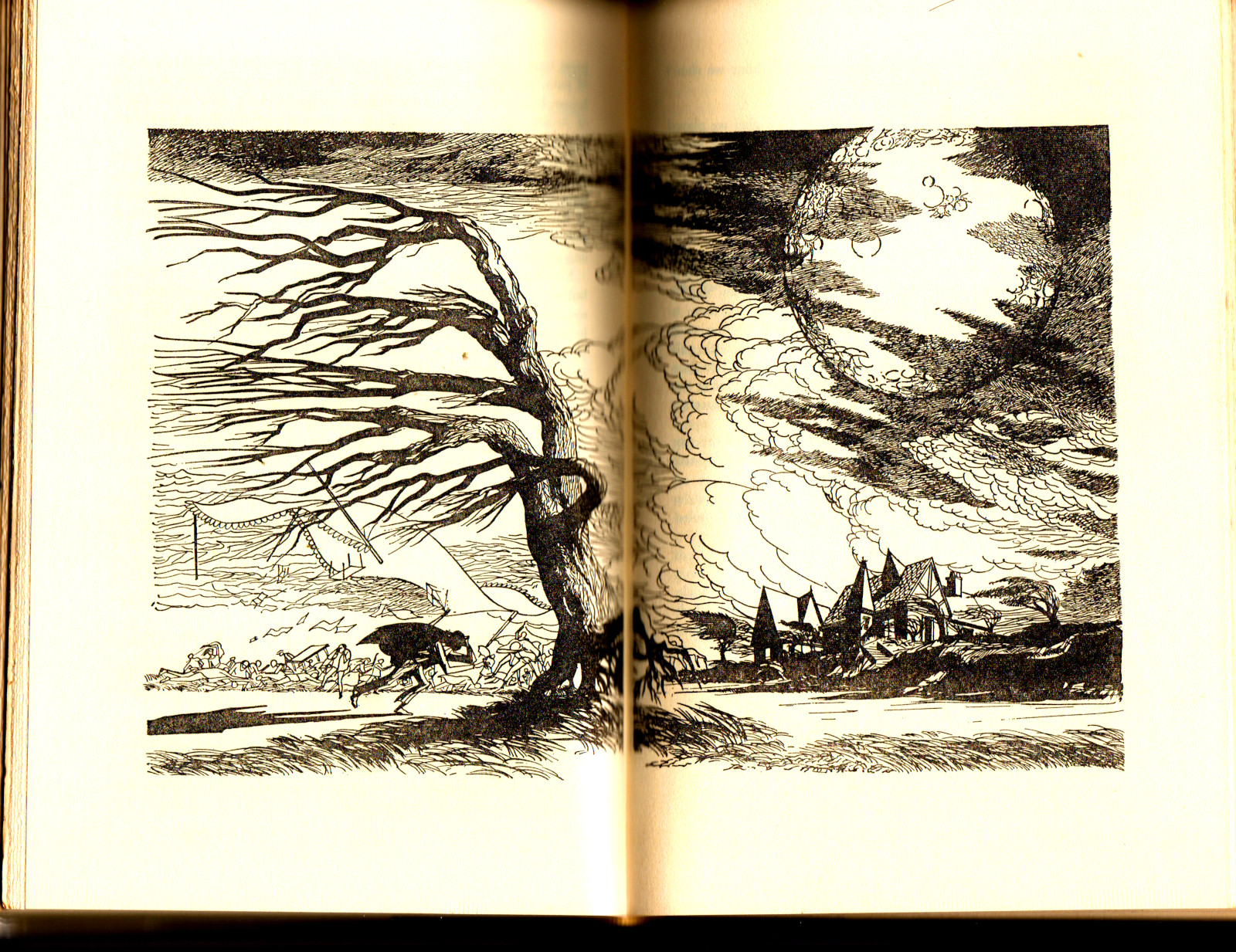

My edition of the book includes illustrations by Joseph Mugnaini.