Today, Sweden and Finland formally applied for membership in NATO. (Washington Post story here.) This is a very big deal. Remember when the Neocon war hawks of the Bush-Cheney administration tried to teach us that diplomacy no longer matters and strove to establish an American empire armed to the teeth, fueled by oil, and aligned with authoritarian oil countries? And then, eight years after the Bush-Cheney administration, Putin’s friend Donald Trump wanted to destroy NATO with a U.S. withdrawal, and, like Bush-Cheney, sucked up to the oil countries (that includes Russia) rather than looking north. That kind of foolishness might have been weakly arguable then. But now, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the exposure of Russia’s weakness and Putin’s misjudgments, and a rapid realignment of the Western democracies, the Republican madness — oil and authoritarianism — is obvious.

It may seem surprising that this realignment happened so quickly — in a matter of weeks, really. Partly, of course, that was the product of diplomacy. (One of the miracles of the Biden administration is how quickly Biden re-professionalized the State Department after Trump turned it over to hacks with conflicts of interest.) But in fact the situation was changing before Russia invaded Ukraine. This short report from the RAND Corporation, dated September 15, 2021, is about how three key Nordic countries — Norway, Sweden, and Finland — had in recent years become increasingly concerned about deteriorating relations with Russia:

“Overall, Norway, Sweden, and Finland have dramatically shifted their plans and actions in response to Russian threats in the European Arctic. For the United States, this change could represent an opportunity to further strengthen cooperation with its key allies and partners, helping to enhance security in the region and better counter Russian challenges in the northernmost reaches of Europe.”

If Republicans had remained in control, the consequences for the West would have been disastrous as the strategic and economic opportunities were lost and as the U.S. acted in favor of the Russia kleptocracy rather than our allies, the European democracies.

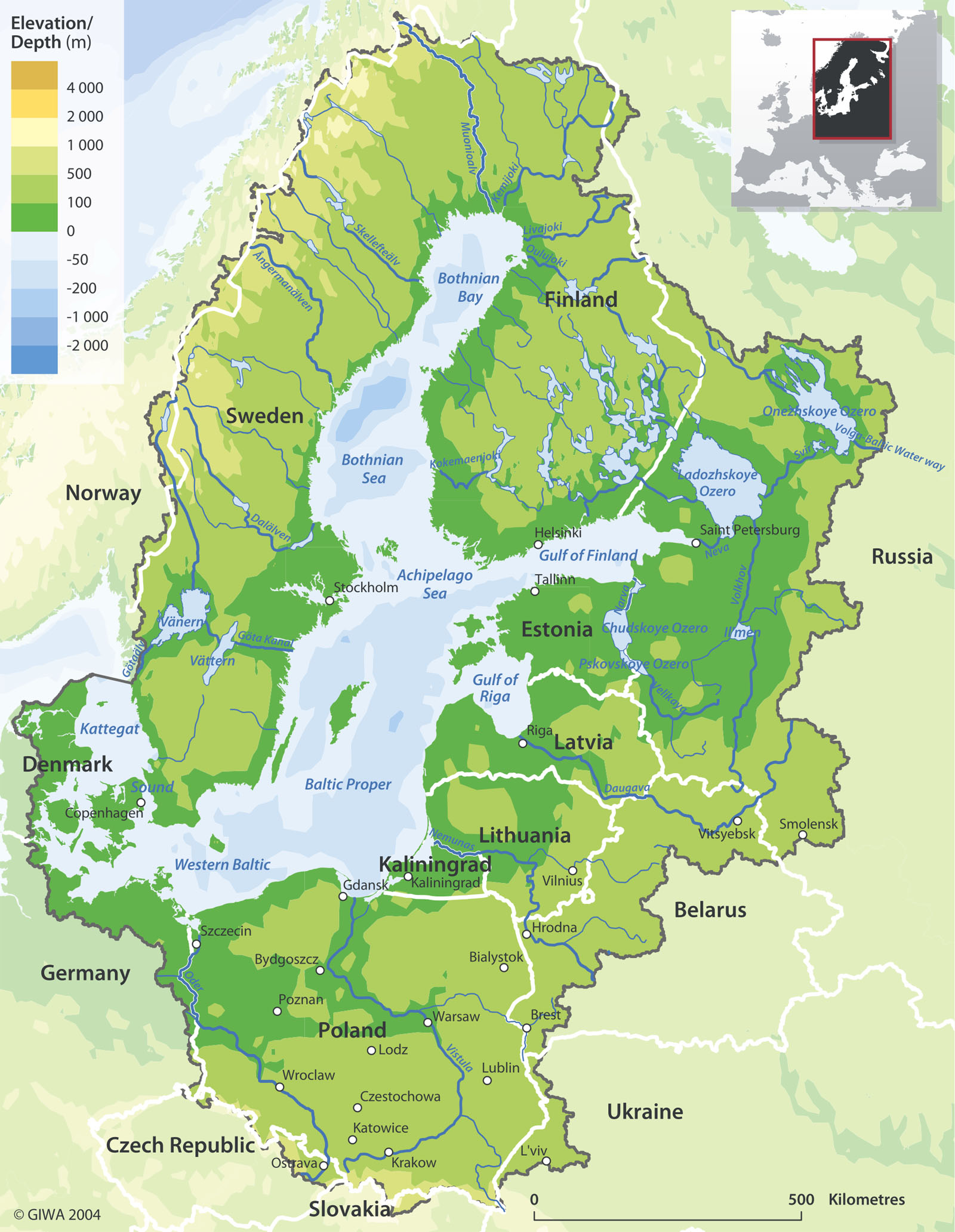

Norway has been a member of NATO since its beginning, in 1949. The admission of Sweden and Finland probably would be almost automatic, but Turkey has thrown some sand into the gears. Turkey’s reservations (mentioned in the Washington Post story above) seem rather silly, but it’s easy to suspect that Turkey’s underlying gripe (other than blowing a kiss at Putin) is that, as the Arctic becomes more and more important in a warming climate and as the world turns away from oil, Mediterranean countries such as Turkey become less and less important. One of the great advances from making oil obsolete will be making the oil countries obsolete. The Baltic Sea will become the new Mediterranean.

It was a book about the economic future of Scotland that first got me thinking about how important the Arctic will become as the climate warms, as ice melts, and as a navigable sea route to Asia opens up through the Baltic Sea. Russia and the Baltic countries are already preparing for the economic changes this will bring. Sweden and Finland joining NATO, I would think, will have economic consequences for the West far beyond its consequences for mutual security and defense.

The old kleptocratic order based on oil created billionaires literally by the thousands. Many of those billionaires are oligarchs like Putin who also have countries to rule and interests to protect. They won’t go down easily, no matter how many yachts we confiscate. This is what is behind much of the geopolitical drama through which we are living at present. Trump, a puppet of that old order, did everything he could to swing the United States away from a new order and toward the old. But four years under Trump wasn’t enough to convert the institutions of democracy into the tools of an autocrat (drain the swamp!) and turn the United States into Russia. If Republicans gain full control of the government again, it’s hard to imagine any result other than geopolitical disaster. If there is a next time, they’ll move faster and more ruthlessly.

I don’t mean to sound pessimistic. As long as the Republican Party — the clueless tool of the .1 percent — can be kept out of power, and as long as the .1 percent who own their own countries don’t start using their nukes (big if’s unfortunately), then the immense military and economic power of the U.S. can help lead the progress toward a new order — more democratic, more sustainable, more fair, and with a prosperity more equally shared. The alternative is a United States fleeced of its wealth by kleptocrats and beaten down by a white Christian police state.