The Enchanted Forest, John Anster Christian Fitzgerald, 1819-1906

Where have all the fairies gone?

We could ask this question two different ways, depending on how you see the world. If you believe that fairies exist (or used to exist), then the question is literal. If you don’t believe in fairies, then there is still a serious question here, a cultural question. Why were fairies once such an important part of human lore? When did we lose interest in fairies? Why?

A friend who lives in France and who knows about (and shares) my interest in the Celts recently sent me a book, The Celtic Twilight, by the Irish poet W.B. Yeats. The book was first published in 1893. Yeats was a mystic, and I’m pretty sure he believed in fairies — or at least very much wanted to. In this book, he travels in rural Ireland and asks people to tell him what they know about fairies. Faeries were already fading then. But they were still very much a part of rural life and the Irish belief system.

I am certainly not the only person to wonder where the fairies have gone. I Googled for the words “where have all the fairies gone” and got a number of little articles. Most are like this. Those articles use words such as “spirit,” “vibration,” “devic,” and “plane.” Though it is harmless, this type of credulous, too-magical thinking makes me cringe. But I also found this, a much smarter and more thoughtful piece. The author thinks that we reached peak fairy around 1926. He thinks that it was the automobile that ruined the world for fairies. This is not just because cars are noisy and are made of metal (fairies hate iron), but because we stopped walking. In particular, we stopped walking in quiet places where nature is still unspoiled.

Though it’s bad manners to quote authors’ last paragraphs, I’ll make an exception here, because I think it’s important: “So, I’m pretty sure cars killed off the fairies and reduced the trove of local stories. And I’m also pretty sure of this: these could be revived if only we got out and about by foot more often, especially where the pavement ends.”

Rational as the author is, clearly he wants the fairies back. I do, too.

Often I stand in my upstairs windows, which face into the woods, downhill toward a little stream. Many times from those windows I have seen the white deer. I have seen an owl perched in the huge old beech tree that overhangs the big rock. The owl flew away on enormous wings when it saw me watching. The white deer, I believe, sleeps under the big rock sometimes. I have seen the trees crowded with hundreds of crows. The crows increasingly seem to like those woods — a positive sign, I think, of something. Noisy as the crows are (they come almost every day), I love the sound they make. The crows also nest in the woods. During the spring I watch them gliding in and out to their nests through holes in the heavy green canopy. One year, a mama fox raised two cubs in those woods. Out of the woods come squirrels, who sometimes get onto the roof of the house, and possums, for whom I leave snacks on the deck. In the spring, the bottom of the little valley is densely strewn with May apples. After a heavy rain, the stream almost roars as the water cascades over the rocks. The water, which at times has been cloudy, is remarkably clear and clean at present. These upstairs windows face west. The full moon sets in the woods, early in the morning. The wind in the trees sounds very different in the winter than in the summer. But particularly in the summer, the wind in the leaves sounds remarkably like the sea. The woods go on and on for miles. You’d have to cross some roads, but I’m pretty sure that one could walk all the way to Quebec from here, up the spine of the Appalachian Mountains, without really leaving the woods.

And so, reading W.B. Yeats’ carefully curated fairy stories from the 19th Century, I ask myself: Shouldn’t there be fairies in those woods? Should I hide the cars up the hill? Would I have to squint and look for them out of the edges of my eyes? Should I try taking naps on the big rock, under the beech tree? Would I have to eat some mushrooms? What sort of fairies might they be? Would they like me? Should I post a little sign, “Fairies welcome here”?

But seriously, the cultural loss is devastating. The 19th Century Irish country people whom Yeats interviewed about fairies were nominally Catholic, but I get the strong impression that Catholicism was a very weak force compared with the ancient folk beliefs. Priests were to be made fun of, but you’d better listen to what the fairies say. Whereas, if I hiked to the north and interviewed some neighbors, they’d know plenty of church talk, but they’d be utterly empty of imagination. And how many of them still walk in the woods?

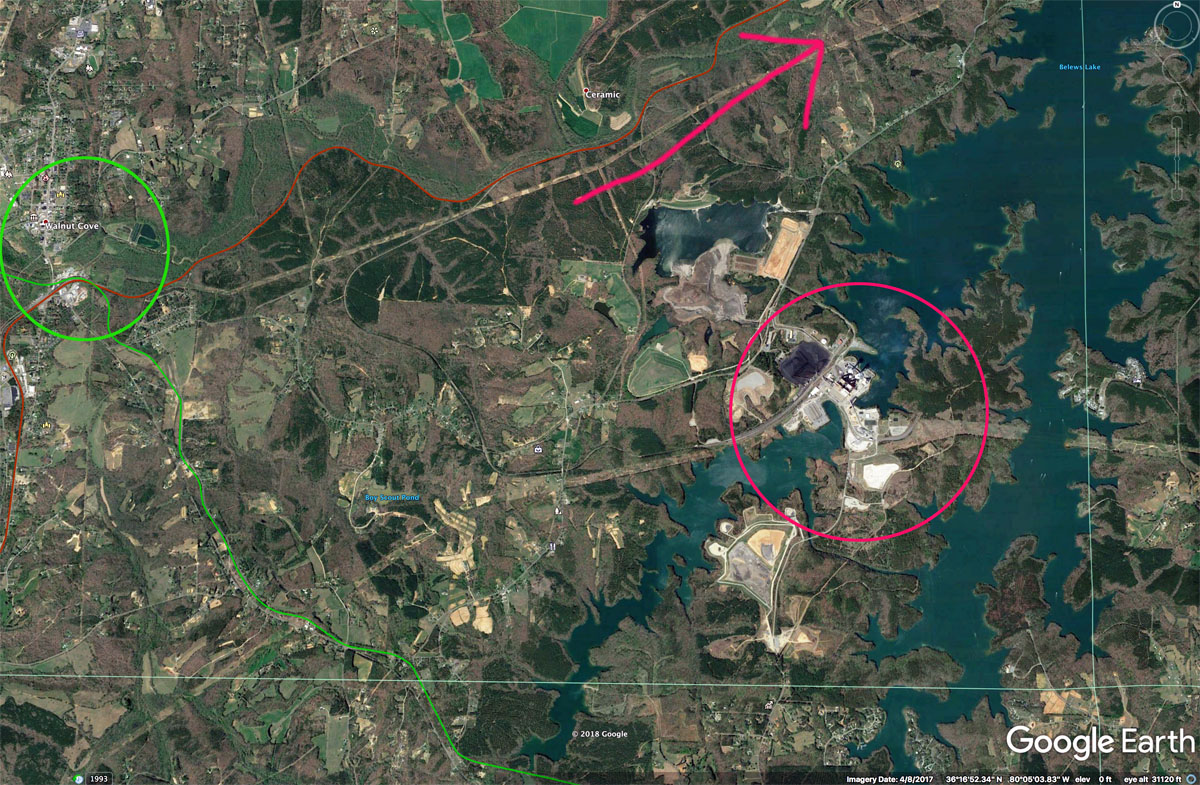

There was a brilliant piece in last Sunday’s New York Times by E.O. Wilson, the biologist. He is arguing for the Half-Earth project, which he believes is necessary if the human species is to survive. The Half-Earth project calls for setting aside half of the earth as habitat for other species. Humans would keep to their own half, and in a sustainable way. That’s a brilliant idea. Maybe, then, there’d be room enough on earth for the fairies, too. Meanwhile I’ve got a little spot for them to help tide them over, if they’d like to have it.

If E.O. Wilson is right, and if we don’t make room for earth’s other creatures, then we’ll be next. It was just that the fairies went first.

Click here for high-resolution version