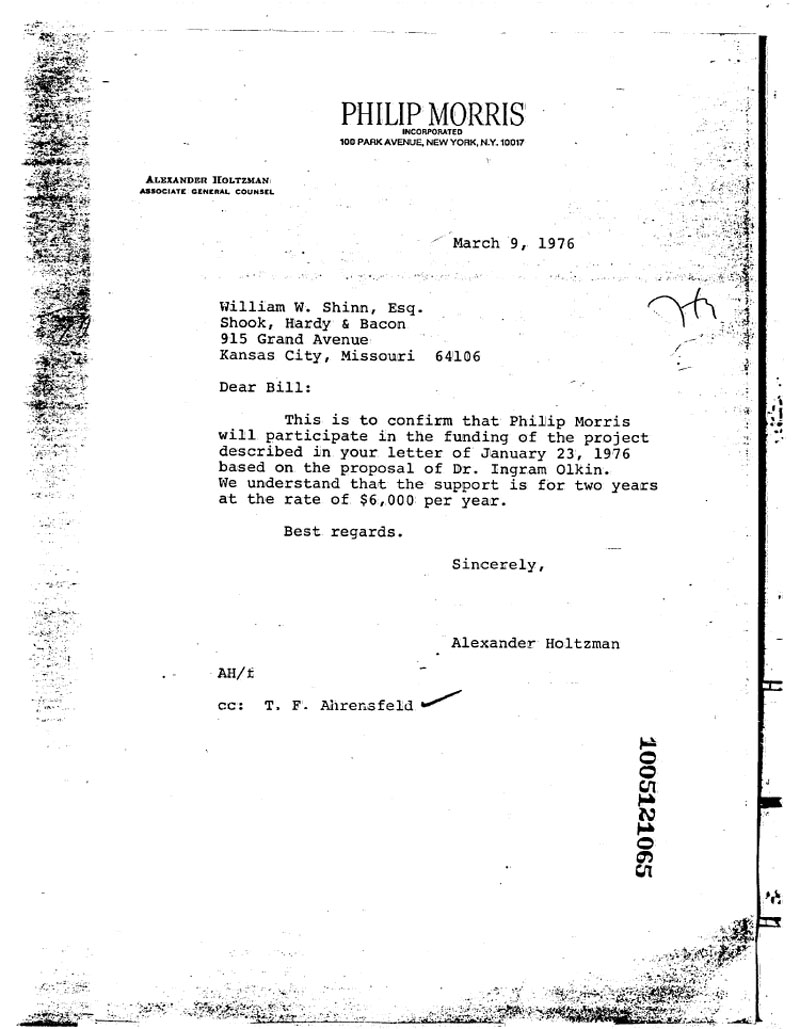

One of the authors of the study, Ingram Olkin, has been doing propaganda work for corporations since the 1970s.

When the story first came out on Sept. 3 about the Stanford study that slammed organic foods, was I the only person who caught a strong whiff of propaganda?

At the time, there wasn’t much that a non-expert could say in response. One just has to wait for experts to have time to respond. The unfortunate thing is, the responses never get the buzz that the original propaganda splash gets.

The article, by the way, was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine. You can’t even read it without a pricey subscription. But clearly someone at Stanford made a big publicity push before the article was published, to get highly spun articles into the press, articles like the one in the New York Times.

The most damning piece of information to come out so far is that one of the authors of the study, Ingram Olkin, has been doing corporate dirty work since the 1970s. He was behind much of the data cited by tobacco companies that denied the link between cigarettes and cancer.

Some in the blogosphere are connecting dots that would link the release of the Stanford study to the campaign against California’s proposition 37, which would require the labeling of genetically modified foods.

There also have been responses from academics at other universities. But these things are slow. It’s going to take more time for all the dirt on the Stanford study to come out. As for the science and statistics involved, I’m not qualified to judge. But keep in mind that the Stanford study did not involve any new research. It was a “meta-study,” a statistical crunching of numbers gathered in previous studies. And it was just such statistical mangling that Ingram Olkin brought to the science on cigarettes and cancer.

One thing is for sure: the ugliness of the outpouring of smugness, self-righteousness and triumphalism from the propagandists for industrial agriculture. The smugness and contempt just ooze from a couple of these essays in the New York Times by Lomborg and Wilcox. I thought it was us organic types who were supposed to be smug.

Political propaganda generally can be shot down rapidly. An exception was the propaganda around weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. It took months for the lies of the Bush administration to be exposed. Scientific propaganda is always slow to be shot down. Science works slowly. That’s why the disinformation campaign about cigarettes and cancer went on for so many years.

In cases like this, it’s important to check back in — in a week, a month, six months, a year. It will take that long for all the dirt to come out about this Stanford study.

Update: How scientists spin the results of their studies.