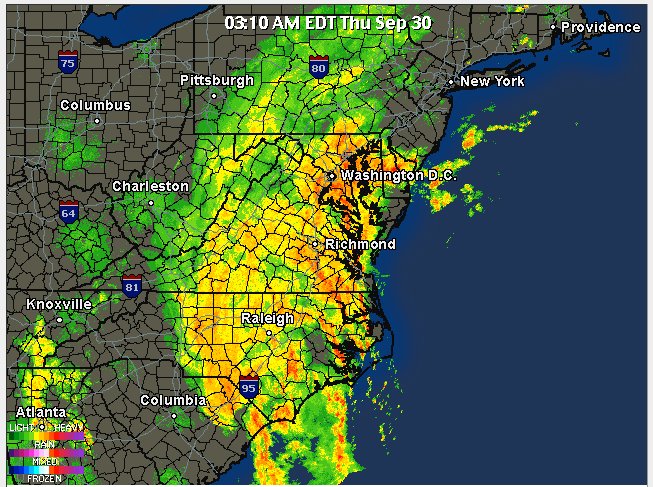

The gauge shows the 3.5 inches that fell last night.

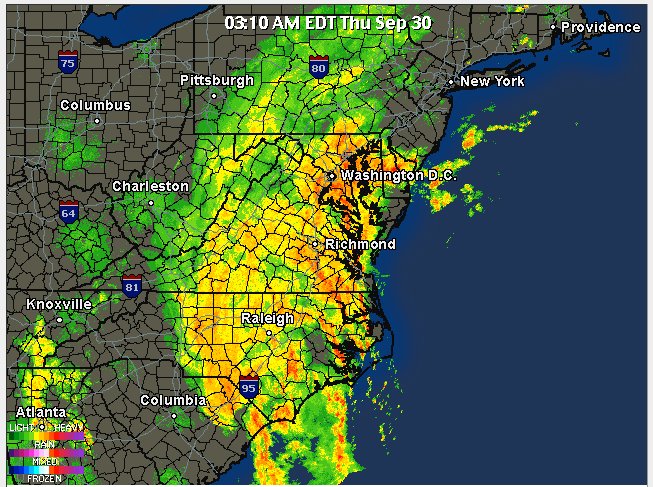

To me, few things are as disturbing as a drought. And few things make me feel more secure than the sound of water rushing in my little stream. I can hear the water now through the upstairs open window that faces the woods. The remnants of Tropical Storm Nicole just put an end to the drought that developed in North Carolina during a hot and dry September. A total of 6.2 inches has fallen here in the past few days. Areas to the east, closer to the Atlantic, had much more rain. Wilmington, on the coast, had almost 21 inches of rain from Nicole.

For those of us who want to turn our backs on the corporatized, consumerist lifestyle, few things are more important than water independence and water security. My goal is to live to be at least 100 years old. If I succeed at that, that’s almost 40 more years that Acorn Abbey will need to sustain me through global warming and economic and political changes that I’m probably not going to like. One of my daily reads is James Rawles’ SurvivalBlog.com. Rawles is a very intelligent and knowledgeable man, and his daily links are often very useful. But Rawles’ blog has a strong right-wing tilt. He still believes, because of right-wing ideology, that government, rather than out-of-control corporations and the corporate takeover of our government, is the problem. He’s very big on guns and defending one’s retreat as though it’s a fortress, though, to his credit, he also completely understands the necessity of sustainability. He sells his services as a consultant for people who are looking for retreats. He prefers the western United States, because of the sparseness of the population, weaker local government, and the prevailing winds carrying fallout if a big East Coast city was nuked.

I believe that’s all wrong, that some people’s ideology and too much Ayn Rand has led them to think that rugged individualism, hoarding, and lots of guns are the best defense against what may go wrong in the future. But the western states (with the exception of Idaho and a few other areas) are some of the most water-stressed parts of the country, and the water situation is going to get worse. Given a choice between guns and water, I’ll take the water.

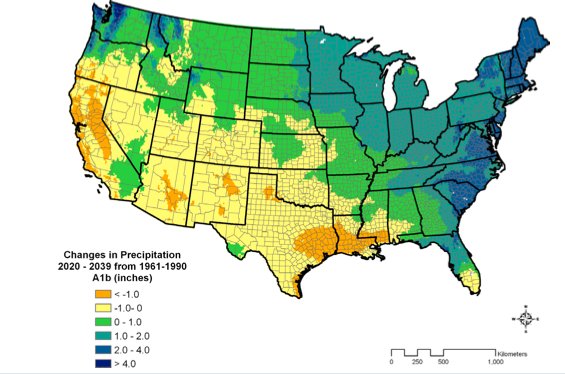

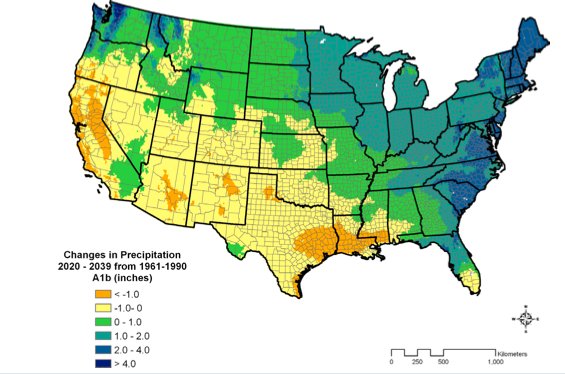

Before I finally made the decision to move back to North Carolina from California, one of the things I attempted to check was long-range projections for average rainfall in the face of global warming. I could find very little data in 2005, when I bought my land, though there seemed to be a consensus that hurricane-season storms off the Atlantic would be more common and more violent. Just this year, though, a research organization named Tetra Tech released a report combining projections from several different global warming models. They show this area of North Carolina gaining several inches of rainfall per year, on average. That is reassuring. One of the graphs from this report is at the bottom of this post.

In my attempts to model the future, it is silly to suppose that guns and hoards of food will get me through the next 40 years, should I be so lucky as to live that long. As I see it, sustainability is the key. Sustainability without rainfall and water is unimaginable. And though independence is a good thing, I also think it’s obvious that fortresses inhabited by rugged individualists with lots of guns are unsustainable.

What is sustainable, then? I think the answer to that is obvious, because that’s how it used to be done before we all became consumers in an economy in which people depend on corporations for everything. Farming communities are sustainable. To the right-wing mind, “community” is a dirty word that will always provoke a sneer. Even a very large farm is not likely to be completely self-sustaining. There are bound to be some things that one can’t produce and that one must trade for. When I was a child, I could hardly believe it when my mother used to tell me that, when she was a child, there was no such thing as a grocery store. A few times a year, she said, they’d buy flour, sugar and beans in 50-pound sacks. Everything else they grew. Those sacks, by the way, were often cotton muslin prints that could be made into clothing. I have a photo of my mother around age 16 in which I’m pretty sure the dress she’s wearing was made from a flour sack.

So, to me, picking a place for a retreat is not about totally getting away from people. It’s about getting into an area sparsely populated with the right kind of people. Those people are people who have tractors and fields and barns and pastures. Those people now go to the grocery store, for sure. But they have the option of going back to farming, and many of them still have the skills.

Acorn Abbey is a little less than 250 miles from the Atlantic. The North Carolina coastline sort of hangs out into the Atlantic. If you flew exactly east from Acorn Abbey, in about 250 miles you would come to the Atlantic around Duck, North Carolina. If you flew exactly south from Acorn Abbey, in about 250 miles you would come to the Atlantic around Charleston, South Carolina. This is good. Stokes County is far enough inland to be protected from the winds of a powerful hurricane. But the rain can get here in only a few hours.

Acorn Abbey’s water comes from a well. I have a small stream only a hundred feet downhill from the house, but that stream stops running in dry weather. The nearest stream that runs all year is about a hundred feet below my property line. The Dan River is two miles away. I could have done worse. But if there is one thing I could fix about Acorn Abbey, it would be this: I’d contrive to have some sort of reservoir of rain water that could be used to irrigate the garden. With limits, my well can do this. But the idea of using ground water for irrigation offends against my sense of sustainability. If there is a cost-effective way of impounding some rain water for summer irrigation, I will think of it.

This storm came straight off the Atlantic rather than from the Gulf.

Tetra Tech Inc. / National Resources Defense Council