Vintage Harris tweed jacket bought in Stornaway

The Scottish island of Harris is remote, windswept, rainswept, and underpopulated. How, then, did it become so famous? For Harris tweed, of course.

First, a technicality. The usual way to refer to this place in the Outer Hebrides is “the isle of Lewis and Harris.” That raises the question, are we talking about one island, or two? It’s actually one island. The northern part of the island is Lewis, and the southern part is Harris. Mountains form the geographical (and, to a surprising degree, cultural) boundary between the two places.

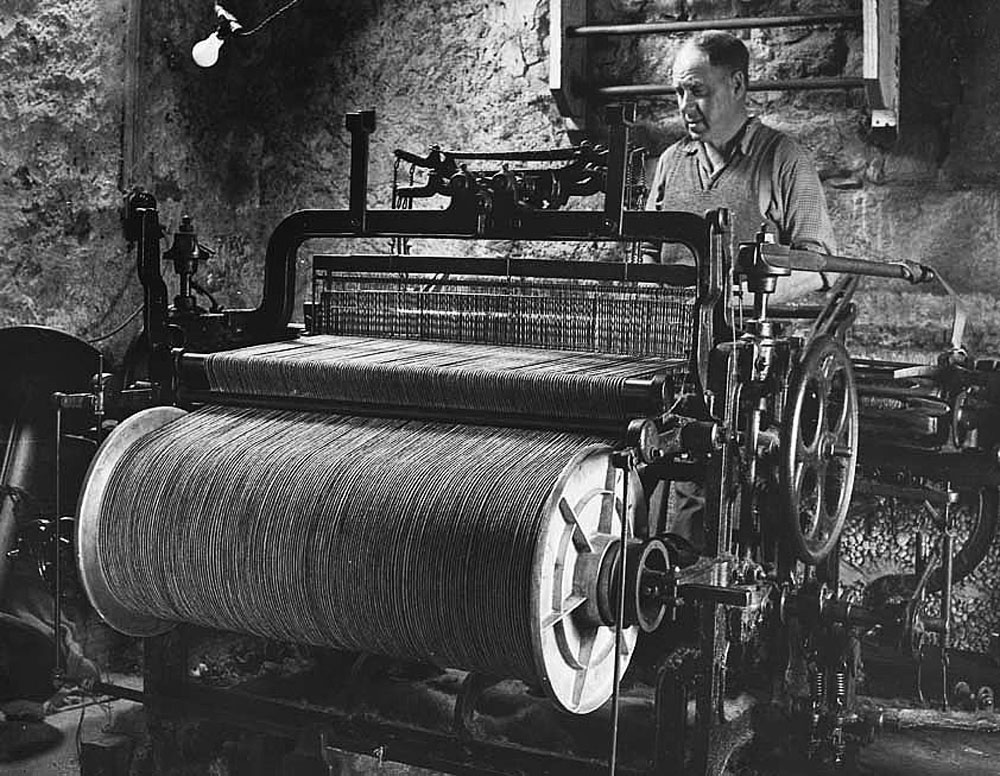

I have never particularly been interested in textiles. But what struck me about Harris tweed, as I learned more about it, is what an incredible model Harris tweed provides for a sustainable cottage-based industry. By law, Harris tweed comes only from these islands. All Harris tweed is woven by hand by the local crofters, at home in their cottages. (A croft is a small farm with its cottage and outbuildings.)

The production of Harris tweed peaked in 1966. But there are signs that it’s making a comeback, and production is expanding. The Wikipedia article gives a good brief history of Harris tweed. Crofters have been weaving it for their own use for centuries. In the 19th Century, it was discovered by the English aristocracy, and soon everybody wanted some. Everything came from the island’s own resources — wool from blackface sheep and dyes from wild local plants. Local mills spun the yarn. Once the cloth has been woven in the crofters’ cottages, the mills inspect, wash, and press the cloth.

I walked into a Harris tweed shop in Stornaway and was shocked at the prices. For handmade products of such quality, that is not surprising. Men’s jackets started at around £400 ($500). Even simple waistcoats started at about £140. I left the shop reluctantly, priced out of the market.

But fate stepped in. Upon returning to Stornaway some days later to catch a bus to the south of the island, a local man in a coffee shop struck up a conversation with me. He was wearing a Harris tweed jacket and waistcoat. After we had talked for a while, I complimented him on his jacket, saying that I’d love to have one but that the prices were just too steep. He told me where I might find a vintage jacket for much less. In fact, the shop was right nextdoor. In the shop I found a long rack of men’s jackets. The shop’s owner helped me try them on. The one I liked best fit me perfectly. The price was only £59, so of course I bought it. The cut is remarkably smart and modern, though the jacket was made in the 1960s or 1970s for Dunn & Company. The jacket is now at the cleaners, getting its buttons tightened up, along with a good cleaning and pressing.

To the men of this island (and elsewhere), where even in summer nighttime temperatures dip into the Fahrenheit 40s, a Harris tweed jacket is a year-round, everyday-casual item. I realized that, to be properly warm, the jacket should be worn with a waistcoat and scarf. I won’t hesitate to wear it to the grocery store this winter. I wore it to dinner at Oxford.

There’s a pretty good market for vintage Harris tweed items on eBay. I plan to look for a waistcoat there.

My post on Donegal tweed, September 2020.

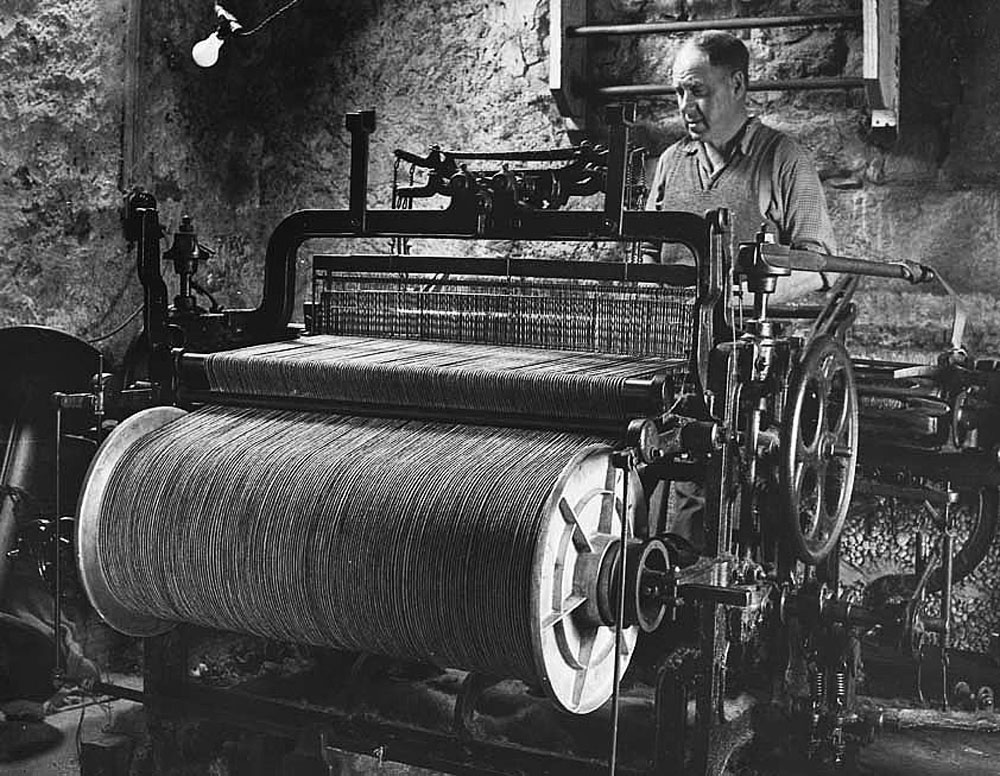

A Hattersley loom. It’s probable that my vintage jacket was woven on one of these. Wikipedia photo.

Blackface sheep near the village of Ardmor.

A crofter using a Hattersley loom, c. 1960. The weavers are men as often as women. Wikipedia photo.