Who We Are and How We Got Here. By David Reich. Oxford University Press, 2018. 368 pages.

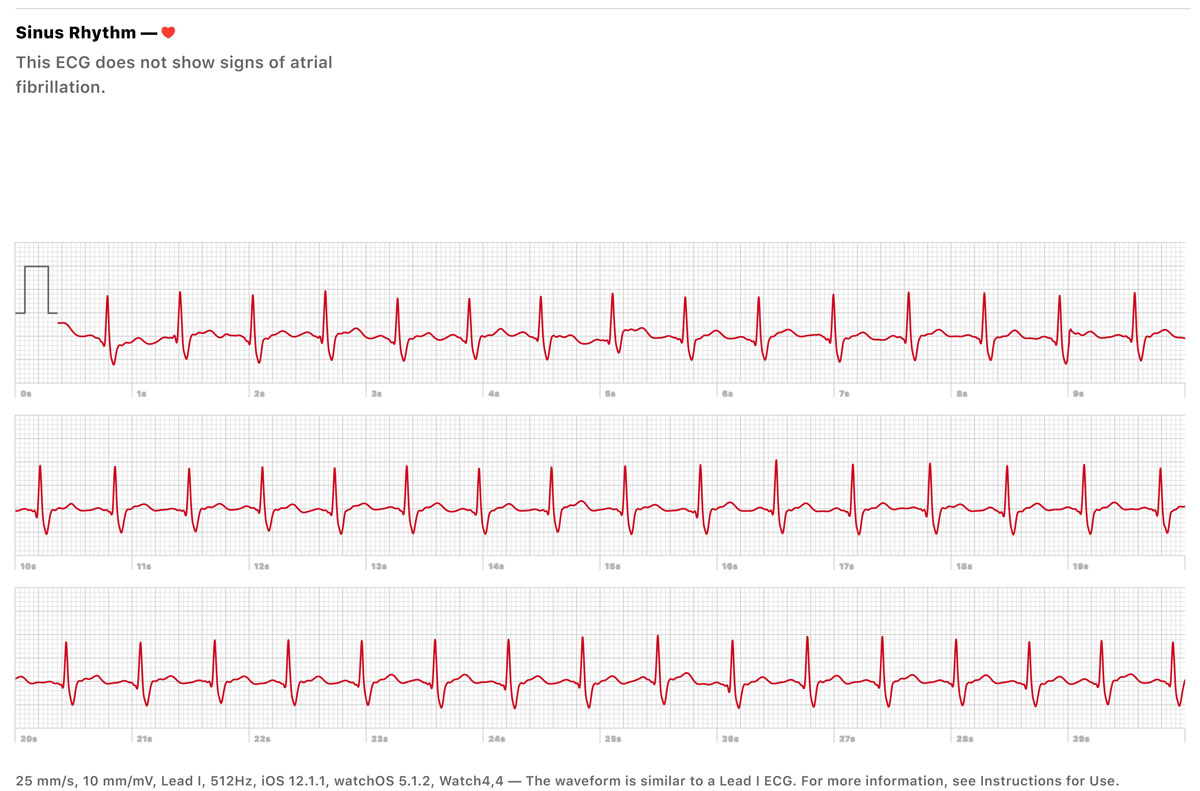

During the past ten years, gene sequencing machines have become available that are thousands of times cheaper to operate than earlier machines. The analysis of human genes can yield an astonishing amount of information about prehistory, an area that until fairly recently could be investigated only through archeology and linguistics. Using these new machines, labs such as David Reich’s lab at Harvard University have been extracting DNA from thousands of bones from all over the world that were contributed to the project by archeologists. New data is becoming available faster than it can be analyzed. The scientists doing this work are publishing papers too fast for even specialists to keep up with them all, and the papers are too technical for non-specialists to follow. David Reich’s book is one of the first, and few, books on this area of research for general readers.

In writing about this book, I first should confess that my interests are Eurocentric. My own Y-DNA shows that I am descended from Celts and that my paternal ancestors were almost certainly in Ireland centuries ago. In fact I have the genetic marker for descendants of Niall of the Nine Hostages, a semi-historical Irish king who seems to have left almost as many descendants as Genghis Khan. Reich actually mentions Niall of the Nine Hostages in this book as an example of inequality — how genetic research shows that powerful men were able to leave far more descendants than less powerful men. What is frustrating to me, though, is that when my Celtic ancestors first appear in history, it’s a history written by Romans, whose treatment of the Celts actually was a genocide in Gaul, and a cultural genocide elsewhere. The Celts make a brief and surely distorted appearance in ancient imperial histories, and then the trail goes cold.

Until geneticists got into the study of prehistory, our sources were archeology and linguistics. Those fields have done a remarkably good job of throwing a light on Iron Age and Neolithic prehistory in Europe. But many mysteries remained. Not long ago, I wrote here about two important works in this area — David W. Anthony’s The Horse, the Wheel, and Language; and The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World.

By merging what we have learned from genetics, archeology, and linguistics, we now have a pretty good overview of the migrations and innovations that shaped Europe. That story is of course too complicated to get into here. But briefly: The story of European prehistory goes back to the times when modern humans, as we call them, lived alongside Neanderthals, tens of thousands of years ago. In fact, many Europeans have up to 2 percent or a little less of Neanderthal genes. But it was the two most recent waves of migration that mostly made Europe what it is today. The first recent wave was about 10,000 years ago, as glaciers receded and Europe grew warmer. That wave of migration brought farming to Europe. The second wave was about 5,000 years ago. That wave brought the wheel, wagons, horses, and the Proto-Indo-European language. Europeans today are largely of two genetic haplotypes — R1a in the east, more toward Poland, and R1b in the west, peaking in Ireland and the west of Britain.

Though the archeologist Marija Gimbutas had found strong feminine influences in parts of Paleolithic and Neolithic Europe, there is strong evidence from genetics that the migration that brought the wheel to Europe was male-oriented, hierarchical, and often violent — little different from the Europe of recorded history into the 20th Century. Still, evidence is strong that, around 50,000 years ago, humans developed the capacity for complex behaviors and conceptual language. And here we are today, still struggling between enlightened and primitive behavior, cooperation and competition, caring and cruelty.

Though I am Eurocentric, David Reich is less so. There are interesting chapters on India, as well as Native Americans. And there is a fascinating chapter on inequality.

Reich’s book was not well received by some scholars. The book gets too close to hot-button issues such as racial differences or the lack of them, and the concerns of marginalized people. There are those who would shut down this kind of research. Reich’s book contains an extended argument for the necessity of accepting hard science, wherever it leads. There is no doubt that this area of research is being mined by thugs such as white supremacists. Reich very much acknowledges the projects of those thugs and shoots down many of their fallacies. But anyone interested in this area should be very wary in particular of what turns up in Google searches. It’s an area infested by crackpots who troll each other with crackpot theories.

So far, we have only scratched the surface of what we stand to learn. When I was halfway through this book, I already was feeling a frustration that no scholarship is available that seeks to connect written ancient history with what we know about prehistory from archeology, linguistics, and genetics. Near the end of this book, Reich clearly describes the work that needs to be done to write precisely that book. Many scholars are working in that direction. Within the next ten years, I expect such a book from — who else — the Oxford University Press.