Orson Scott Card, right. Source: Wikipedia

If you’re at all familiar with science fiction and with movies, then you know that Orson Scott Card is a controversial writer of science fiction who won both the Nebula and Hugo awards in 1985 for Ender’s Game. Ender’s Game has finally been made into a movie, and it will open Nov. 1, starring Harrison Ford and Asa Butterfield.

For years, Card wrote a weekly column for a small conservative newspaper in Greensboro, North Carolina. He frequently aired his controversial political views in the column, ensuring that he stayed in trouble with the literate intelligentsia, who don’t take kindly to right-wing thinking. That run of columns ended in April when the Rhino Times closed. But this month, the Rhino Times resumed publication with a new owner, and Card’s column is back. Here’s a link to his new column.

So far, Card has avoided controversy in the new column and has written mostly about food. No doubt the folks in Hollywood have asked him to avoid controversy, because some groups are already organizing boycotts of the movie version of Ender’s Game.

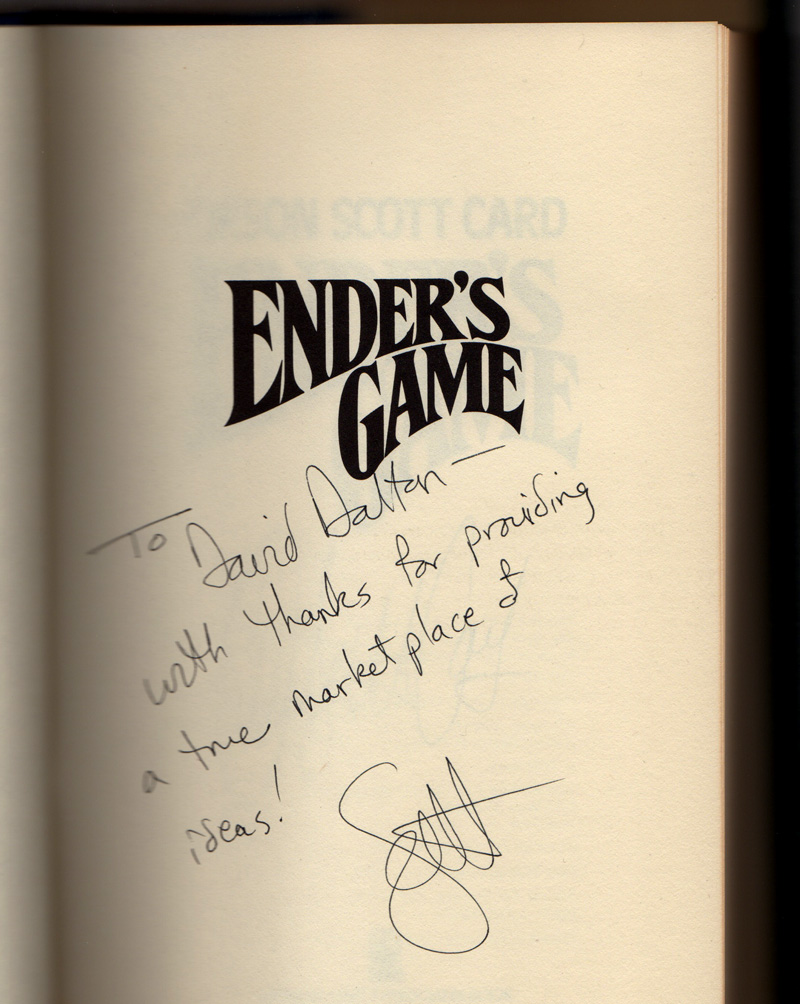

Though I totally don’t get Card’s politics, or his religion, I can’t be too hard on him. He’s an old friend, and we got to know each other back in the 1980s when I operated a computer bulletin board system named Science Fiction Writers Network. At the time, I was located near Winston-Salem, and Card was in Greensboro. So we were practically neighbors. I and some other local fans threw a big dinner for Card at a hotel in Greensboro to celebrate Ender’s Game winning the Nebula and Hugo awards. Also, Card was a guest for dinner at my place at least a couple of times.

Some other time, I’ll talk about the golden age of computer bulletin boards (early 1980s). I was in the thick of that golden age.

Anyway, I’m not going to criticize Card here. I still greatly respect his views on literature and storytelling. And because he influenced my own views so much many years ago, I’ve assimilated more than a little of Card’s literary DNA.

If you haven’t read Ender’s Game, it’s a classic. By all means read the book before you see the movie.

The title page from my autographed first edition of Ender’s Game