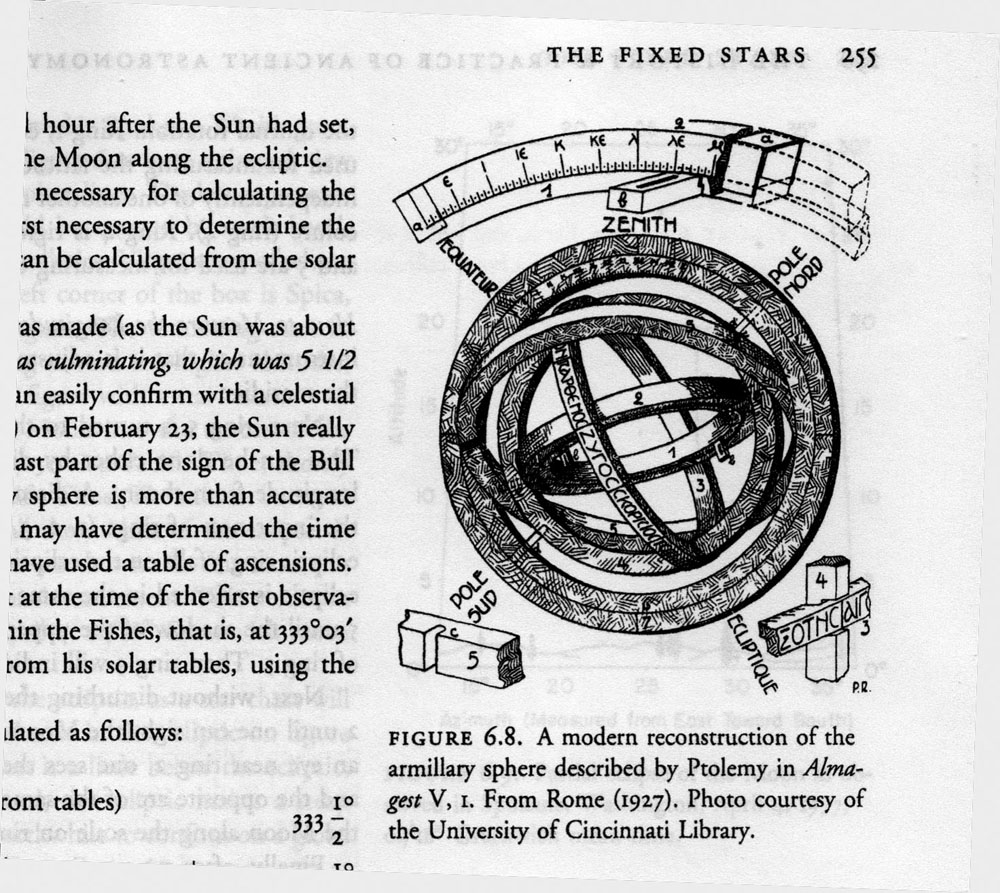

An illustration from James Evans’ book on ancient astronomy

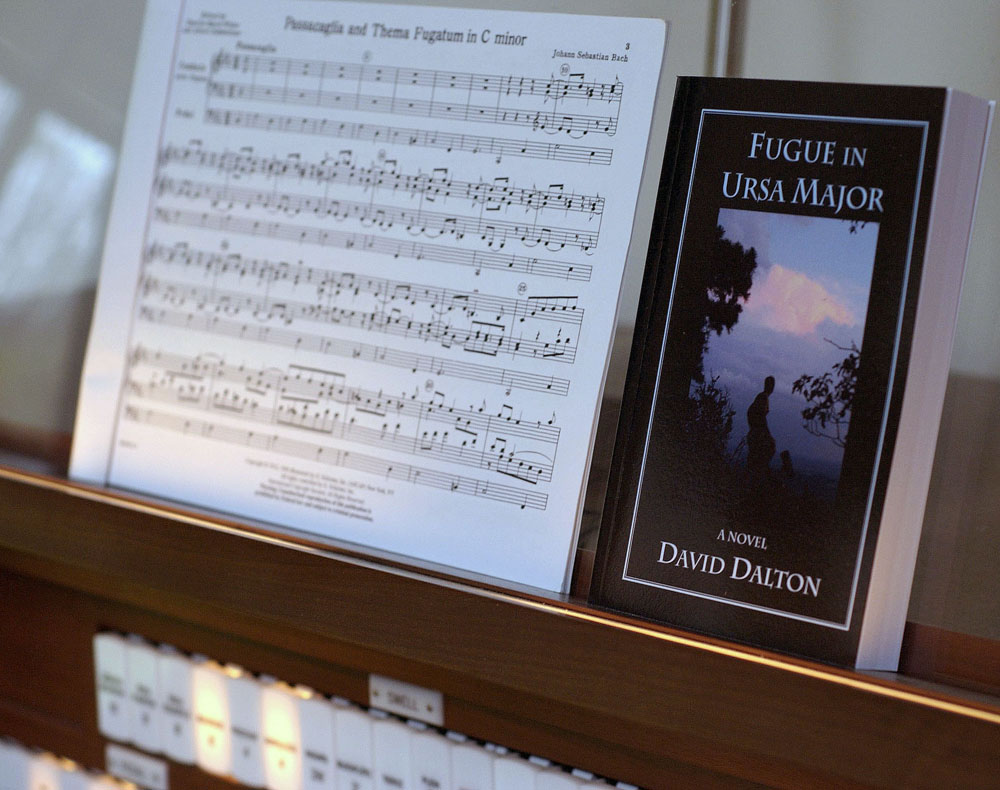

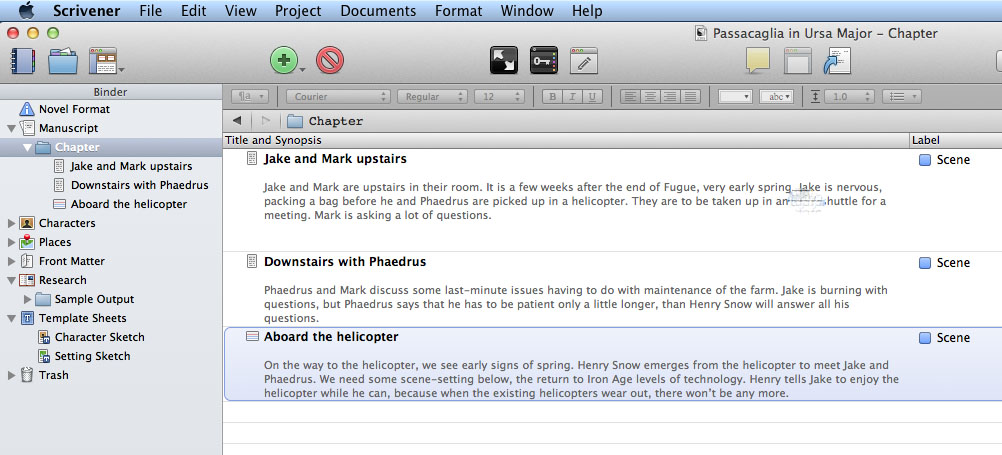

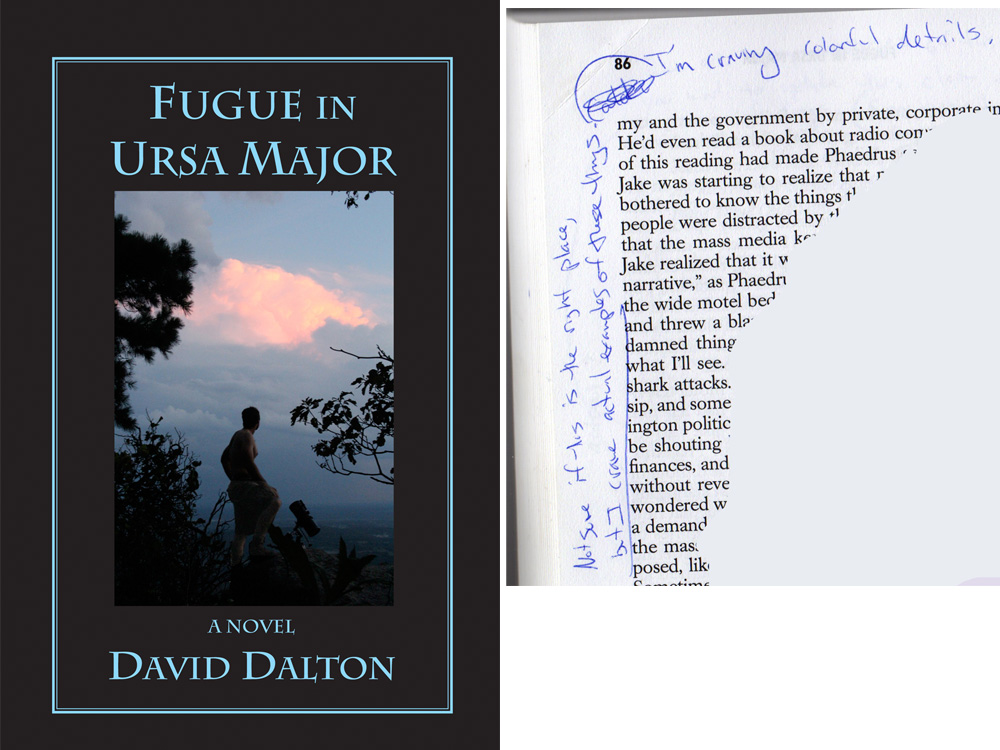

I’ve mentioned that the sequel to Fugue in Ursa Major is going to involve time travel. The plot requires that I have an understanding of the state of the science of astronomy around 48 B.C. As a source for that, I am reading James Evans’ The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy, which was published by the Oxford University Press in 1998. This is a beautiful, well-illustrated, and fairly expensive book. It has left me greatly impressed at just how much the ancients knew.

We generally assume that modern astronomy began with Copernicus and Galileo as the Dark Ages were coming to a close. In 1633, the church convicted Galileo for following Copernicus in saying that earth is not at the center of the universe. But some of the ancient Greek astronomers figured out that the earth moves around the sun, though it was not a mainstream idea in ancient times. Aristotle knew that the earth is a sphere. Heraclides of Pontos, a student of Plato, taught as early as 350 B.C. that the earth rotates and that the stars are fixed. Greek astronomers were able to make pretty good estimates of the size of the earth and moon, though their estimates of the size and distance of the sun were less accurate. The Greeks understood trigonometry. They had a pretty accurate theory of the motion of the planets. Even before the Greeks, the ancient Babylonians were excellent astronomers who made detailed star charts and kept accurate astronomical records. Babylon’s knowledge was passed down to the Greeks. The Greeks built on Babylonian astronomy, especially during the golden years of Alexandria, culminating with Ptolemy’s Almagest around 150 A.D. After Ptolemy, the Dark Ages began in the West, so Ptolemy remained authoritative for hundreds of years.

So, it’s not really true that, to the ancients, the science of astronomy was barely distinguishable from the myths of astrology. They knew a lot.

So how did they use what they knew?

For one, they wanted better calendars. The daily cycle, the lunar cycle, and the annual solar cycle don’t fit together in tidy ratios, so there is no perfect calendar. Our own Gregorian calendar, an antique which is a refinement of the ancients’ Julian calendar, requires all sorts of adjustments including leap seconds and leap years. In its essentials, our calendar today is the Roman calendar, which relied heavily on Greek astronomy.

Astronomy is critical to agriculture — when to plow, when to plant. This remains true today, and I still subscribe to an almanac, as did my grandparents. Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanac was a bestseller in the American colonies. People planted by it.

Astronomy also is critical to navigation, surveying, and mapmaking. Ancient sailors knew how to navigate by the stars. One of the reasons I chose Ursa Major as part of a book title was its importance to the ancients. The constellation of Ursa Major is visible for the entire year in most of the northern hemisphere. Ursa Major includes some easily identified “pointer stars” (the Big Dipper) that make it easy to locate the polar star and therefore true north. An ancient sailor who wanted to sail east at night would keep Ursa Major up to his left. We know that the ancient Celts had excellent seafaring skills and excellent ships and that the Celts also used Ursa Major for navigation.

How about astrology? It would be easy enough to accuse the ancients of being superstitious because they tried to use the stars to predict the future and to make generalizations about human nature and human fate. But we moderns are just as guilty, since horoscopes remain important in the lives of lots of people.

It’s easy enough to reproduce the astronomical observations of the ancients with some simple instruments. A gnomon (which is what a sundial is) will allow you to deduce and measure all sorts of information if you trace the sun’s shadow for a year. If you trace the sun’s shadow for a single day, you can very precisely locate true north. If you have a protractor or an astrolabe and measure the angle of the sun above the horizon on the summer solstice, you’ll know your latitude. Looking through tubes attached to a tripod will let you measure an object’s motion from hour to hour. You’ll need some star charts. And if you want to get fancy, you’ll need to brush up on what you learned about tangents, sines, and cosines in trigonometry class.

Even today, with an astrolabe, a watch, and a view of Ursa Major, you could throw away your GPS.

How would you do that? Measuring the angle of Polaris, the north star, above the horizon will tell you your latitude. That’s easy. Longitude is more difficult, and longitude bedeviled the ancients. But if you can determine your local time by getting a precise fix on noon (with the gnomon of a sundial, say, or the shadow of a stick stuck in the ground), and if you know what time it is at some distant place with a known longitude (Greenwich is handy for that), then you can calculate your longitude. At night, you can get a pretty good fix on the time by measuring the position of a known star.

To clarify the concept of longitude, keep in mind that the British navy carried accurate clocks on their ships (chronometers) not because they cared about the local time wherever they might be. Rather, the chronometer always said what time it was back in Greenwich. If you determine your local time from the sun or a star, then the difference between your local time and Greenwich time tells you how far you are east or west of Greenwich. After accurate clocks were available for ships, marine navigation greatly improved. This is why Britain’s Royal Observatory at Greenwich was commissioned by King Charles II in 1675. In the U.S., the Naval Observatory is one of the oldest scientific organizations in the country. The Naval Observatory was responsible for the “master clock” that the navy used for navigation. The observatory still is responsible for the master clock! The time used by GPS satellites is determined by the U.S. Naval Observatory.

But before GPS, if you were a ship at sea carrying Thomas Jefferson from Virginia to Calais, you’d needed a star to figure out the local time. The stars most convenient for that are in Ursa Major.

I like to think of it this way: The stars are still up there, raining information down on us day and night. All we have to do is just look up, and measure.