Barley biscuit, with potato in the dough

My quest for bread that is both truly good and truly healthy probably will go on for the rest of my life. Bread is probably my favorite food. I could live on San Francisco sourdough bread, Havarti cheese, wine, and strawberry preserves. Though I probably wouldn’t live for long.

A combination of barley flour and whole wheat flour (about four parts barley to one part wheat) makes a tasty biscuit or quick bread. Barley has a wonderful taste. But the bread is dry, with a mealy texture. Potatoes both moisten the bread and improve the texture.

Lately I’ve been cooking potatoes in advance and letting them chill before I use them. The chilling both improves the potato’s glycemic index and makes the potato a better food for the microbiome. Just mash the cooked potato into the bread dough.

⬆︎ Right side up on potassium

The daily requirement for potassium is shockingly high. Most people, it seems, are deficient in potassium. In fact, many people probably get more daily sodium than potassium. That would be “upside down on potassium,” which is not at all a healthy thing.

Low-sodium V8 juice is nice way to get some potassium insurance. It’s supplemented with potassium chloride, though the vegetable juices are naturally high in potassium. Per cup, it has 850mg of potassium, 140mg of sodium, and 45 calories. That’s a good deal, nutritionally. I also find that V8 juice helps me cut down on wine consumption, because V8 juice goes very nicely with meals.

Fried oysters — from the Chesapeake Bay

⬆︎ Trucked in and fried

Once or twice a year, I get an irresistible craving for fried oysters. Here in the American South, at least within easy trucking distance from the coast, the art of frying seafood is extremely well understood. Any town of any size will have a fried fish house.

I’m in North Carolina. North Carolina does produce some oysters, but most of our oysters here come from the Chesapeake Bay. Last year, the Chesapeake Bay in Virginia and Maryland had the biggest oyster harvest in 35 years:

“The Chesapeake oyster is still in the very early stages of a comeback after a tremendous amount of investment in reducing pollution to the Bay, years of diligent fishery management, and significant successful state and federal investment in oyster restoration. To keep oyster numbers growing, harvest increases must continue to be done slowly, incrementally, and cautiously, as VMRC staff recommends.”

I never appreciated just how vast the Chesapeake Bay is, and how much coastline it has, until I flew over the full length of it, north to south, on a flight from New York to Greensboro. Such flights normally would take a more westerly course over land. But on that particular day, a line of inland thunderstorms pushed air traffic east. It’s good to hear that the Chesapeake Bay — a classic commons — is making a comeback after years of abuse. We understand very well now that a commons must be regulated, or it will be abused and depleted.

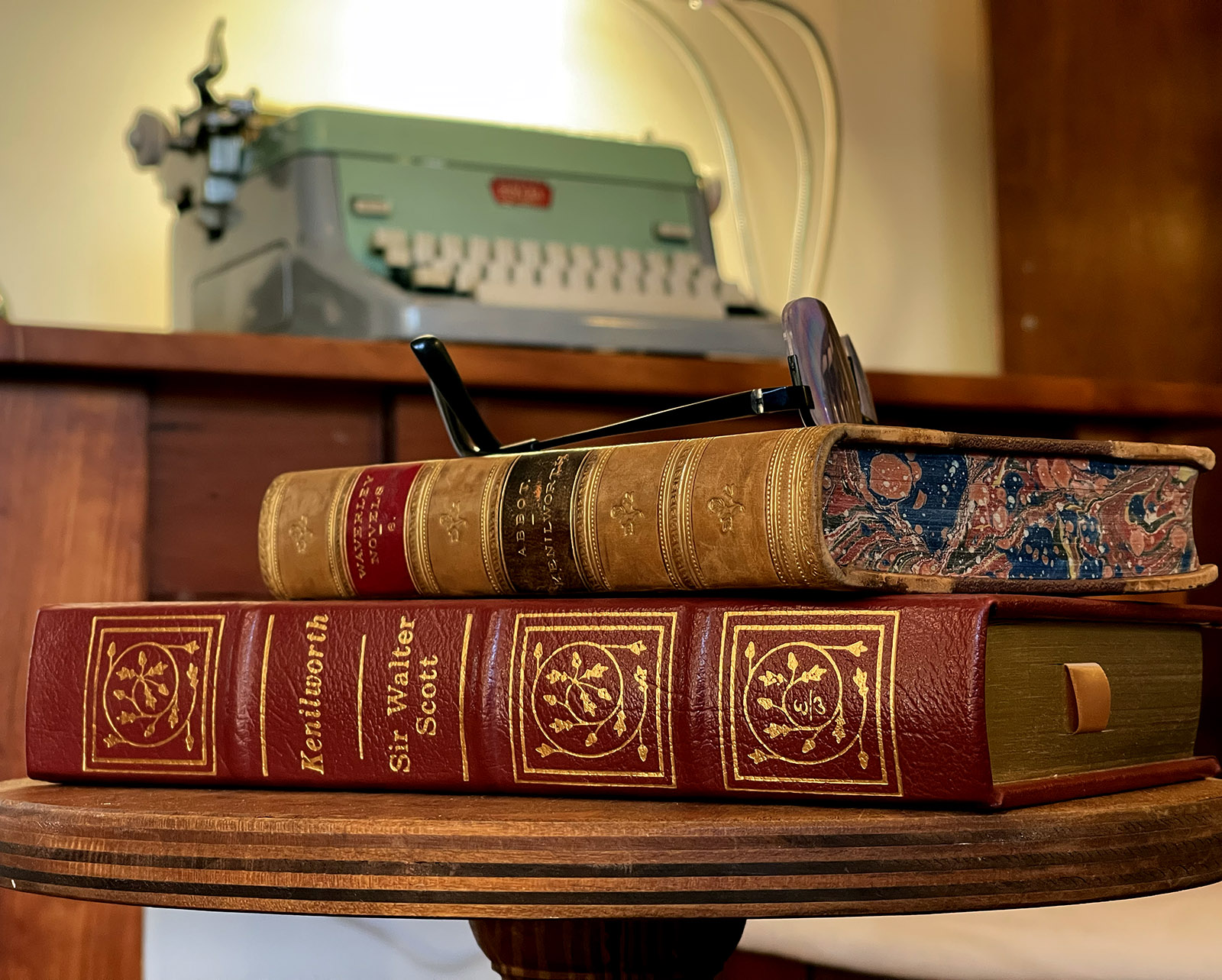

Daffodil shoots

⬆︎ February. What a relief.

Everybody I know, no matter where they live, said that January was miserable. Now that February is here, things are looking up. The daffodils should be blooming here in a couple of weeks.

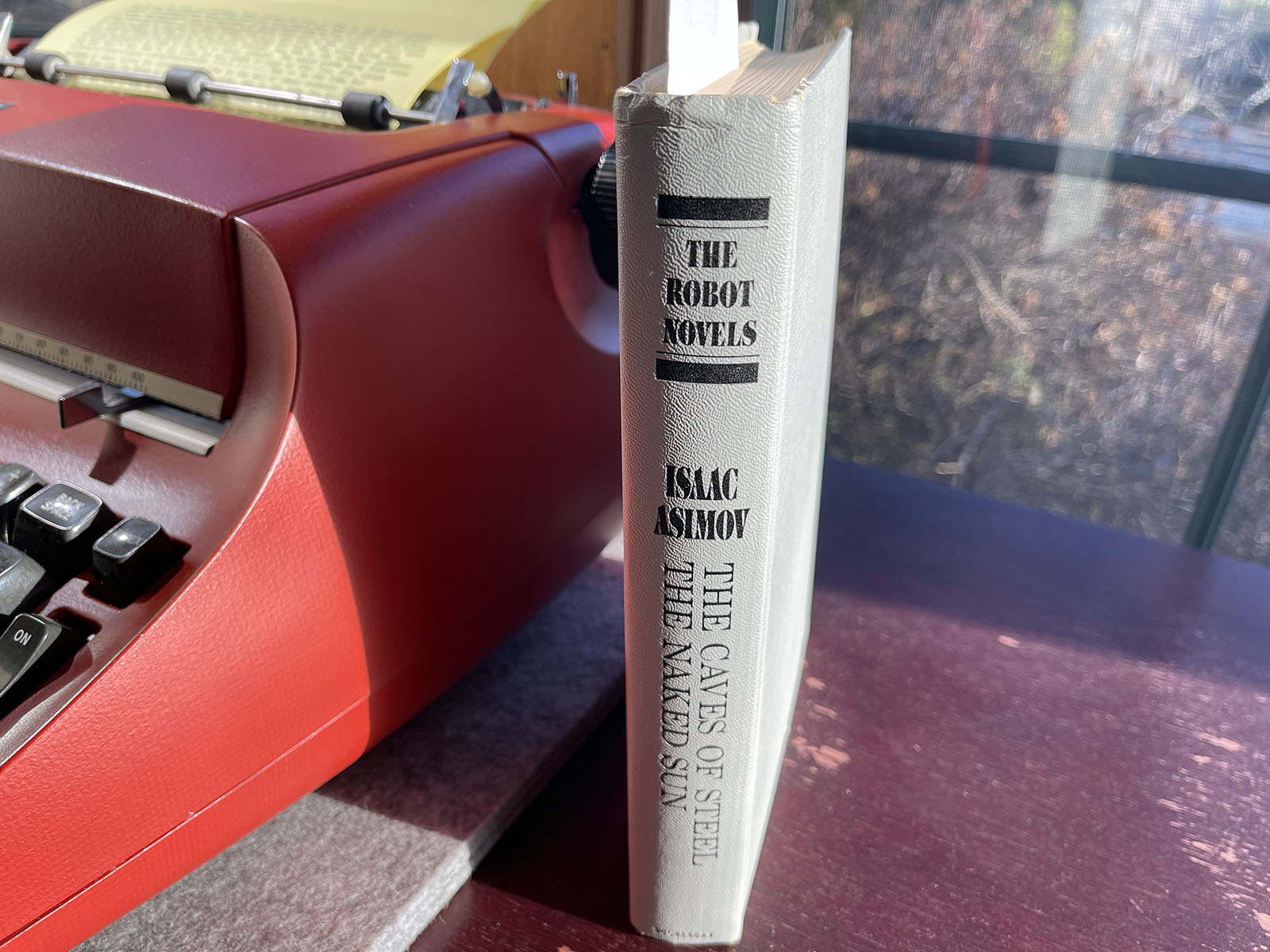

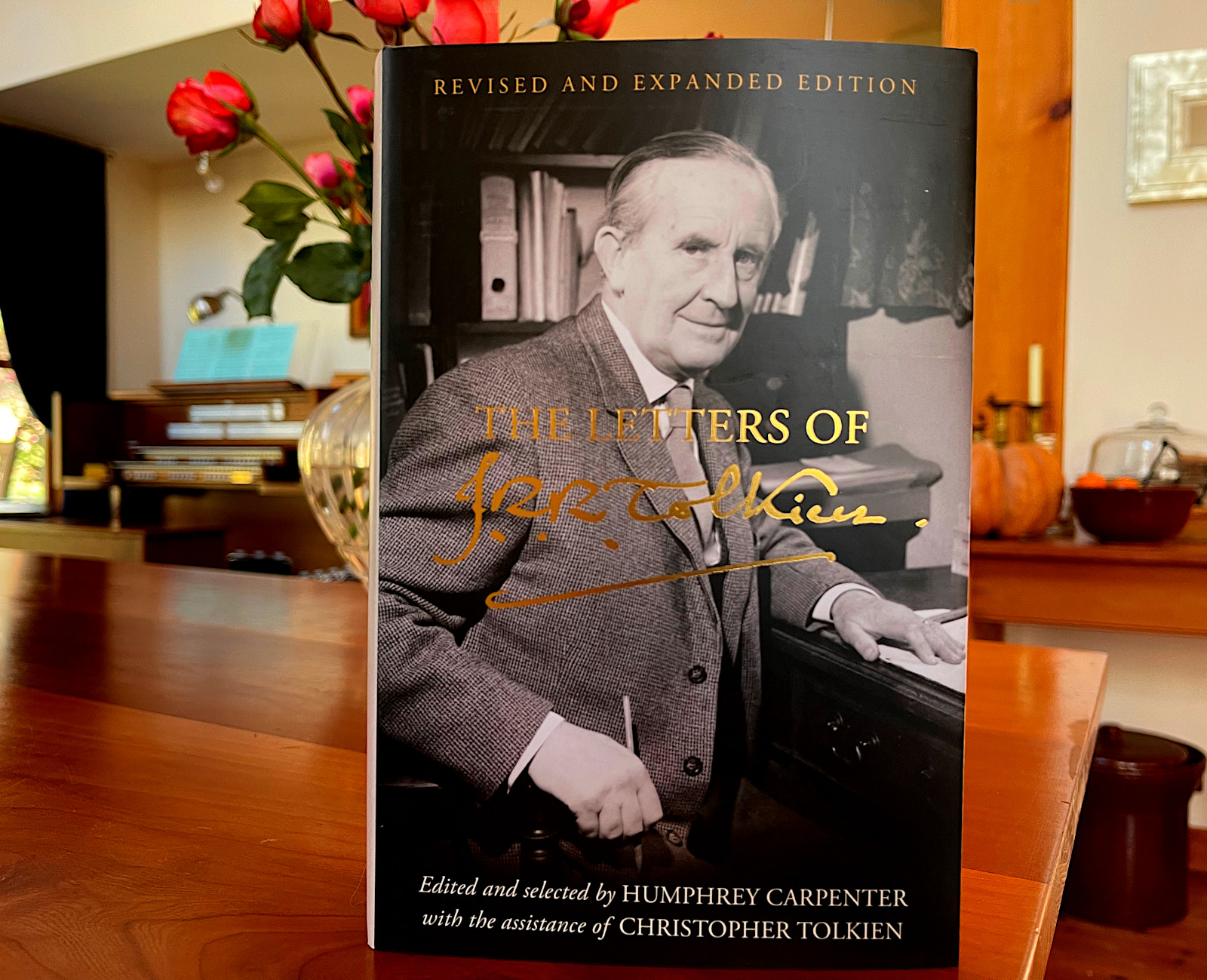

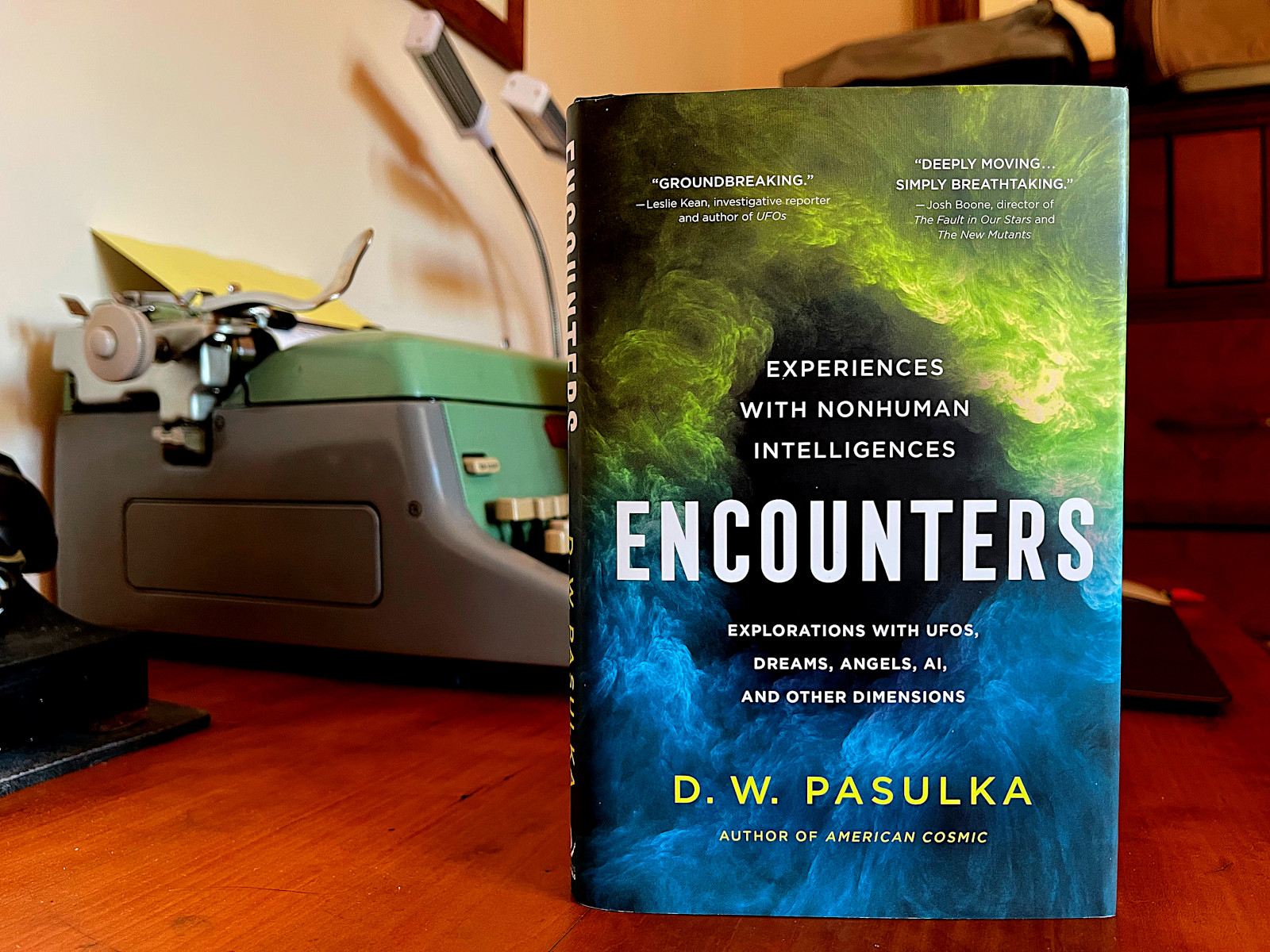

⬆︎ Asimov’s robot novels

The first of Isaac Asimov’s robot novels, The Caves of Steel, was first published in book form in 1954. I had wanted to read it as escape fiction, but I’m afraid it must now be read as historical fiction. The plot is so-so, and the anticipation of the future misses the mark. It’s really just a murder mystery set in the future. But the writing is good.

I bought both The Caves of Steel and The Naked Sun (which is the second robot novel) in a hardback book club edition that I think was published around 1961.

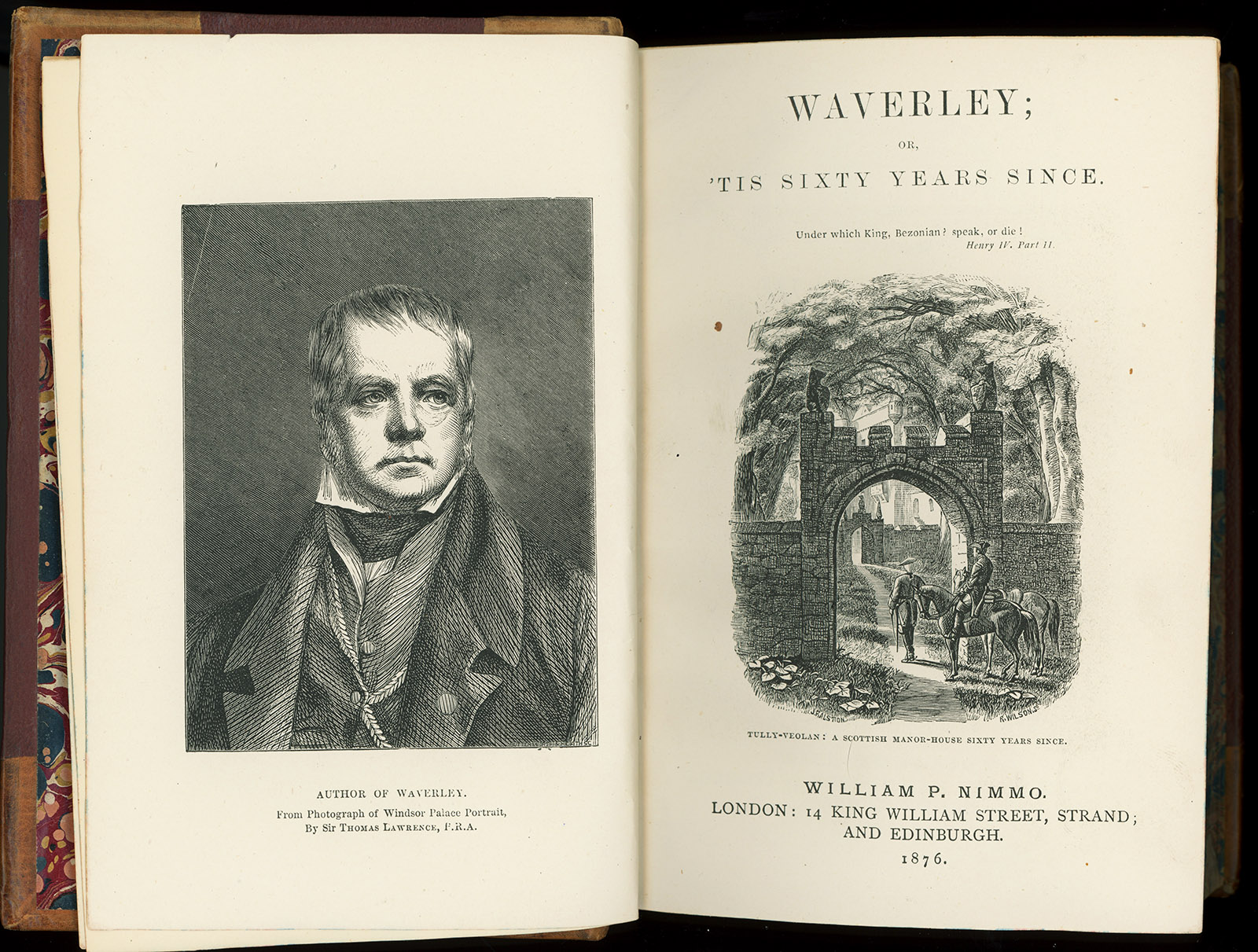

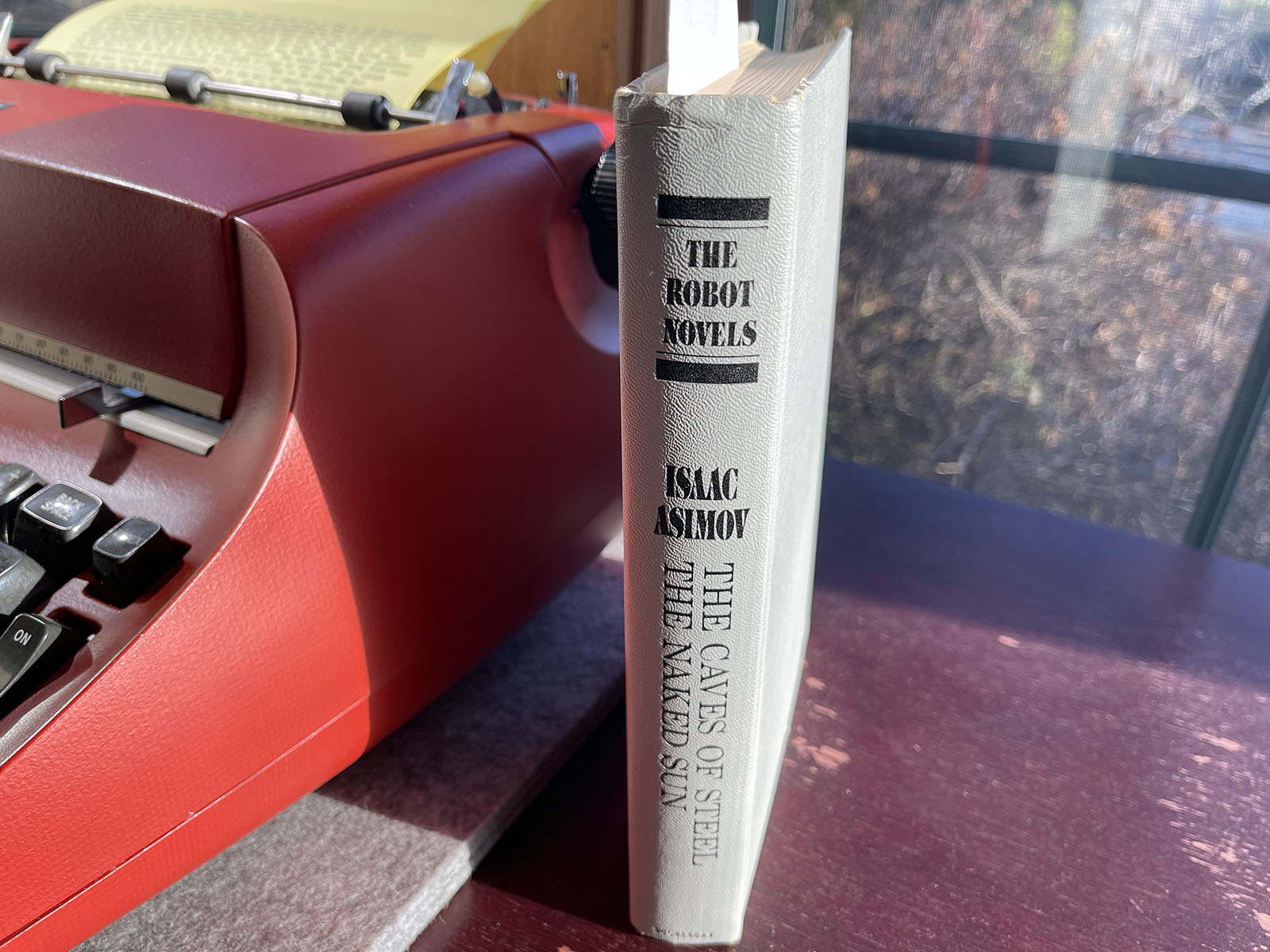

⬆︎ The extended editions

I’m finding that I like the extended versions of The Lord of the Rings films better than the theater versions. The scenes that were cut from the theater versions clearly were cut to reduce the run time, not because the scenes that were cut were inferior. The restored scenes include a lot of beautiful dialogue straight from Tolkien and a lot of excellent character development.

The extended versions can be streamed from HBO Max.

From a neighbor’s game camera

⬆︎ There are now two white deer in these woods

The oldest white deer in the woods here is at least eight years old, because it was eight years ago that I first got a photograph of her. There have been rumors of a second white deer for quite some time. But only a week or so ago did a neighbor get proof of it on a game camera. There are two white deer in the same frame. One is smaller and may be a yearling.

White Girl, in my driveway, three days ago, shot from an upstairs window. It was odd, but just before White Girl was in the driveway, a red fox was standing in the same spot, then scampered into the woods. I asked a neighbor, who has lots of game cameras and who has given names to a lot of the wild critters, whether the deer and the fox are friends. “I think they just use the same trails,” he said.