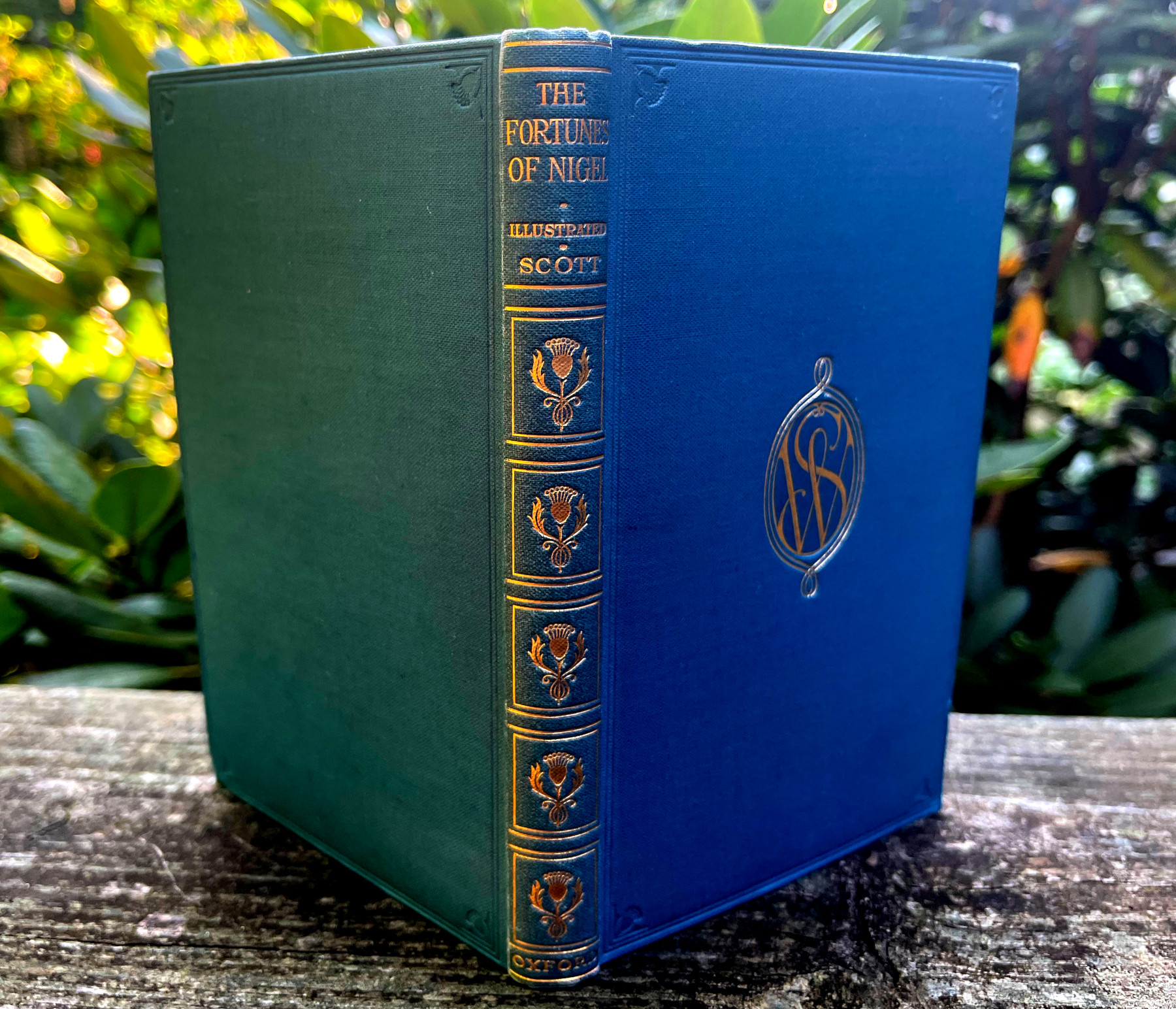

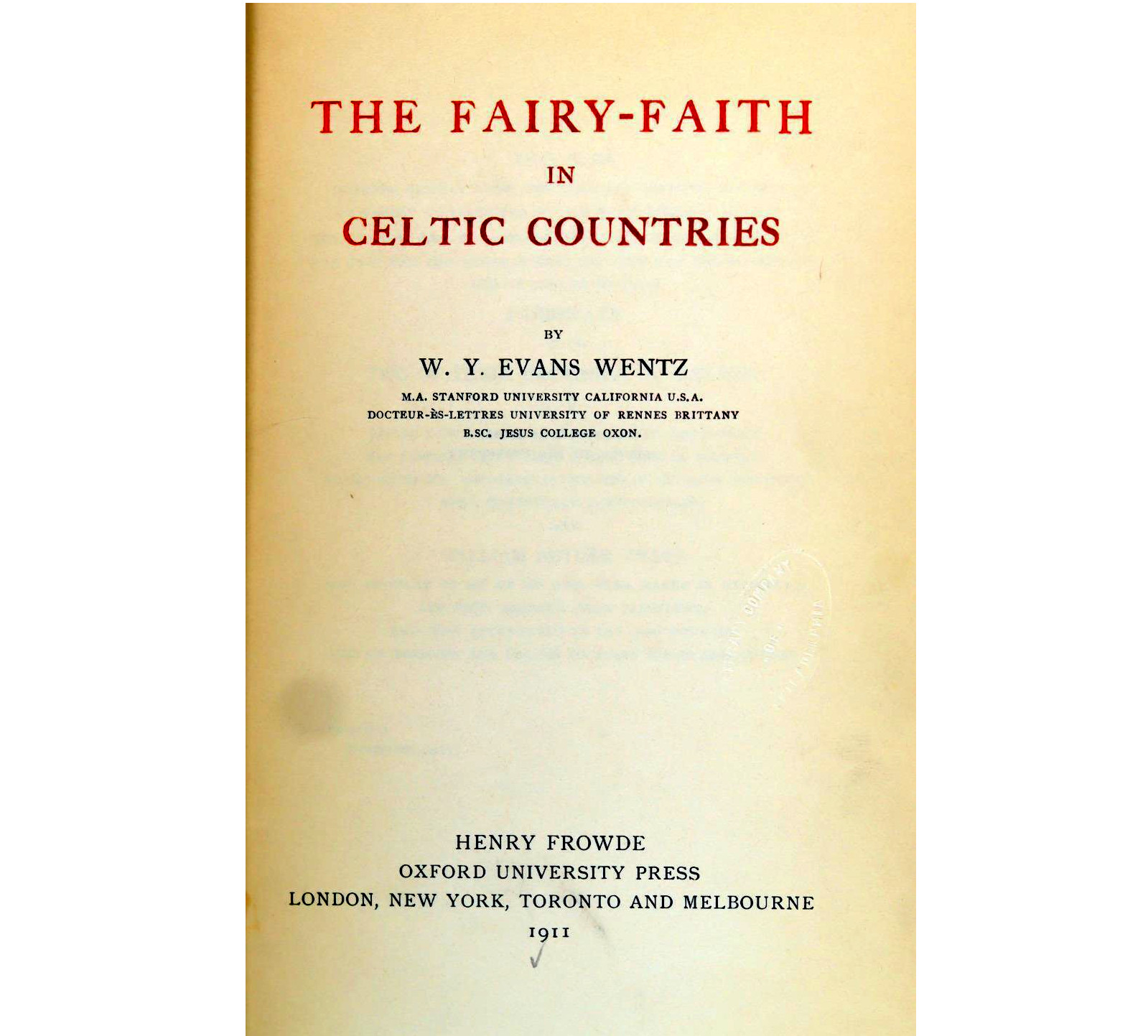

The injured book

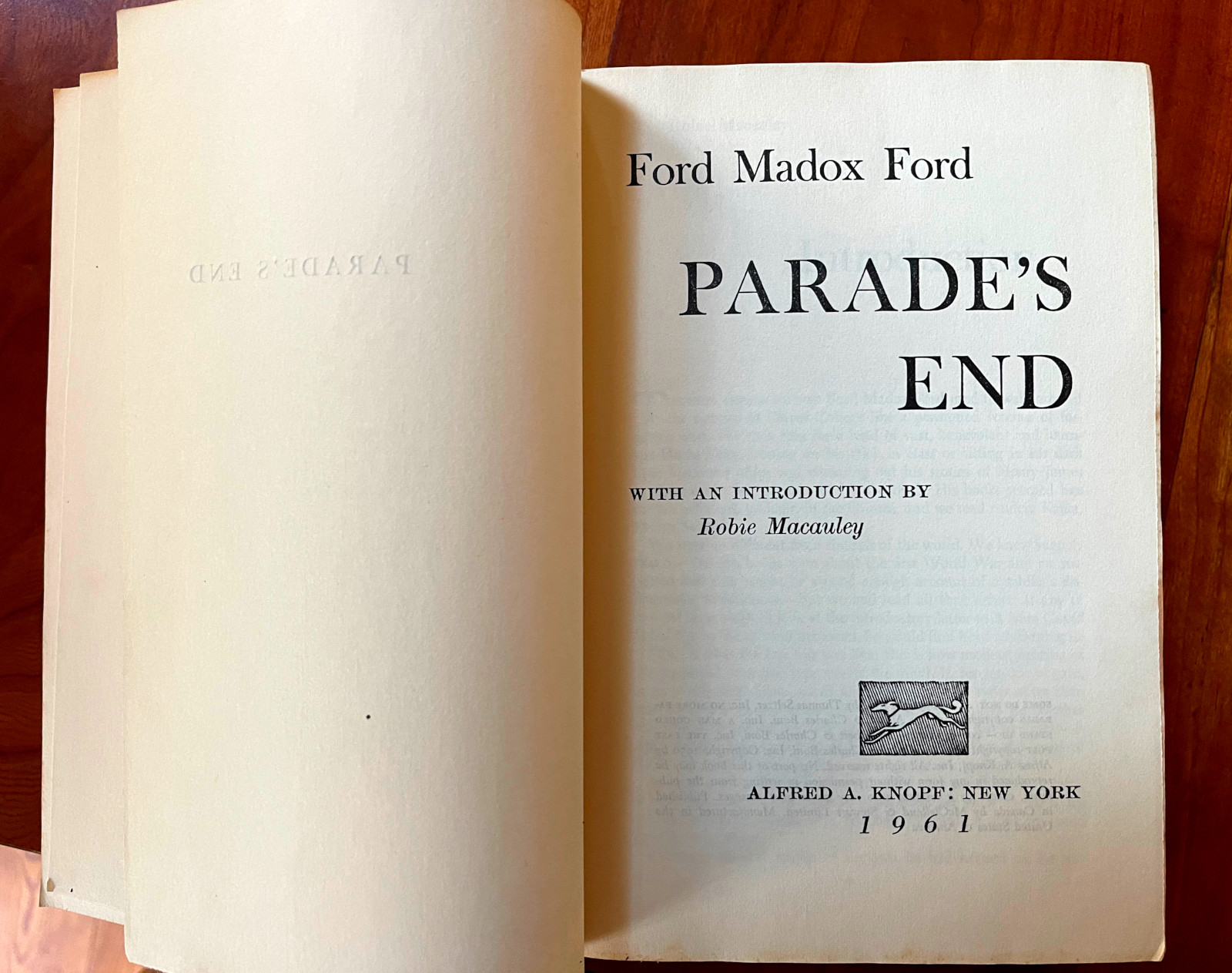

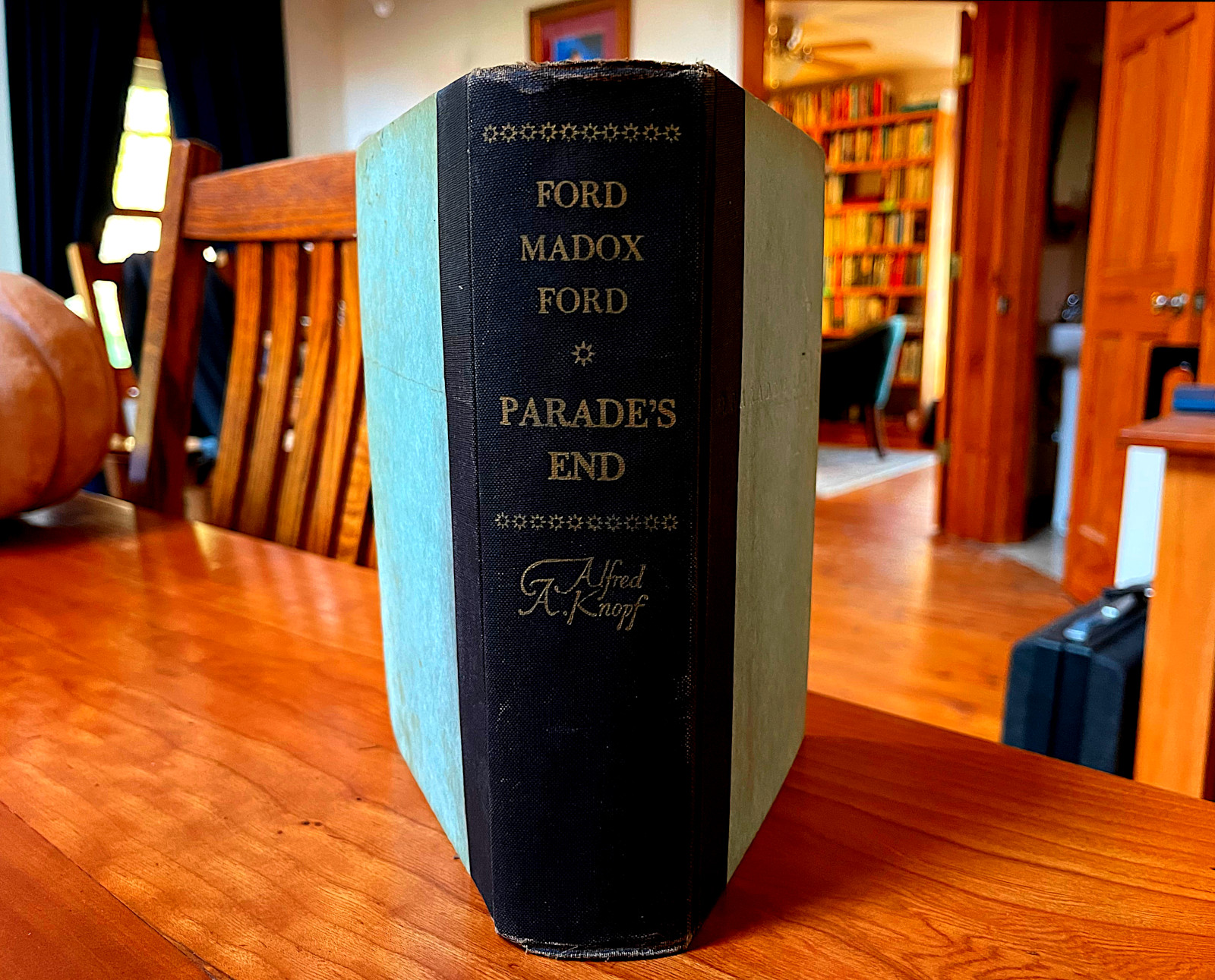

A few days ago, I mentioned here that I am very enthusiastic about a five-part BBC series from 2012, Parade’s End. (The series can be streamed on HBO Max.) The series is visually beautiful, perfectly cast, and brilliantly written, with some of the best dialogue I’ve ever encountered. I don’t yet know to what degree the perfect dialogue should be attributed to Tom Stoppard, who adapted the novels and wrote the screenplay, or to the author of the novels, Ford Madox Ford, who published the novels between 1924 and 1928. I had not heard of Ford Madox Ford, but I was determined to explore the novels. First editions of these novels are rare, but I found a 1961 revival edition on eBay. This edition contains all four novels in a single volume, at a hefty 838 pages. My guess is that even this 1961 edition is not common.

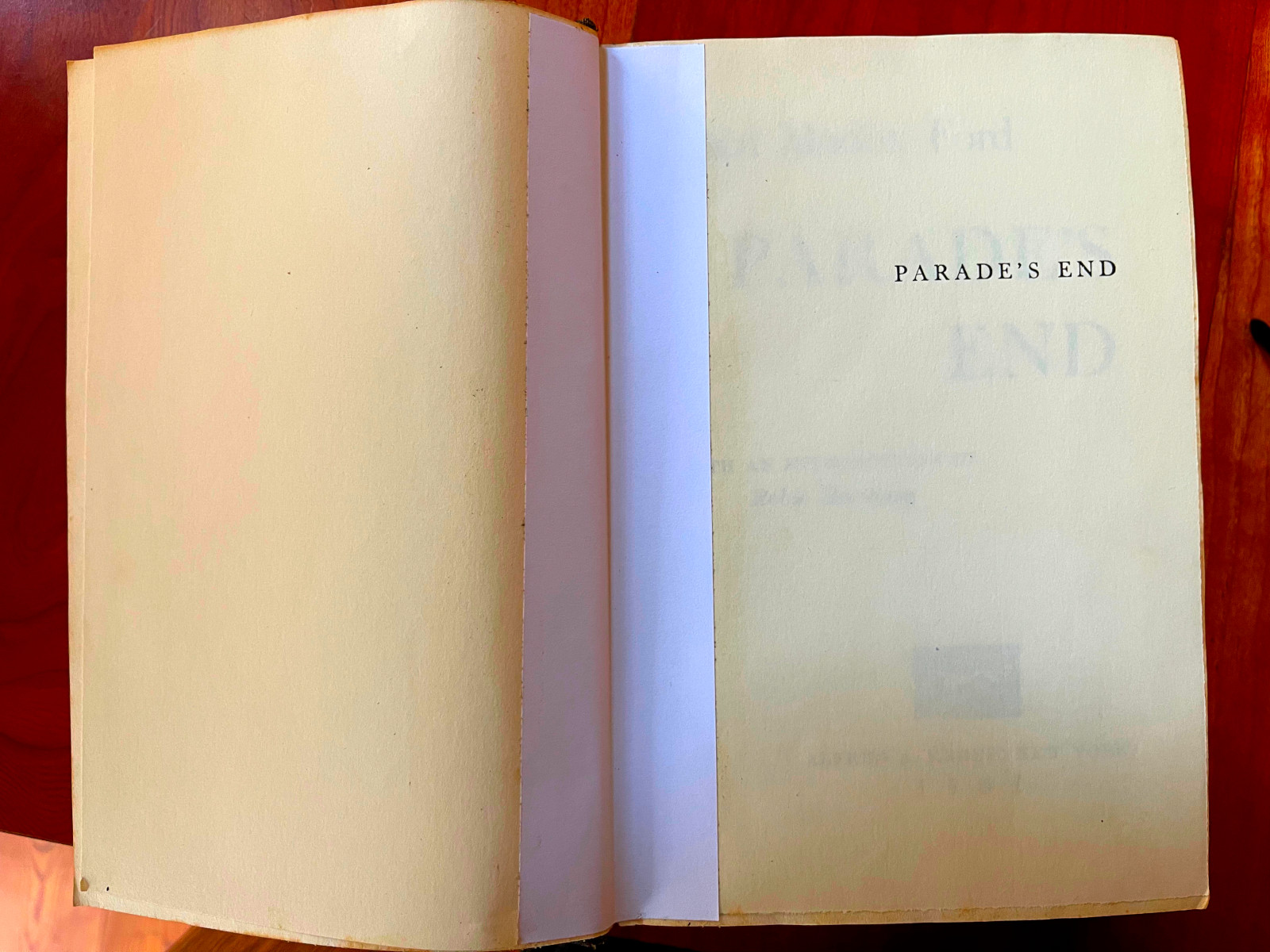

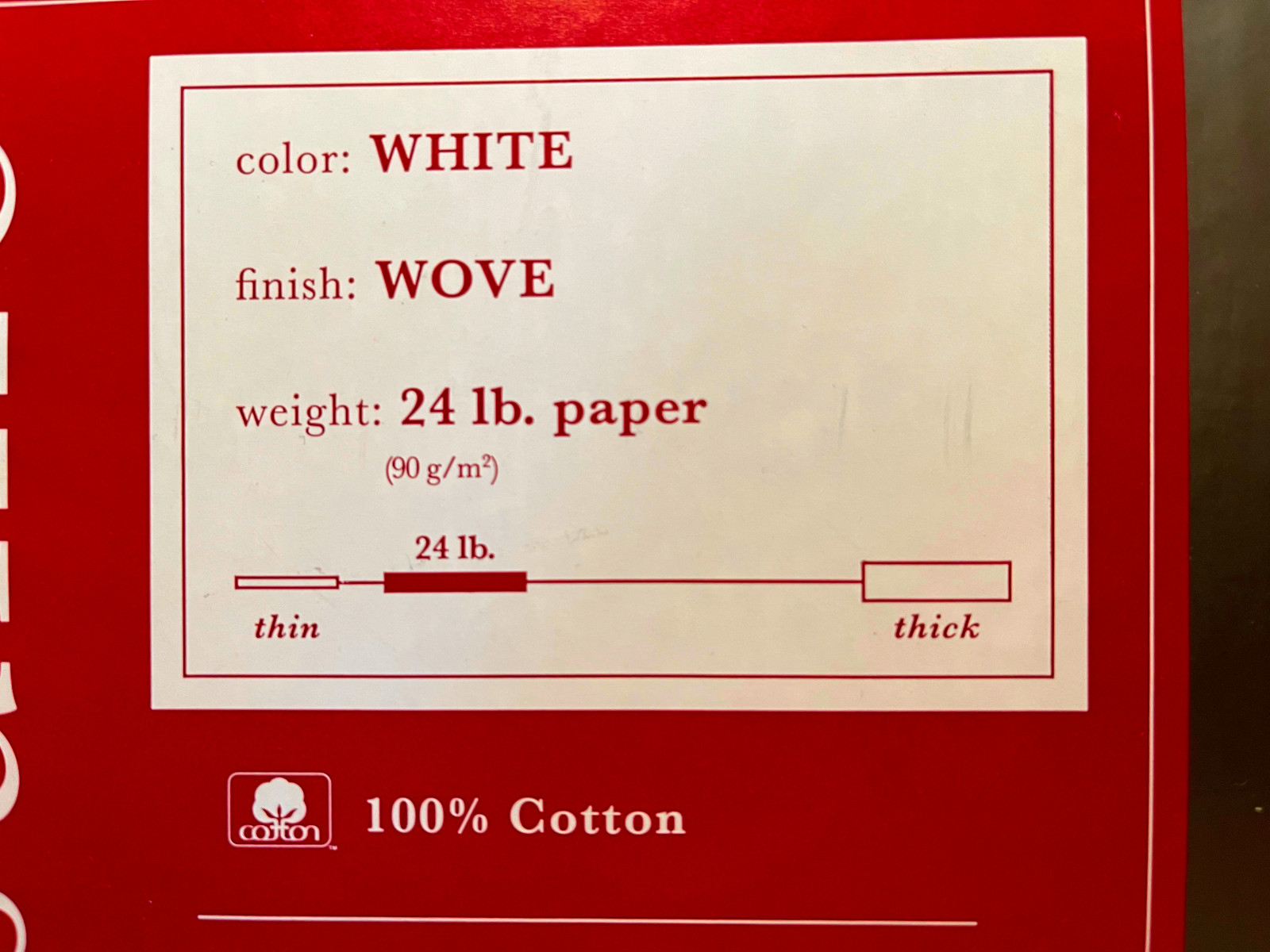

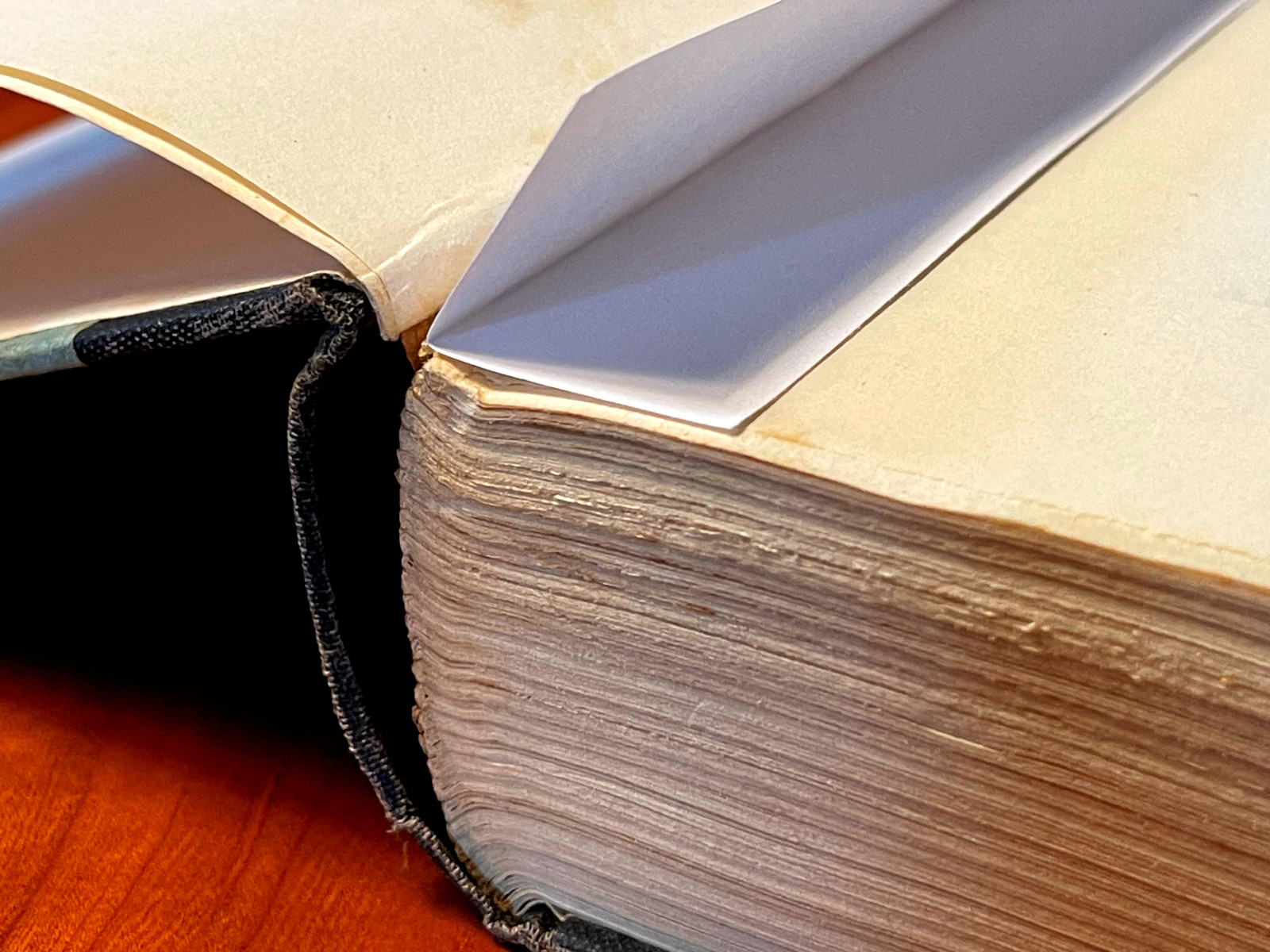

When the book arrived, I was sad to see that it had been injured. The front end paper was broken at the hinge, exposing the innards of the binding. No doubt librarians have a standard method of repairing such injuries, but I had to make up my own solution. That was to cut a strip of strong paper and glue it in with rubber cement to close up the rip in the end paper. That worked great. Books with lots of pages are particularly vulnerable to this kind of damage. I can’t help but wonder what happened to the book. Some previous owner clearly understood the book’s historical value, because inserted under the back cover was a printout of an article about Ford Madox Ford from the September 17, 1950, issue of the New York Times Book Review.

Ford Madox Ford

The 1950 article from the New York Times Book Review can be read here but requires a subscription to the New York Times. The article is “The Story of Ford Madox Ford: In Parade’s End a Master Novelist Caught the Essence of His Generation.” The article was written by Caroline Gordon, who I now see represents some literary history that I need to explore, including a connection to my native state of North Carolina. Here is the article’s first paragraph:

In 1938 Ford Madox Ford made a talk before a class of girls who were studying “the novel” under my tutelage. It was in April. In North Carolina. April in North Carolina is like July in less-favored climates. Ford was then in his early sixties and already suffering from the heart disease that killed him; he seemed to feel the heat even more than we had feared that he would. My husband and I debated as to whether it would be safe to let the old man make the talk he was bent on making. When we reached the classroom the next morning and I saw that his veined, rubicund face had gone ashen from the effort of climbing the stairs I wished that I had not accepted his offer to speak. He sat down at one end of a long table, his chair pushed well back in order to accommodate his great paunch, his legs spread wide to support his great weight.

Also:

It is easy to see why Ford’s work was not popular in his own day, but it is hard to see why it has been neglected in our own, for he would seem, in these times, to have a special claim on our attention. He is a superb historical novelist, seeming as much at home in a medieval castle or in Tudor England as in Tietjen’s twentieth-century railway carriage.

I am not yet certain what Caroline Gordon’s connection to North Carolina was, but I suspect it was the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

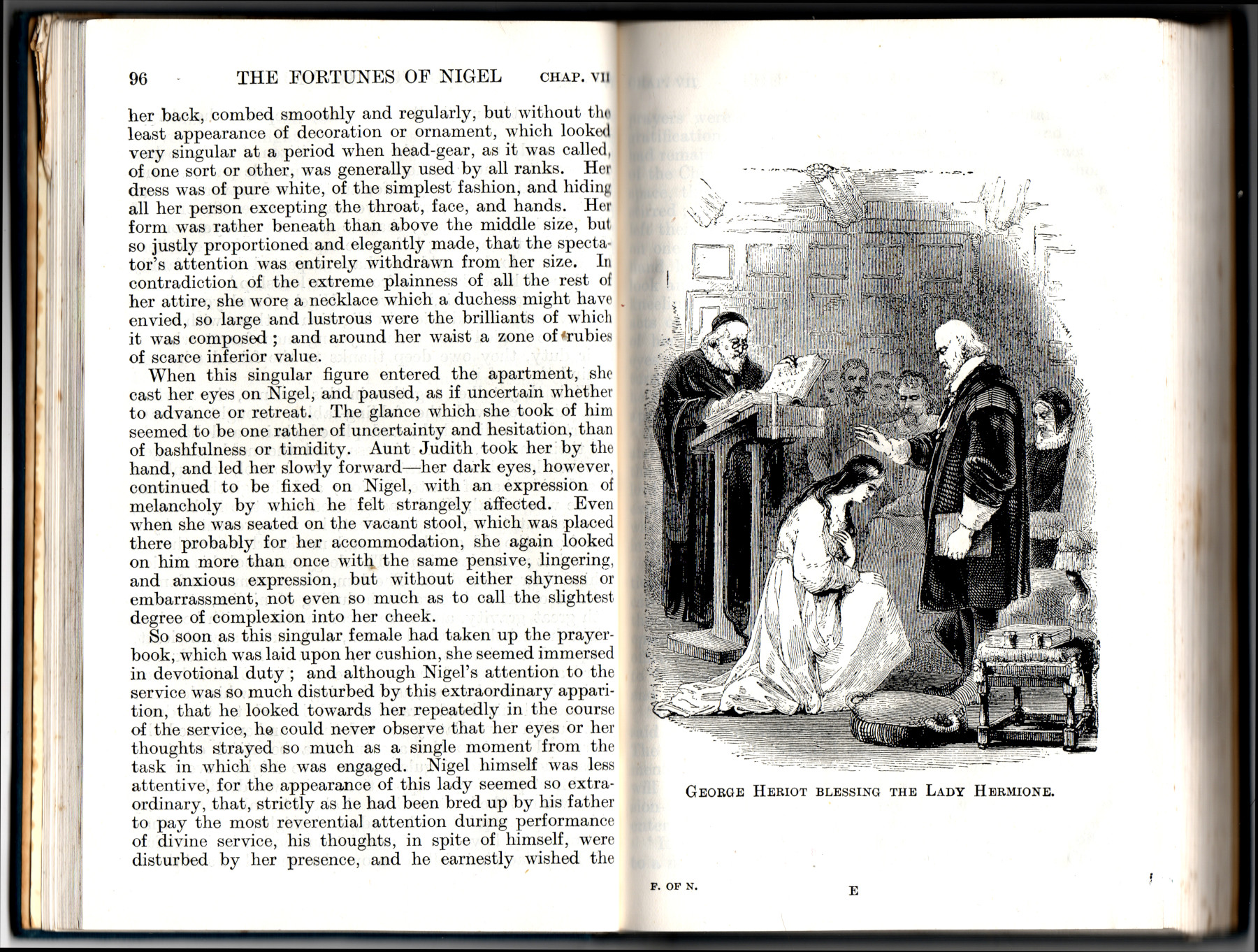

I am hoping that I will like Parade’s End and that Ford’s novels — as long as I can find copies of them — will be as rich a mine of literary history as I have found in the also-neglected historical novels of Sir Walter Scott.