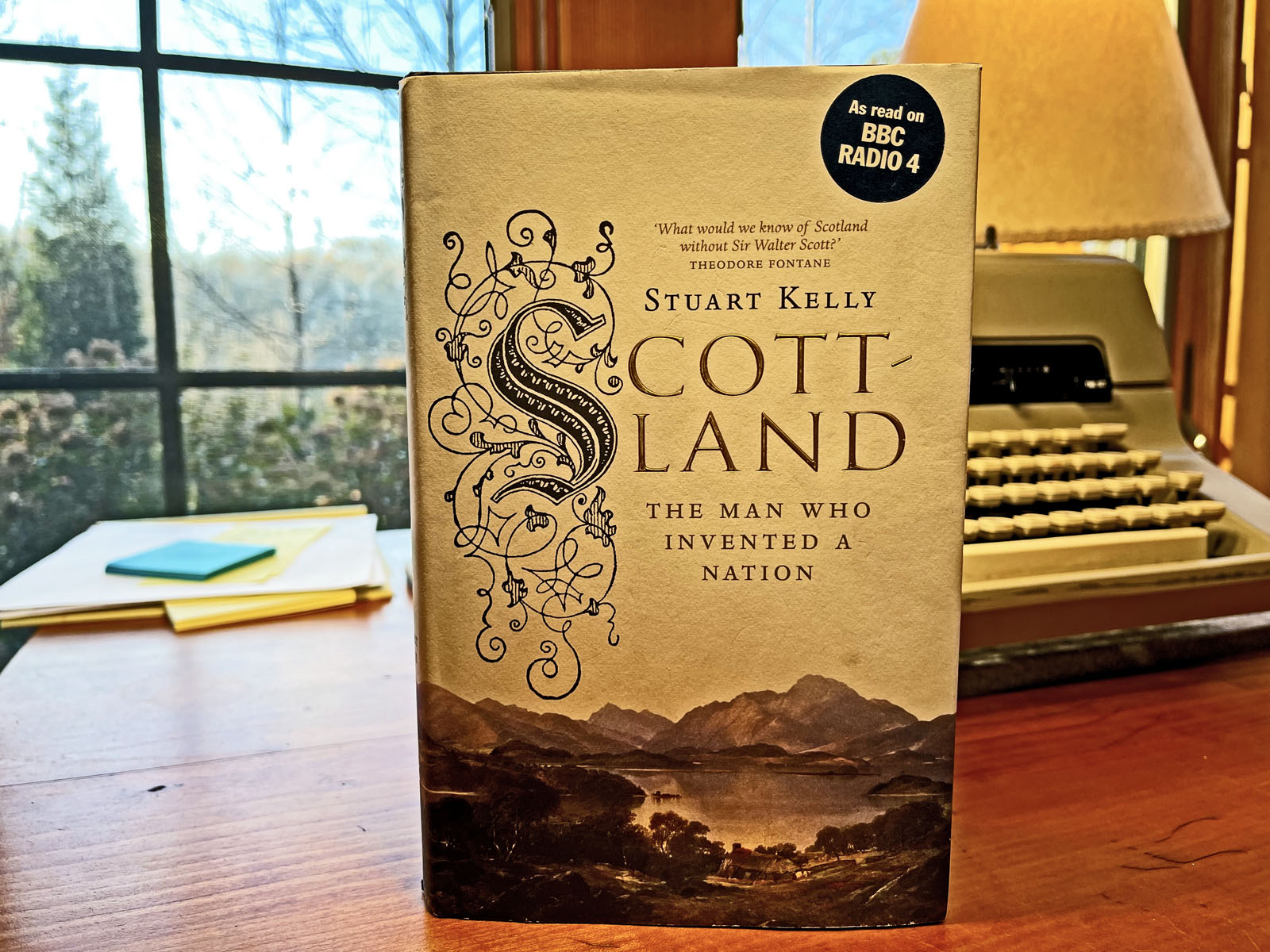

Scott-Land: The Man Who Invented a Nation. Stuart Kelly, Polygon (Edinburgh), 2010. 328 pages.

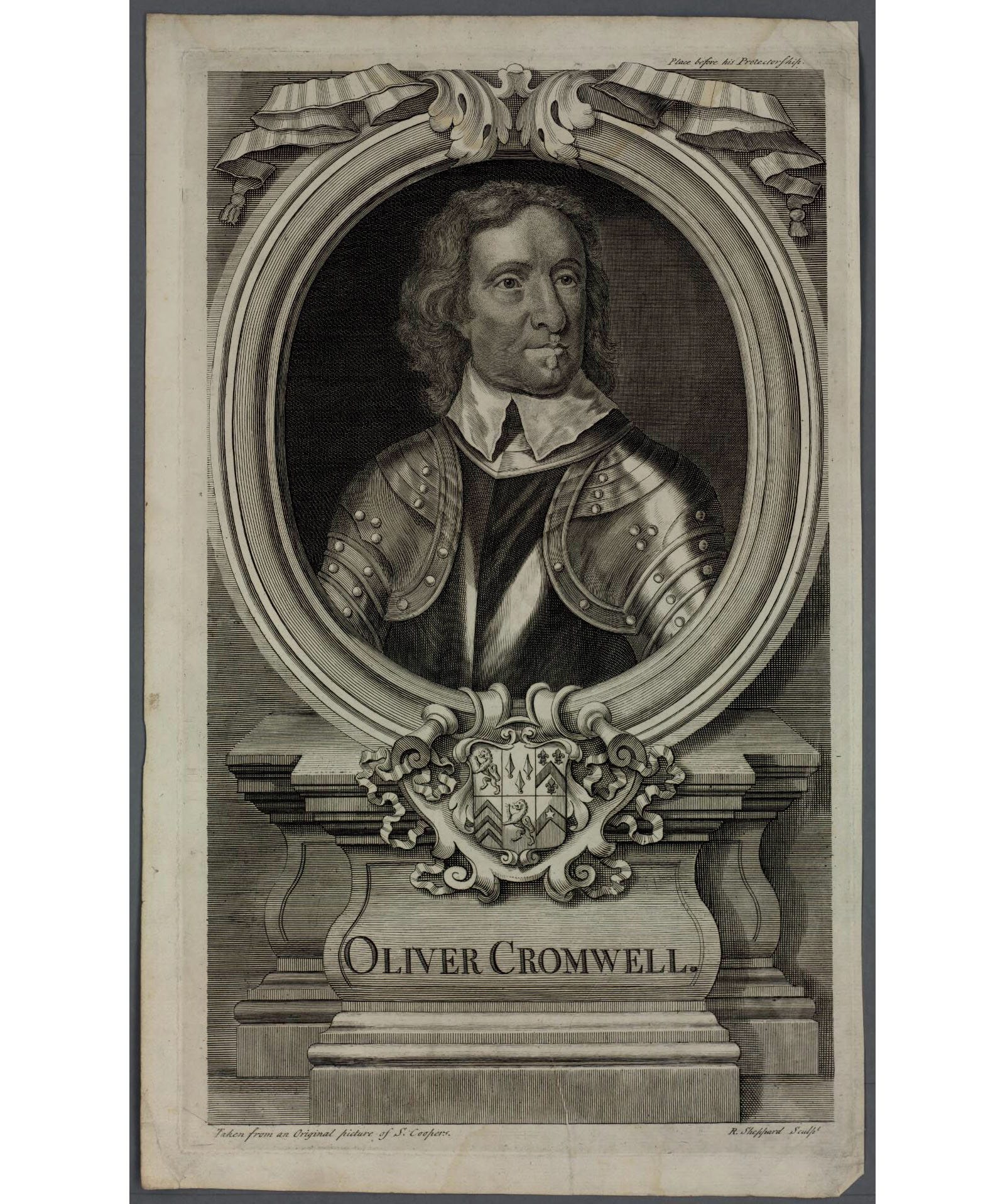

First, a disclaimer. I did not read the entire book. By the time I was halfway through, so much of the book seemed only obliquely relevant to the subject of Sir Walter Scott’s novels that I scanned the remainder of the book for the bits that seemed relevant and ignored the rest. Others, I grant, may see this book differently, if they’re interested in such matters as how Diana Gabaldon, Tony Blair, or Dr Who may relate to Walter Scott. I wasn’t particularly interested.

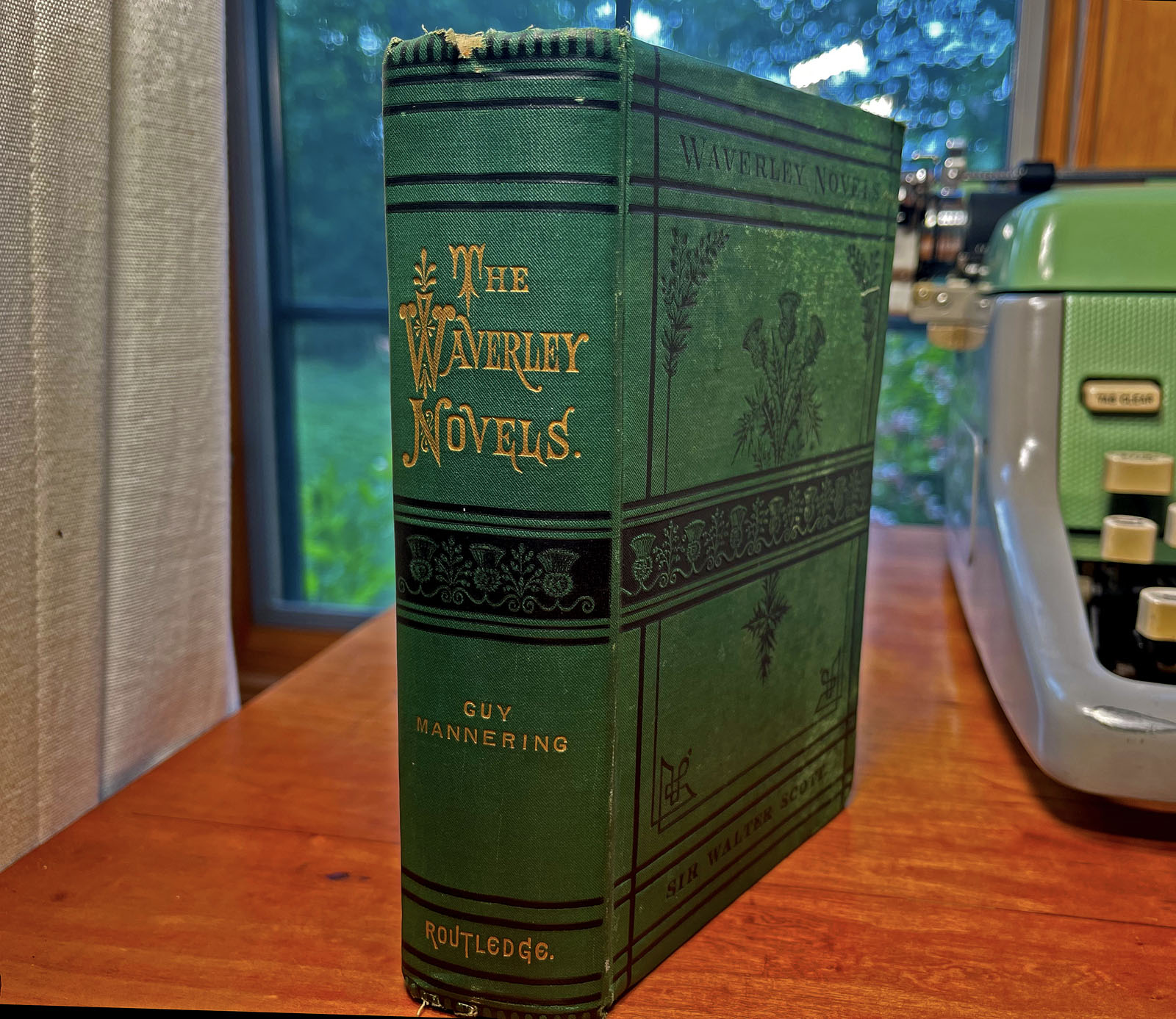

However, I greatly commend the author for writing a book about Walter Scott, given that Scott is hardly ever mentioned anymore, except maybe by travelers who emerge from Waverley Station in Edinburgh and see the enormous Scott memorial for the first time. The author, in fact, seems to assume that the readers of Scott-Land have not read any Scott, since few people read Scott anymore.

It’s an odd thing, isn’t it? Walter Scott as a cultural phenomenon is deemed to be worth writing books about. But few people are willing to go out on a limb and make the case that Scott is still worth reading and taking seriously, or that Scott’s books are still worth talking about the way we still talk about Jane Austen or George Eliot, or even Charles Dickens.

This is not an academic book. It’s meant to be entertaining. It’s often flippant and even snarky. Kelly seems to think that if he — or even we — took Walter Scott too seriously, that would be embarrassing, like liking the Pet Shop Boys. Kelly’s connection with Scott isn’t even particularly literary. Kelly grew up in the Borders area of Scotland near Scott’s baronial home at Abbotsford, so Kelly’s connection to Scott has a cultural rather than a literary origin, though Kelly studied English at Oxford. This is purely a guess on my part, but I’d guess that Kelly writes about Scott the same way that one would have to talk about Scott today at Oxford — with a knowing smile or even a touch of smirk.

But I’m probably an odd duck of a reader, because I have read Scott. I also take Scott seriously. A part of my personal view, though, is that we probably wouldn’t want to read Scott today because of an interest in the history of Scotland but rather because of an interest in the history of the English novel, with the bonus that in reading Scott we also get a great deal of the Scots language as well as English. A friend asked whether I’d agree that Scott’s themes are less relevant today than, say, Jane Austen’s or Charles Dickens’. I would agree. I’m certainly not arguing that Scott should be at the top of our reading list in 19th Century novels; only that he should be on it, for dedicated readers, anyway.

The first question one might ask if one is considering reading Scott is, “What should I read?” My suggestion would be — anything but Ivanhoe. Scott is at his best, I think, when he is writing not about his beloved kings and heroes but when he

is writing about ordinary people in ordinary places. I’d suggest The Heart of Mid-Lothian or The Antiquary as a good place to start.

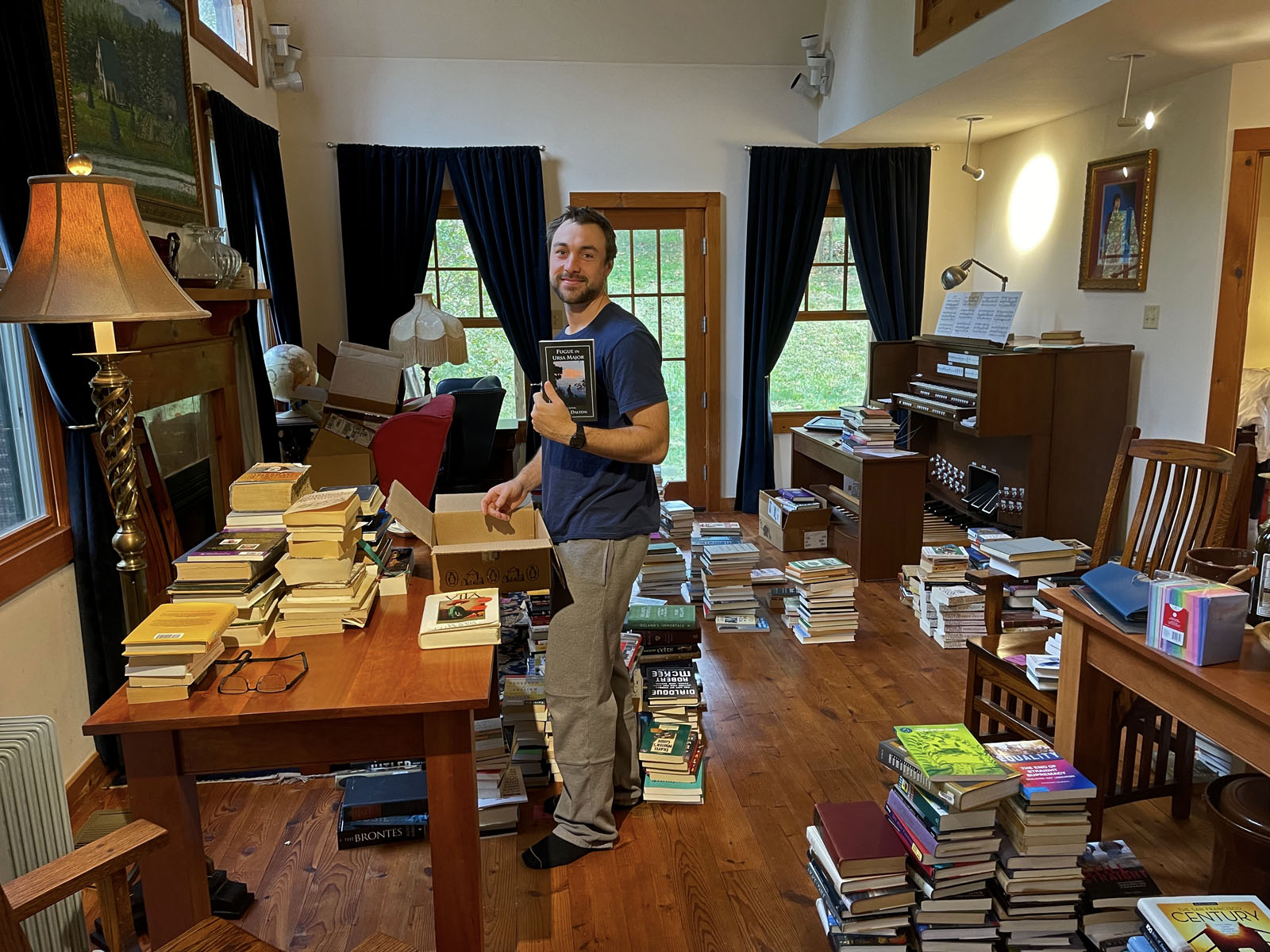

I’m still looking for a recent academic book about Sir Walter Scott. Meanwhile, I very much agree with what the academic says in the short video below, in which she answers a question after a lecture.