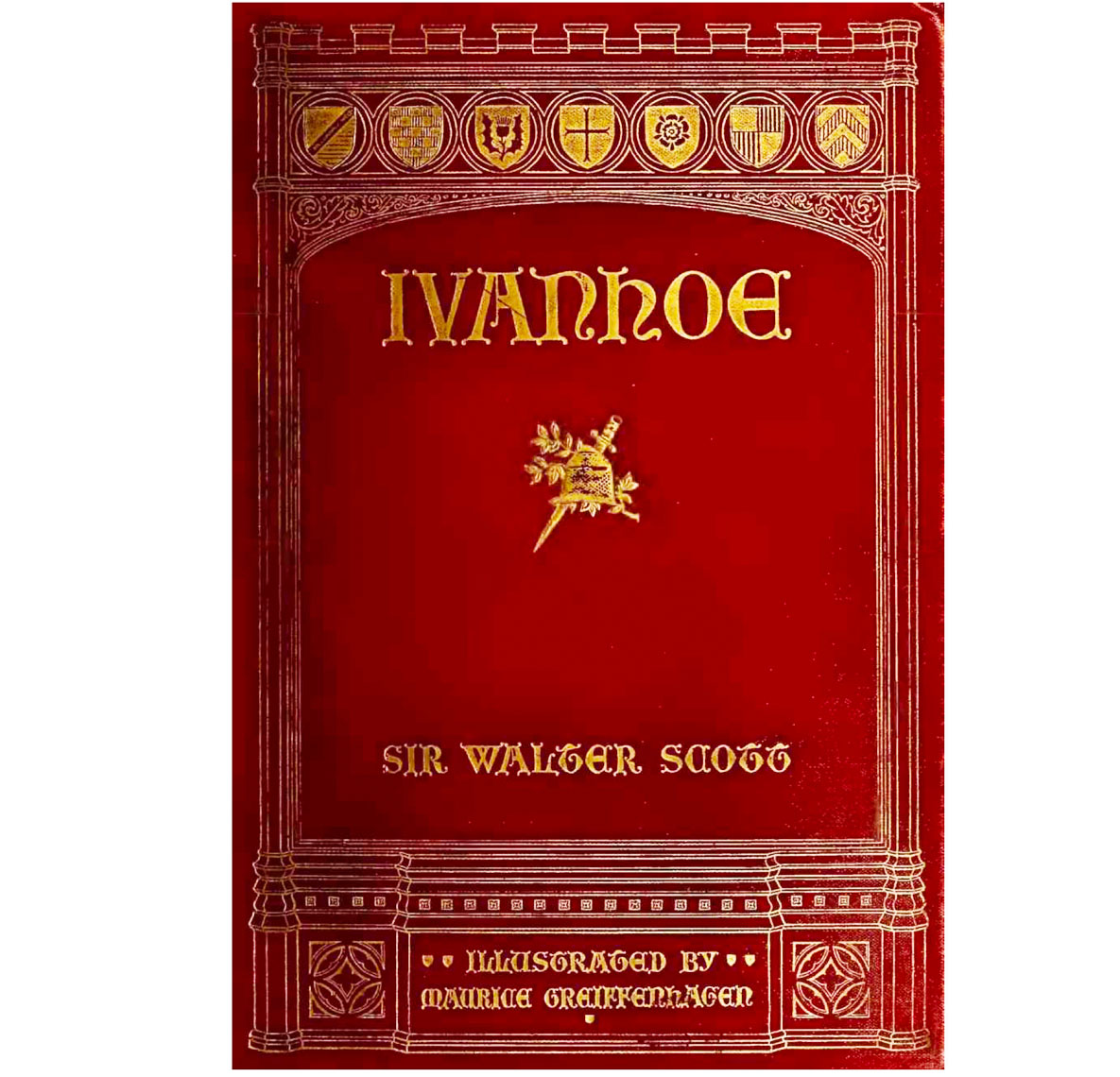

Once again, unable at present to find any newer fiction that seems worthwhile, I have turned to Sir Walter Scott — this time, Ivanhoe.

Reading Sir Walter Scott can be hard work for contemporary readers. Even in the early 1800s when his novels were being published, Scott’s style would have been pretty florid, I think. But somehow (if you’re stoic enough to read him) that remains part of the charm today. In Ivanhoe, at least, because it is set in England rather than in Scotland, readers won’t have to work their way through page after page of dialogue in the Scots dialect. But dialect or no, Scott is in many ways a linguist, very much aware of how he employs language and dialect for literary effect. And as a historian, Scott also would have been aware of the history of the English language itself and how the French and Anglo-Saxon languages mixed and merged into English in the miserable (unless you were Norman) years after the Norman Conquest.

Consider this conversation from the first chapter of Ivanhoe. Ivanhoe is set in 12th Century England. The conversation is between a Saxon swineheard (Gurth) and the court jester (Wamba) of a staunch Saxon noble:

“Why, how call you those grunting brutes running about on their four legs?” demanded Wamba.

“Swine, fool, swine,” said the herd, “every fool knows that.”

“And swine is good Saxon,” said the Jester; “but how call you the sow when she is flayed, and drawn, and quartered, and hung up by the heels, like a traitor?”

“Pork,” answered the swine-herd.

“I am very glad every fool knows that too,” said Wamba, “and pork, I think, is good Norman-French; and so when the brute lives, and is in the charge of a Saxon slave, she goes by her Saxon name; but becomes a Norman, and is called pork, when she is carried to the Castle-hall to feast among the nobles; what dost thou think of this, friend Gurth, ha?”

“It is but too true doctrine, friend Wamba, however it got into thy fool’s pate.”

“Nay, I can tell you more,” said Wamba, in the same tone; “there is old Alderman Ox continues to hold his Saxon epithet, while he is under the charge of serfs and bondsmen such as thou, but becomes Beef, a fiery French gallant, when he arrives before the worshipful jaws that are destined to consume him. Mynheer Calf, too, becomes Monsieur de Veau in the like manner; he is Saxon when he requires tendance, and takes a Norman name when he becomes matter of enjoyment.”

The words at play here, of course, are bœuf for what we English speakers call cows when we eat them, and porc for what we call pigs when we eat them. My guess is that Scott is suggesting a plausible linguistic history for how it came to be that we use separate words for creatures on the hoof versus creatures on the plate.

So clearly Scott is well aware, when he writes, of whether he is using English words of French or of Anglo-Saxon origin. But here’s the sad thing. One of the reasons why Scott can be so difficult to read, and for why the rhythms of his writing can be so choppy, is that he loves English words of French origin and uses them a lot. Here’s a sample of French words (little changed from their Latin roots, of course) gleaned from just a few pages of the first chapter of Ivanhoe: misapprehension, refractory, rivulet, dejection, construed, disposition, obstreperously, proprietors, importations.

I always use Tolkien as the best example of an English writer who wisely and consciously writes out of the Anglo-Saxon half of the English language. Can you imagine Tolkien using such words as obstreperously or refractory? Of course not.

It’s as though Scott knows that it is wrong and pretentious (oops … French!) of him to do this, but he does it anyway. Proving that he knows better, he writes (again from the first chapter of Ivanhoe):

In short, French was the language of honour, of chivalry, and even of justice, while the far more manly and expressive Anglo-Saxon was abandoned to the use of rustics and hinds, who knew no other.

There are other little jokes that relate to Scott’s awareness of languages. When he names a character Albert Malvoisin, for example, which is more or less French for “wicked neighbor,” you know that character is going to be a villain.

Please don’t misunderstand me, though. I love Walter Scott and enjoy reading him, Frenchified or not. But I’m going to test a theory as I continue to read Ivanhoe (I’ve just started). That is that Scott may primarily use French when he wants to be funny (he’s often hilarious), but that he sticks to Anglo-Saxon when he wants to be serious and to talk to another native speaker of English heart to heart — another thing that Scott does well, though those kinds of tender scenes, I think, tend to be near the end of his novels rather than at the beginning.

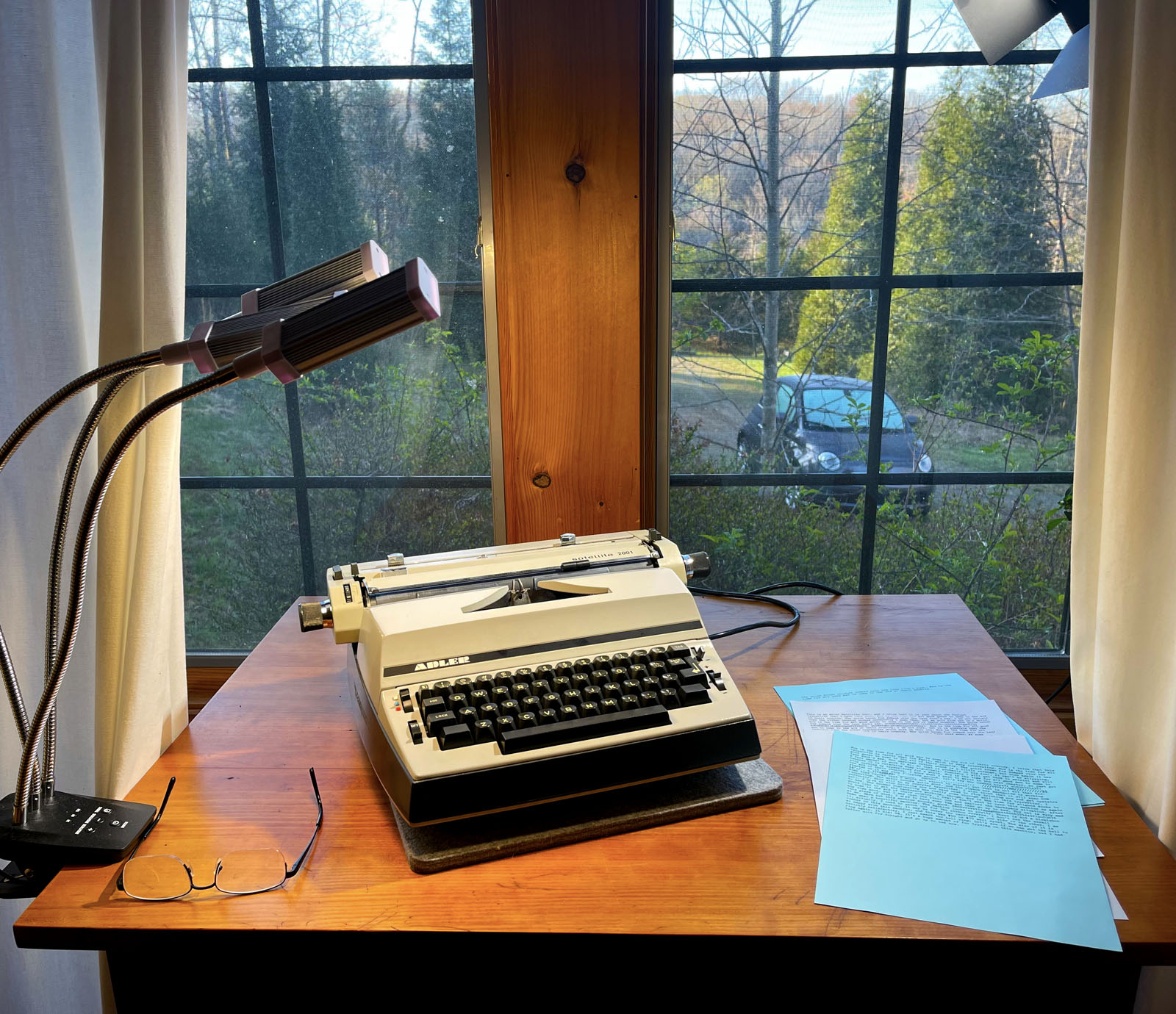

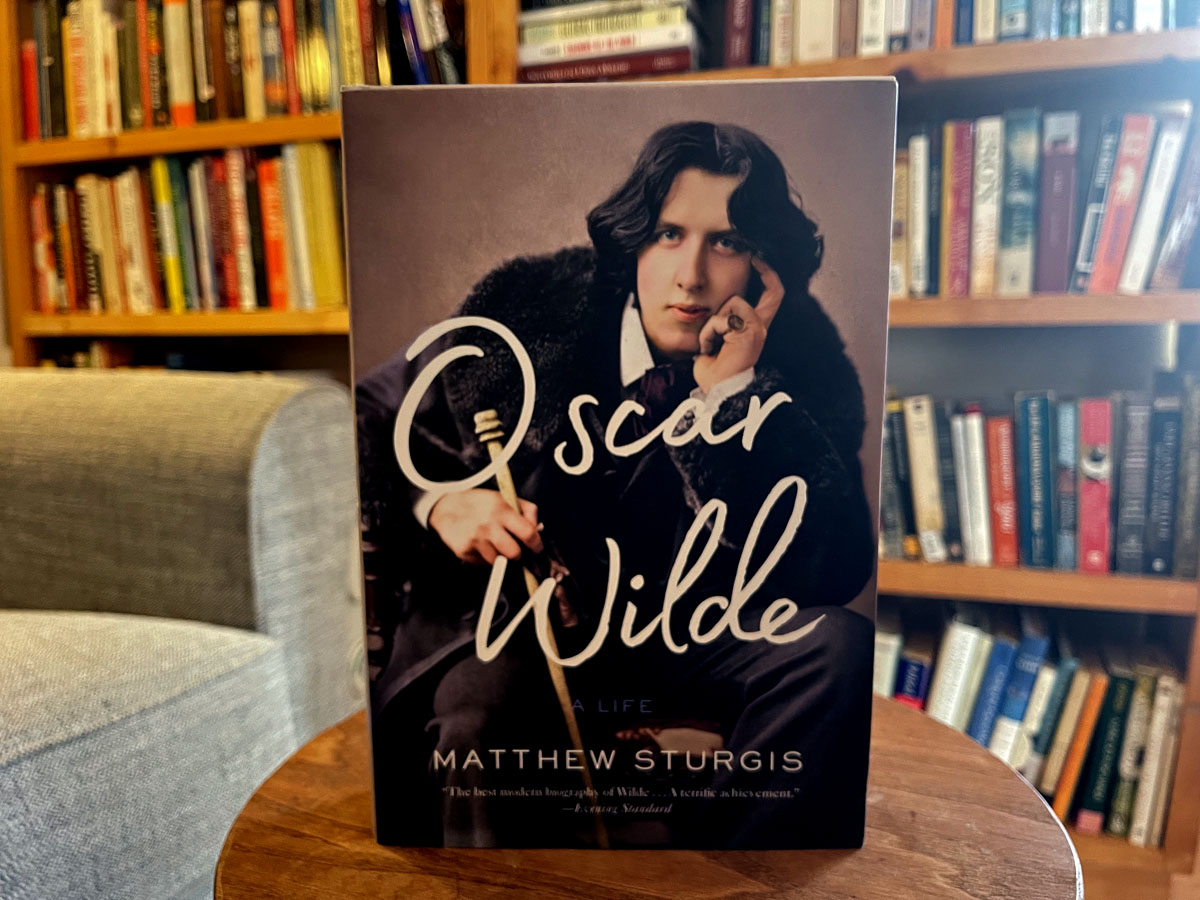

Yes. I’d encourage all lovers of English fiction to dust off their stoic-hats, take a deep breath, fortify their patience, and pick up a novel by Sir Walter Scott. At present I’m reading the Gutenberg.org edition on my Kindle, but I’ve also ordered an 1880 hardback edition from the U.K., which should be here in a couple of weeks. I’m having more shelves built for my little library room, so why not, since it’ll probably take me a month to read Ivanhoe. Antique fiction reads better somehow if you’re holding an antique book in your hands.