“The Porteous Mob,” James Drummond, 1855. The painting is on display in the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Click here for high-resolution version.

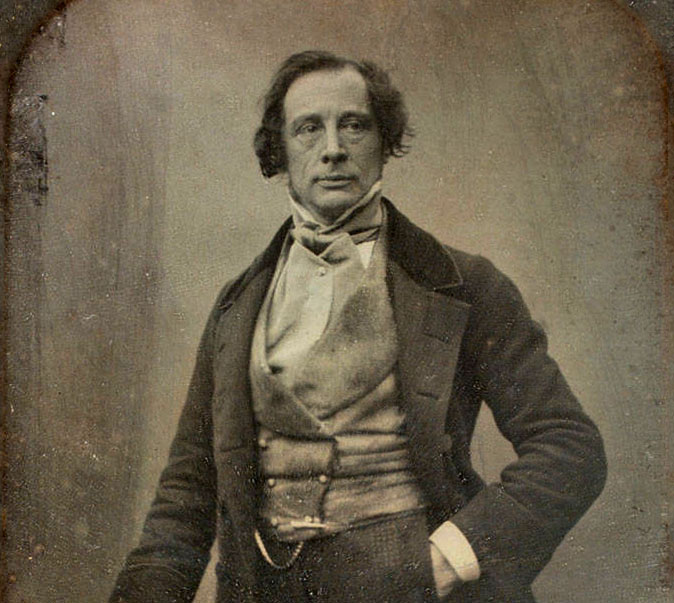

A couple of weeks ago, I came across an article in The Herald of Scotland in which a scholar of literature urged filmmakers to make “blockbuster” movies from Walter Scott novels. The article is “Call for Walter Scott’s novels to be given film treatment,” Aug. 10.

I found the article charming, but I also was skeptical. At that point, I had read only one Walter Scott novel, The Antiquary, 1816, the third of Scott’s Waverley novels. That novel was a good enough read, but it’s not blockbuster material. Had I continued to judge Scott’s novels based only on the The Antiquary, I would not have rated him all that high, and I would have continued to wonder whether the high esteem in which the Scottish hold Scott has more to do with nationalism than with literature.

But any scholar, in this age, who makes a specialty of 19th Century literature automatically has my respect. So, I thought it likely than Alison Lumsden, who is quoted in the article, must know things that I don’t know. I ordered a used copy of The Heart of Mid-Lothian from Amazon. It’s a 1947 edition, poorly printed and with small type, but I didn’t want to read this book on a Kindle. Almost always, when old books are made into Kindle editions, they are full of typos because the text was scanned and was poorly edited, or not edited at all, for scanner errors.

The novel was first published in 1818. That makes it more than 200 years old. I had just finished reading Charles Dickens’ Martin Chuzzlewit (1842) and Barnaby Rudge (1841). To read these novels back to back seemed like a good idea, not least because my neural circuits for parsing long 19th Century sentences were fully warmed up, and also because I was curious how the Dickens would compare with the Scott.

The Heart of Mid-Lothian is a seriously good novel, and I now agree with Alison Lumsden: It deserves to be made into a blockbuster.

One of the reasons Lumsden gives for bringing Scott to the screen is “because I think that’s a really good way of getting people to engage with writers again — they see the film and then they read the book.”

No doubt Professor Lumsden has students who would be able to read The Heart of Mid-Lothian. But my guess is that this novel would be insurmountable by most young readers today. The novel is long. The sentences are very long. For the first 120 pages, hardly anything happens. Most daunting, though, is that the dialogue (of which there is a great deal) is in dialect, written phonetically. (Some people would see this speech not as a dialect of English, but as a separate Scots language.) Thus there is a great deal of reader friction. Other readers may have other methods, but my method is to sound the dialogue in my mind. Usually it can be understood from the sound of it. If a character uses the word “waur” in a sentence, it’s not too difficult to recognize that “waur” means “worse.” The word “maun,” meaning “must,” will already be understood by readers of English literature. But some words simply have to be looked up, such as “gleg,” meaning sharp or wary. I learned the meaning of “Gardyloo!” from a walking tour in Edinburgh, in which I also learned about the Grassmarket and Half-Hanged Maggie, and where the gallows used to be. (If you love Edinburgh or are planning a trip there, that alone is a reason to read this novel.)

Even the people of Edinburgh speak in dialect. But characters from the Highlands are more challenging:

Hout, tout, ne’er fash your thumb, Mrs. Putler. The law is put twa-three years auld yet, and is ower young to hae come our length ; and pesides, how is the lads to climb the praes wi’ thae tamn’d breekens on them? It makes me sick to see them. Put ony how, I thought I kend Donacha’s haunts gey and weel, and I was at the place where he had rested yestreen ; for I saw the laves the limmers had lain on, and the ashes of them ; by the same token there was a pit greeshoch purning yet. I am thinking they got some word out o’ the island what was intended — I sought every glen and cleuch, as if I had been deer-stalking, but teil and wauff of his coat-tail could I see — Cot tam!

Note the beautiful rhythm of this little speech. Rhythm has a great deal to do with why we find Scottish accents so charming.

There is another factor that Chuzzlewit, Rudge, and Mid-Lothian have in common that may be offputting to contemporary readers. That is that the dramatic trajectories are very different. Contemporary readers will expect a story to begin with some dramatic action. Then the author will be forgiven for a bit of exposition. Then the action will resume and build step by step until the climax. The climax will be followed by a very short denouement. Readers of 200 years ago, no doubt, would have been entirely content with a different sort of trajectory. For many pages — maybe even 20 percent of the novel’s length — nothing much will happen. Some scenes will be set and characters will be introduced. But nothing happens, and how the characters and settings are related is not disclosed. There will be clues and a bit of foreshadowing, but there is hardly any dramatic tension. Finally the threads of the plot (and the subplots) will start to emerge. By the halfway point, the reader will finally see where the story is going. The climax will occur very early, around the three-quarters mark, followed by a very long denouement. Readers who anticipate this might be more motivated to stick with an antique novel if they have low expections that anything important will happen until well after 100 pages.

For that reason, books such as The Heart of Mid-Lothian would present some big problems for filmmakers. A filmmaker might, for example, have to start the movie with a high-drama event that doesn’t occur until much later in the story, and then depend on a flashback to introduce the characters and settings and to do the necessary exposition. Or screenwriters might cut the first quarter of the novel completely, and dribble in the background some other way. Exposition is another challenge. Contemporary writers avoid relying on exposition, in which the author explains what is happening. Instead, the action is expected to tell the story. In Mid-Lothian, the readers will encounter many pages of exposition, and only the key dramatic parts will be handled with scenes and dialogue. The art of storytelling and the expectations of readers have changed. But old stories are good stories all the same.

As the drama in Mid-Lothian picked up and peaked, I found myself staying up late to read. Was it a good read, worth the effort? Yes!

There are other rewards, though, for reading a novel like this. I understand much better now why the Scottish hold Scott in such high esteem. I have a much better feel for some Scottish history — particularly the events that followed “the Glorious revolution,” though that history is complicated and remains vague to me. Scott was a lawyer. He works in some very interesting facts about Scottish law, for which he clearly had great respect. And though I don’t think that Scott was particularly religious, a major theme in Mid-Lothian is the religious conflict in Scotland that was closely connected with conflict around the union of Scotland and England. One of the characters in Mid-Lothian, David Deans, goes into long and rather tedious disquisitions on doctrine. Scott refers to Deans as a “proser,” and it’s fairly clear that Scott was making fun of doctrinal hair-splitting, as well as of old men who talk too much.

As for the Porteous riots, the riots are not central to the plot of Mid-Lothian, but the riots have a great deal to do with the characters. The Porteous riots — of which Scott’s account is surely historically accurate — also ruffled feathers in London, and those ruffled feathers in London also connect with the plot.

Jeanie Deans, Mid-Lothian‘s heroine, will seem like a prude, I think, to young people today. But Jeanie’s sister, Effie, is very different. The difference between these two sisters will give modern young readers plenty to think about. And for students looking for a topic for a paper, I suggest this: Compare the hangman characters in Barnaby Rudge and The Heart of Mid-Lothian. Was Scott as much a social reformer as Dickens? How did the Scottish of the time justify capital punishment? Was the public attitude toward capital punishment starting to change? Why or why not? How does a duke’s attitude compare with that of a peasant, or with that of a religious character such as David Deans?

I should say a few words about the moral tone of The Heart of Mid-Lothian. It is an extended meditation on suffering and justice. Here is a quotation from Jeanie Deans:

O madam, if ever ye kend what it was to sorrow for and with a sinning and a suffering creature, whose mind is sae tossed that she can be neither ca’d fit to live or die, have some compassion on our misery! — Save an honest house from dishonour, and an unhappy girl, not eighteen years of age, from an early and dreadful death! Alas! it is not when we sleep soft and wake merrily ourselves that we think on other people’s sufferings. Our hearts are waxed light within us then, and we are for righting our ain wrangs and fighting our ain battles. But when the hour of trouble comes to the mind or to the body — and seldom may it visit your Leddyship — and when the hour of death comes, that comes to high and low — lang and late may it be yours! — Oh, my Leddy, then it isna what we hae dune for oursells, but what we hae dune for others, that we think on maist pleasantly. And the thoughts that ye hae intervened to spare the puir thing’s life will be sweeter in that hour, come when it may, than if a word of your mouth could hang the haill Porteous mob at the tail of ae tow.

In short, though I read this novel in two weeks, I feel as though I just finished an entire semester in a tough course on Scottish literature and history that I found very rewarding. Thank you, Professor Alison Lumsden of the University of Aberdeen.

The Scott Monument in Edinburgh’s Princes Street Gardens. The monument stands on prime real estate just west of Waverley Station, below, and northeast of, the castle. I’ve never been inside this tower and have only admired it from the park, from which I took this photo, but I’ll climb the steps on my next trip. The tower is over 200 feet high.

On a lighter note: It’s entirely possible that the difficulty of understanding the many Scottish accents has been a running joke among speakers of English for centuries. I’d have to say that, as a native speaker of Southern Appalachian English, I am pretty good at parsing Scottish. I easily understand all of the video below. Twice in my life I have encountered English accents that I have not been able to understand, and it’s possible that one of them was speaking Gaelic rather than English. One was a Cockney taxi driver in London. I knew he was speaking Cockney only because of “My Fair Lady” (though I also read “Pygmalion” in high school and thought that it was one of the funniest things I’d ever read). The other was an old man, a beggar, I think, who approached me on the street in Edinburgh. Sometimes locals will take the time to school you, as with a clerk in the ferry office in the east of England who wouldn’t give me my ticket to the Hook of Holland until I correctly pronounced “Harwich” (which sounds like “Harridge” to me). There are very funny videos about this on YouTube with James McAvoy.