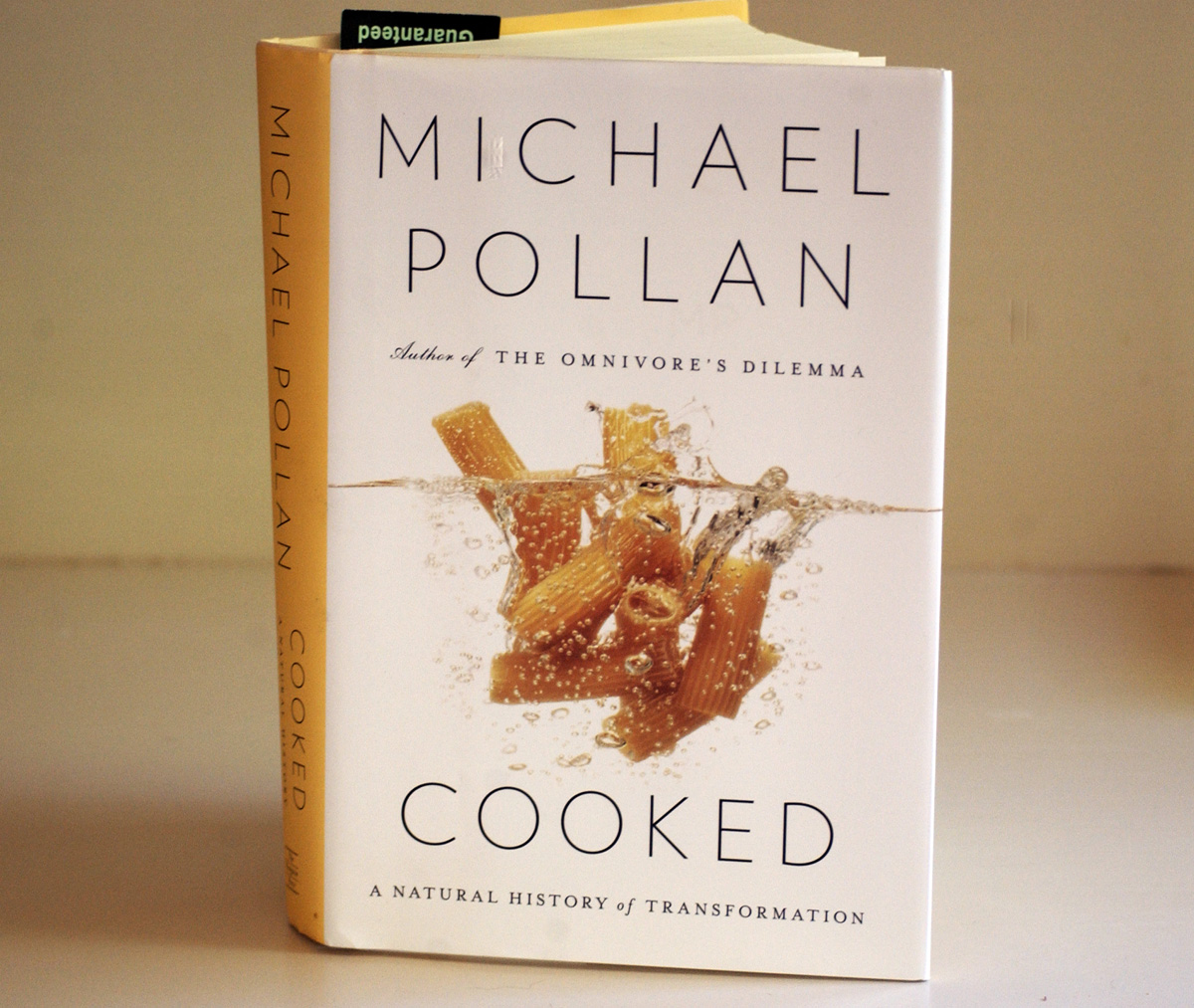

First test: not too shabby, especially for 75% whole wheat

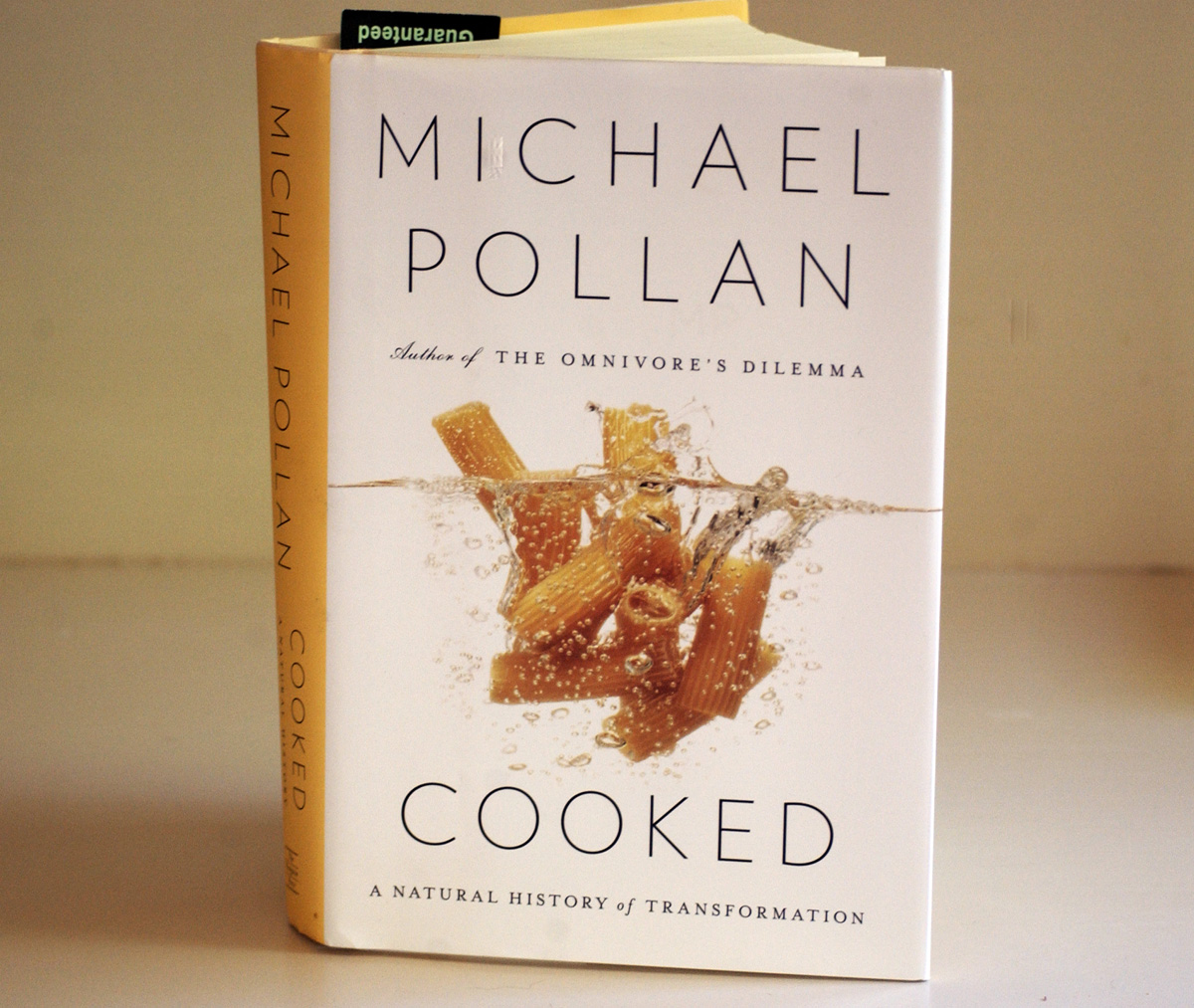

A week ago, I would have said that no hope existed that I would ever be able to make bread that could begin to compare with the bread one can buy from the excellent bakers of sourdough bread in the San Francisco Bay Area. Now I think it is possible. Michael Pollan’s new book, Cooked, has shown the way.

Part of my problem is that recipes are useless. No recipe can tell you, or teach how, how to make proper bread. Measuring (for example) has nothing to do with it. Rather, the ability to bake good bread can arise only from a deep understanding of how the process works. Pollan’s book has helped me figure out what knowledge I was missing that was holding me back. Don’t get me wrong — I can make delicious breads. But I had no idea how to get to the next level.

Pollan’s main source on bread for this book was Chad Robertson, who runs a bakery in San Francisco and who has a book out named Tartine Bread. When Pollan revealed that Robertson’s instructions for sourdough bread are more than 40 pages long but never quite gives a recipe, I knew that I had finally found my way to the next level. Those 40 pages are about the concepts behind the bread — exactly what I needed.

Here is a summary of some of the new knowledge I’ve gained that has helped fill some of my blind spots and misconceptions:

1. Sourdough is superior to yeast for many reasons. Sourdough bread is actually fermented, and some components of the flour are partially digested, releasing more nutrients and lowering the glycemic index of the bread. The lactic acid generated during the fermentation helps to strengthen the gluten. And gluten, of course, is what makes bread rise. I’ve started a new sourdough culture, which should be ready to use in about a week. My previous sourdough culture died out more than a year ago from neglect.

2. The reasons that whole wheat makes heavier bread can be explained, and there are ways of dealing with it. For one, the bran is sharp, and it cuts and weakens the strands of gluten. Overnight soaking of the flour softens the bran and helps reduce this sharpness. The shaping of the loaf is critical. Steam during the first part of baking is critical.

3. Random kneading of dough is useless. I have come to understand that the point is not just to form the gluten into strands, but to align those strands in such a way that they define the way you want the loaf to go when it rises. That is, the gluten strands form a kind of skeleton for the loaf. The point is to manipulate the dough in such a way that the gluten strands are formed into a skeleton.

4. The main reason steam is critical is that the formation of the crust must be postponed. If the crust forms too soon, it prevents the bread from rising. Throwing water into the oven is one way of dealing with this. But a better way is to bake in a covered Dutch oven. You remove the lid when the bread is about half done, after the loaf has already finished its “oven spring” — the inflation of the loaf when the heat hits it.

5. Maximizing oven spring is critical. The Dutch oven method works nicely. But another factor that is important to good oven spring is building up a proper gluten skeleton by manipulating the dough and to start baking at the right time. Bake too soon and there isn’t enough air in the loaf. Wait too long and the gluten becomes tired. Good oven spring is probably the single most important indicator of good bread and a good baker.

6. The dough must be wet. This probably has been my biggest failing as a baker over the years. Wet dough is difficult to work with. But it must be done.

It will be at least a week before I can attempt my first sourdough loaf. But I did make a loaf of bread with yeast this morning to practice manipulating the dough into a proper boule and to test the Dutch oven method. The loaf was 75 percent whole wheat and 25 percent unbleached white flour. It worked beautifully, and I got excellent “oven spring.” The top of the loaf broke open even though I forgot to slash it with a razor blade before baking.

Michael Pollan’s Cooked is not just about baking. He divides all cookery into four categories — fire (roasting, of meat in particular), water (cooking in pots), air (bread), and earth (fermentation). For each category, he seeks out experts and gets them to reveal their secrets. Though I have some experience with making sauerkraut, Cooked has motivated me to expand my food fermentation skills. And though the abbey’s kitchen is far from a slouchy kitchen, it’s exciting to have new, and higher, goals to aim for.