Ken, whom I regard as among the brightest and best-informed of his generation, has a concise and thoughtful post this morning in which he ponders the next steps in the evolution of his political views. I think I can guess what he was thinking about as he took the train back to Boston from Concord and a pilgrimage to Walden Pond. I considered adding a comment on his blog, but what I wanted to say is a little long for that. So…

1. Obama: I doubt that Obama and his machine understand the damage they have done and the price they will pay. They convinced millions of people, including young people, that if they worked to get Obama elected, things would change. But nothing changed. Obama governed just like a Republican. He tossed out a few rhetorical scraps from time to time to try to keep the wool over the eyes of those who had worked to elect him. But he also insulted us and boasted to right-wingers and corporatists about how he had betrayed his own base. Is the man so stupid that he thought he’d pay no price for that?

An analysis by the Nieman Foundation released on Oct. 3, when Occupy Wall Street was just beginning, seemed to conclude that the reason there had been no real protest from progressives was because, with the election of Obama, progressives thought that the mission had been accomplished. It took a while for the truth to sink in.

There are two important angles on that truth. The first and most obvious angle is that progressives were betrayed by Obama, that he used us to get elected, and then, to use Ken’s metaphor, cuckolded us. The second truth, and something about which I’m not sure Ken would agree with me since he speaks favorably of a third party, is that Obama’s election and subsequent betrayal shows that the 99 percent cannot just vote themselves out of this. It’s very important, I think, to acknowledge that truth and to do our best to understand why it is true. This truth, I believe, is so important that I am going to repeat it, in bold: We cannot vote our way out of this.

2. Voting won’t work. Reason 1: Once an elite succeeds in owning, corrupting, and controlling all the branches of the American system of democracy, it becomes almost impossible to “work within the system” to take the system back. That’s the whole point, of course, in owning, corrupting, and controlling the system. Votes no longer matter — only money matters. Once Congress becomes a pay-to-play system of hogs at the trough, only hogs at the trough can get elected. You don’t believe me? Try running for Congress and see how far you get. The courts not only back this up, the Supreme Court is actively looking for more precedents that it can use to strengthen the importance of money and weaken the importance of votes. Likewise, the White House is staffed by corporatists, many of them from Goldman Sachs. They don’t let people run for president unless they’re pre-approved by the establishment. Obama proved that.

3. Voting won’t work. Reason 2: The American people are lost in a sea of propaganda. The propaganda comes in two flavors: Right-wing propaganda, of the type produced by right-wing “think tanks” and dispensed by Fox News and Republican politicians; and establishment propaganda, which is pretty much everybody else. You only have to examine how the media fully cooperated with Bush/Cheney’s selling of the Iraq war to see how the mainstream media — corporate owned, of course — serves power, not truth. This is not going to change. In fact, it’s getting worse.

4. Voting won’t work. Reason 3: Though it might be possible with decades of work to build a third party that could win a national election against one of the two established parties, I think this is extremely unlikely. As a practical matter, all third parties do is split the vote and throw elections in the opposite of the intended direction. A third-party strategy not only won’t work, it would be absurdly counterproductive. And what’s to stop a third party from being co-opted by the establishment? A third party would be just as vulnerable to corruption in our pay-to-play system as the two established parties are.

Let’s do out best to crunch some numbers. About 25 percent of the American electorate are diagnosable right-wing authoritarians of the submissive type. (Please refer to the work of Bob Altemeyer for documentation of this replicable and replicated research.) They will believe whatever they are told and will vote however they are told. It’s this 25 percent that that ridiculous circus of Republican presidential candidates are playing to. The submissive right-wing authoritarians are ALWAYS going to align their votes with right-wing propaganda. Theirs are the cheapest, easiest votes to buy. Then, next we have the so-called “independents.” They make up another 20 to 25 percent of the electorate. Politicians speak of independents as though independents are some kind of elite voters above the “partisan” fray. But actually we know from statistical studies that “independents” are the most ignorant of the electorate, the least involved. They vote according to their whims. They’re the ones who are swayed by those dumb-as-rocks political ads that are all over television in the last days before an election.

So, around 50 percent of the American population are permanently blind and hopelessly stupid. They are so stupid, in fact, that elections prove over and over that they don’t even understand their own economic interests and that they’re totally capable of, even eager to, vote to increase their own poverty and marginalization. These are the 50 percent of the American people who sell their votes — cheap! — to the 1 percent.

That leaves about 50 percent of the American electorate who are capable of rational thinking. I say “capable” of rational thinking. But they also have moods. They can get caught up in backlashes. Sometimes they vote — or don’t vote — out of frustration. It was partly their frustration actually, and a backlash against Bush, that helped to get Obama elected in 2008. Who knows what kind of mood they’ll be in for the next election. And where the re-election of Obama is concerned, why does it matter much how rational people vote since Obama has governed for the 1 percent?

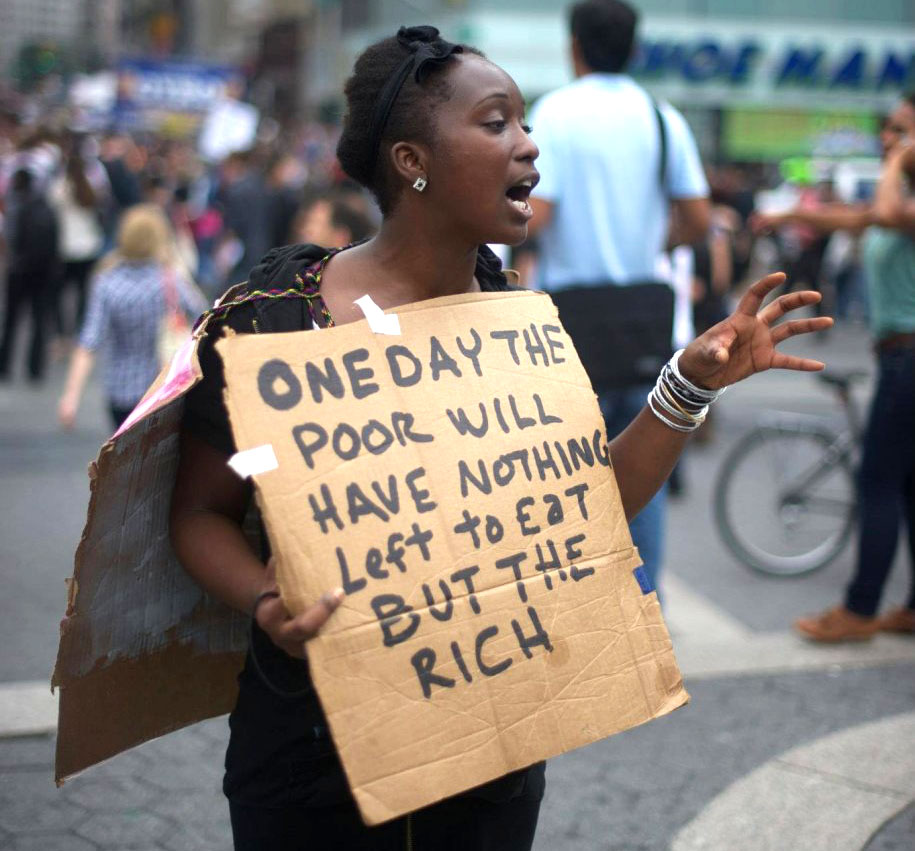

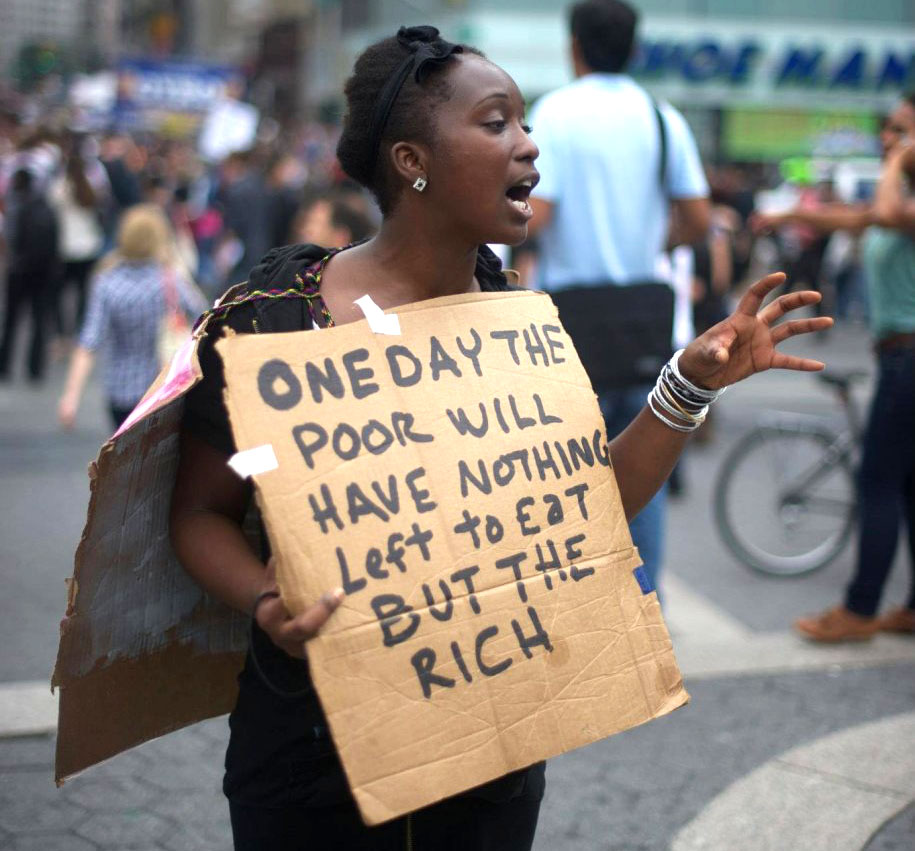

5. The Overton Window. Probably the biggest accomplishment of the Occupy Wall Street movement is that it has moved the Overton Window. The right-wing propaganda machine, with the co-operation of the establishment media, have moved the Overton Window so far to the right that Barack Obama, who has governed from the center-right, is called a “socialist” by the radicals to the right of him. The OWS movement has forced the establishment media to acknowledge that there are lots of progressive Americans — up to 50 percent, in fact — who have simply been pushed out of the conversation. Isn’t it amazing, really, that it took thousands of people in the streets to get the media to acknowledge that there are people in this country who want to talk about jobs and justice? But there is still a long way to go, because the Overton Window is still so far to the right that we can’t have a national conversation about global warming and the environment. And time is running out on that.

6. How the right wing won. They won because they’ve made a long-term project of it. They won because, for more than 30 years, they’ve been building a right-wing “think tank” and propaganda machine that can control right-wing and “independent” voters. The control of right-wing voters is done largely through alliances with the fundamentalist churches (they now call themselves “evangelical” — same thing). The conversion of the mainstream media from a truth-telling to a power-serving institution has served their cause. They have, through decades of brilliant work, transformed the system so that dollars, not votes, are the fundamental unit of government.

How can this situation be reversed? You’d think that it would not be difficult for approximately 50 percent of the American people to take the country back from a coalition of super-rich (1 percent), super right-wing authoritarians (25 percent), and super-stupid “independents” (24 percent). But it will be very difficult, because they are entrenched and can use all the power of government to preserve their power — up to and including those nifty new militarized, centrally coordinated local police forces that they were so eager to show off to us while they were breaking up OWS protests. And the rational 50 percent are not united and not in agreement about how to proceed.

I think the options fall into three categories.

Category 1: Revolution. Forget it. They have enough police power to put down a revolution while simultaneously fighting nine useless foreign wars. Until, at least, we all go bankrupt.

Category 2: Massive, unrelenting, non-violent civil disobedience. This could work, but it’s incredibly risky. Once confrontation begins, neither side, really, is truly in control of the outcome. Not to mention that they will be violent, even if the protesters are not. And yes they do, and will, use agents provocateurs.

Category 3: Long-term strategies involving education, organization, counter-propaganda, and coordinated economic pressure through boycotts, etc. Since the role of consumer is one of the two roles left to us, well coordinated consumer boycotts could be very effective. The other role left to us, of course, is taxpayer. But laws force us to pay taxes, while consumption is still mostly a choice. Pick a vulnerable company and take it down. Then another, and then another, until they get the message. There’s an important thing to keep in mind here: Our choices as consumers are far more powerful than our votes.

But there’s also a problem with category 3. Can we spend 30 years convincing the country that something must be done about global warming? Can we tell poor children who don’t have enough food at home and who have no hope for an education to wait 30 years? Are we going to let the 1 percent laugh all the way to the bank while we pay the taxes for another 30 years? Are we going to let our infrastructure fall apart for another 30 years? Let them scrape the top off mountains in West Virginia, or frack our water tables, for 30 more years? Impoverish students and crush them with debt for 30 more years? Offshore our factories for 30 more years and base our economy on banks and bubbles for 30 more years? Another 30 years in which the rich can ignore the law while the prisons are overflowing with poor people?

I’m just thinking aloud. But that, I think, is what the supporters of Occupy Wall Street need to spend the winter doing.