—————————————–

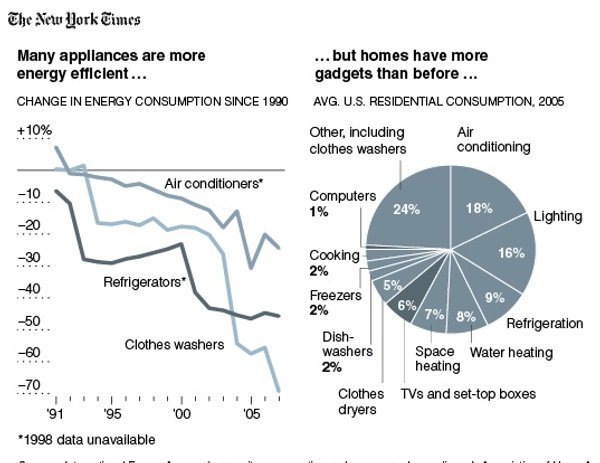

One of the nice things about new construction is that, largely because of tighter and smarter regulations, new homes and new appliances are more efficient and more frugal. My windows, with a U-factor of .31, are pretty darn snug, though no window is as efficient as a well-insulated wall. Local builders complain that Stokes County’s requirement for ceiling insulation is R-38, the same as in much of Canada, even though surrounding counties require only R-30. My Trane heat pump is far more efficient than heat pumps from the 1980s. Refrigerators have gotten much more efficient. Even my big iMac consumes far less energy than the computer it replaced.

For the month of July, with my cooling system running as needed all day and all night all month with thermostats set to 77 or 78, I used 604 kilowatt hours at a cost of $71.80. For September, with no heating and cooling needed, I’m expecting an electric bill of $35 to $40. My house is not a MacMansion. It’s 1250 square feet. [My electric company, Energy United, which is a rural electric cooperative, charges .0802 cents per kilowatt hour during the summer, meaning that my per-kilowatt charges were $48.44 for July. The rest of the bill is from taxes, fees, and fixed monthly charges.]

It has been fascinating to watch my new LG front-loading washing machine, which is Energy Star compliant. It’s astonishing how little water it uses. It’s very quiet. It spins at a very high speed to reduce dryer costs. Its behavior is very complex, controlled by a computer. Older washers with mechanical controllers were much more limited in how their wash cycles were set up.

The New York Times has a piece today on the patterns of energy consumption in the home and how they are changing.