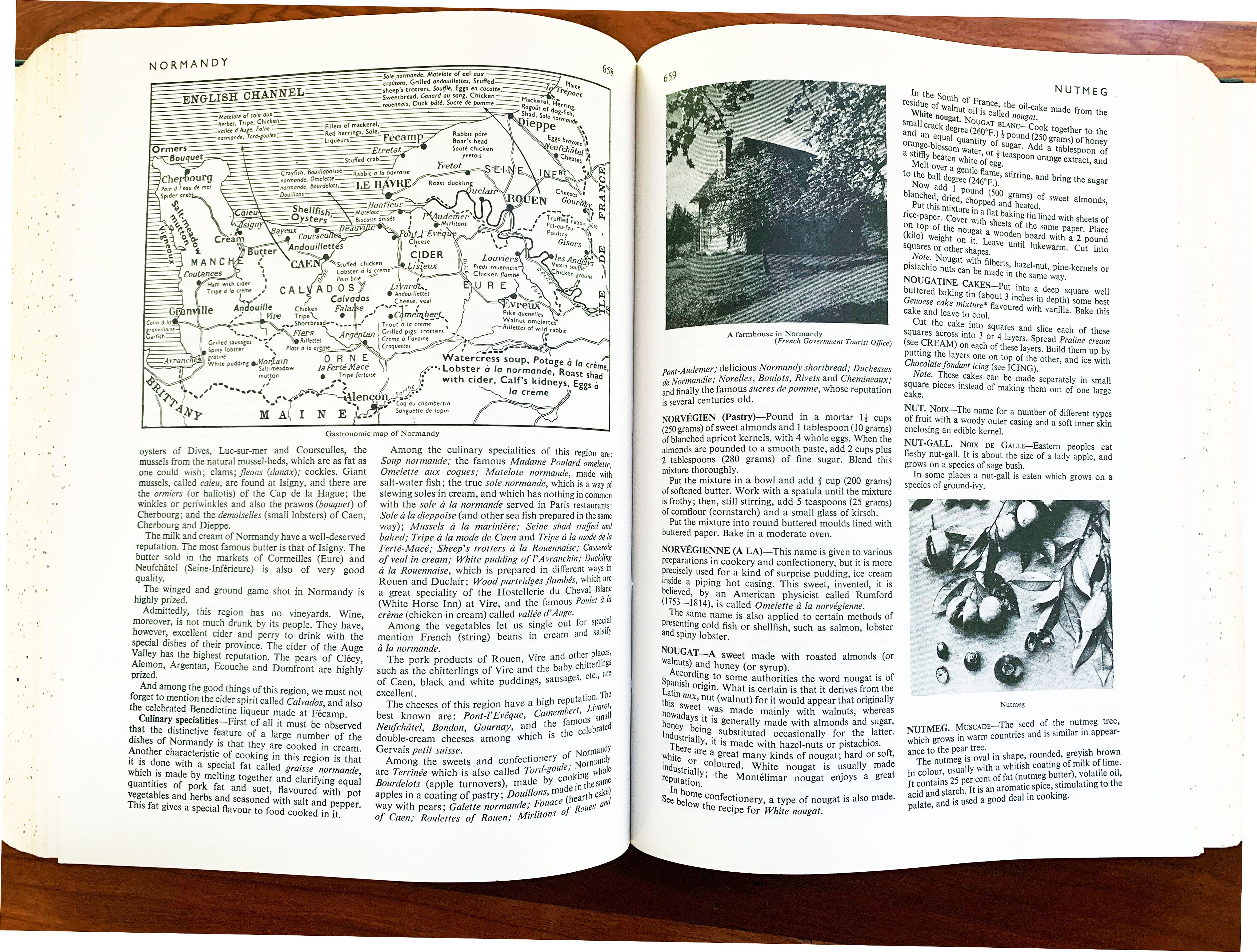

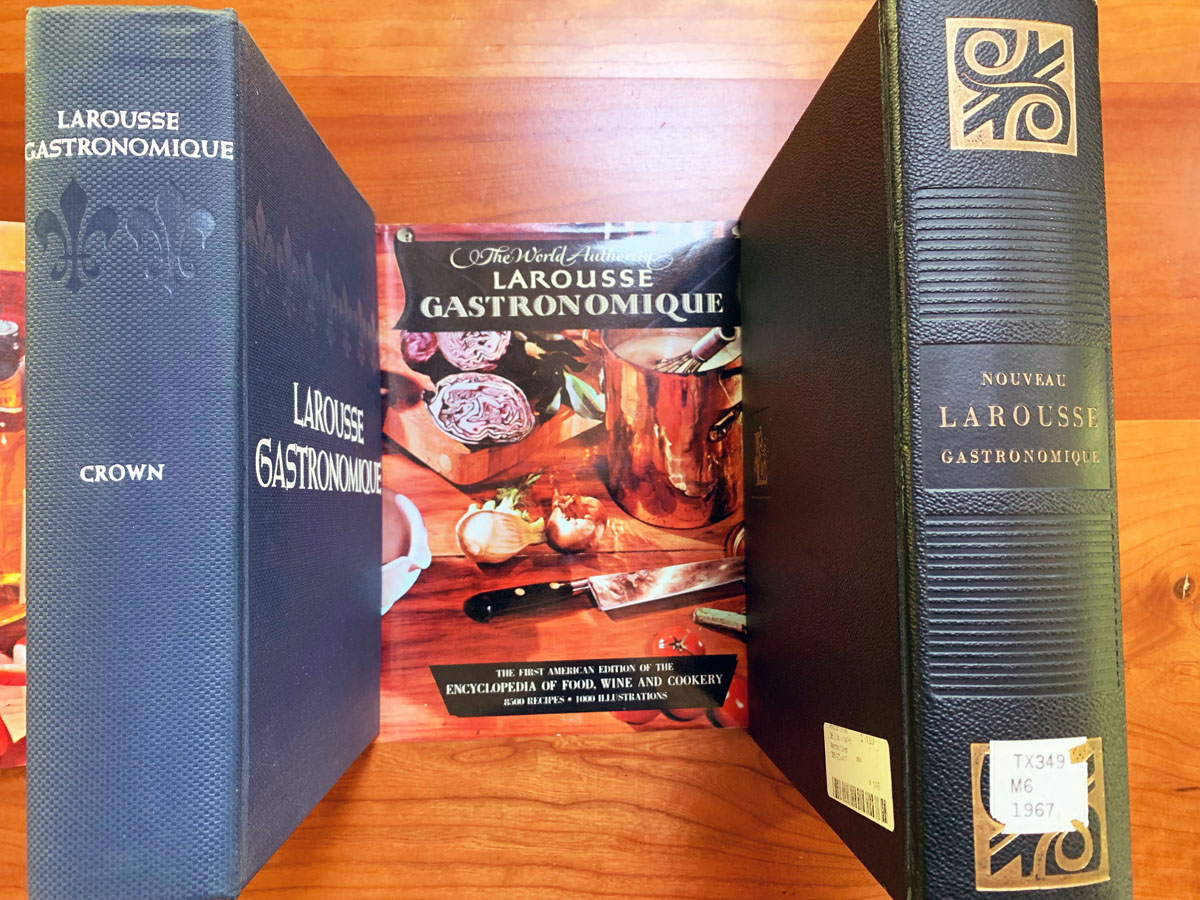

The 1960 French edition of the Larousse Gastronomique. Click here for high resolution version.

When you are browsing in an old bookstore, what catches your eye? For everyone it’s different, I’m sure. But one factor, probably, is the same: Whatever our tastes, we’re all looking for books that get better with age.

You’ll be dealing with thousands of books, so you have to move fast. When something catches your eye, you take it off the shelf for a closer look.

The books that I stop and examine are well-bound hardbacks that appear to be 60 to 75 years old, though anything published after 1920 is a candidate. Books that are older than that tend to be a little too antique and archaic. If I’m lucky, I find a book that is timeless, and I buy it.

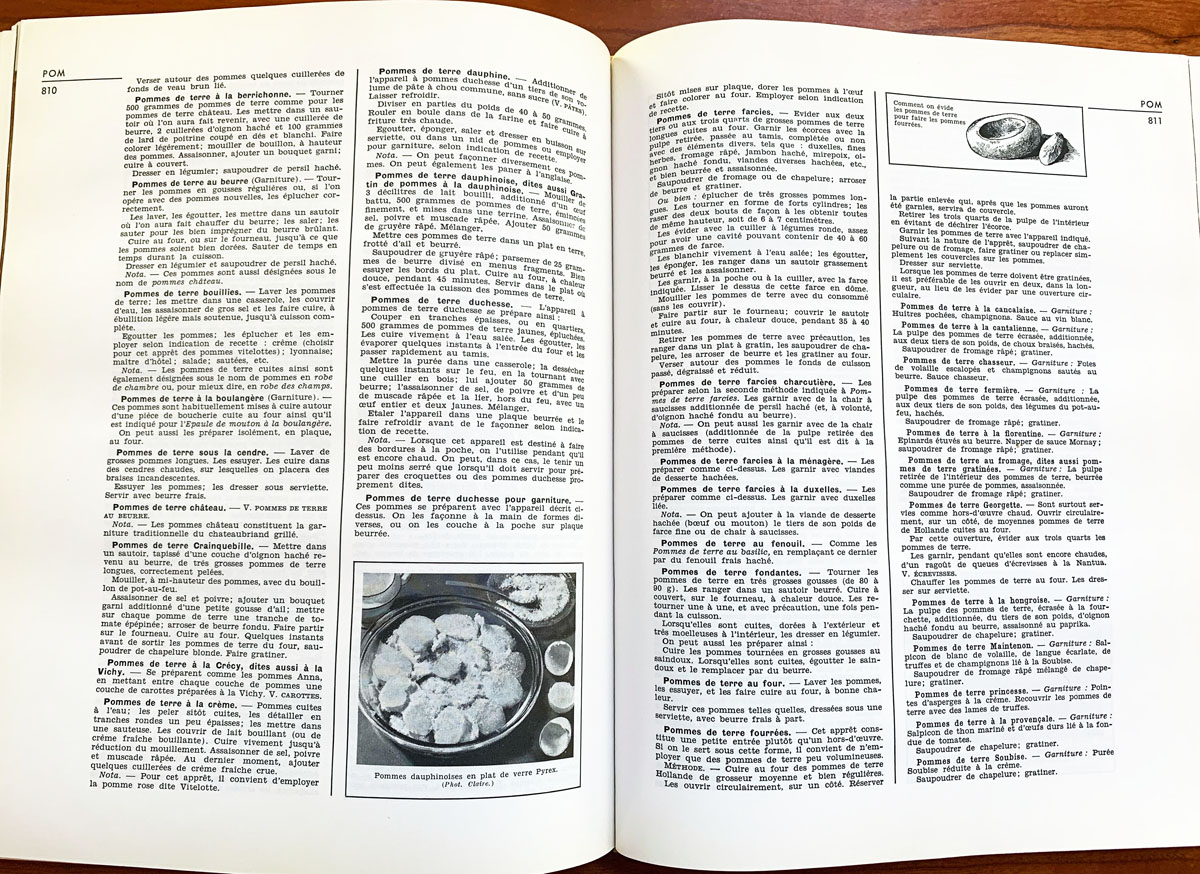

Last week I came across a copy of the 1960 French edition of the Larousse Gastronomique. The price was $10. It turns out that I already had — but had forgotten — a copy of the 1961 English edition. Though the English edition is just as thick — over 1,000 pages — the English edition is not complete. The English edition uses larger type and has been dumbed down a bit for Americans. The first edition of the Larousse Gastronomique was published in 1938. If you can find a copy of the first edition, you’ll pay hundreds of dollars for it. The newest edition, I believe, was published in 2001. I have no idea how the 2001 edition is different from the 1960 edition. But I prefer the timelessness of the 1960 edition.

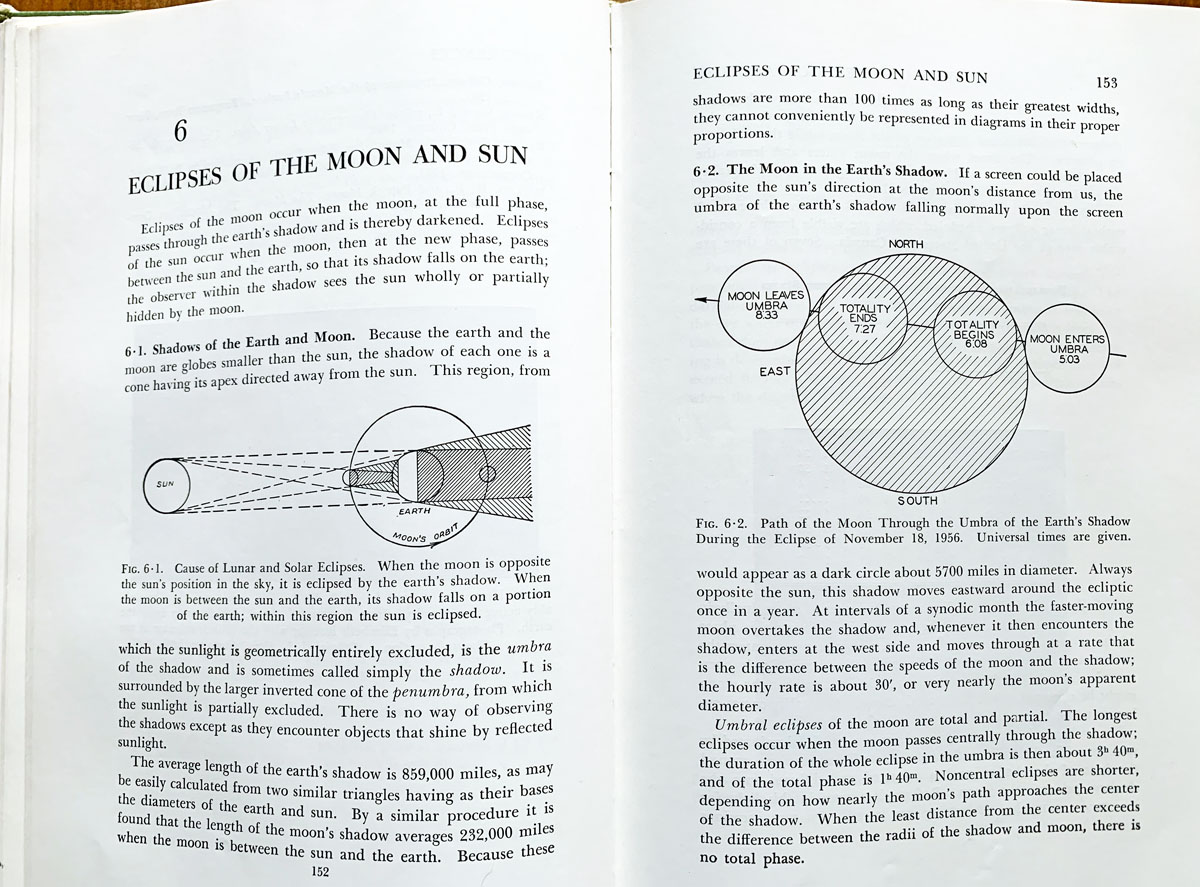

One of my favorite books cost me $1. It was in a box on the bookstore floor, deemed too low-value to even shelve. But what a find that was. It’s the eighth edition of Astronomy, published in 1964. This book had been a standard college textbook since 1930. Obviously there has been much progress in astronomy since 1964. Still, most of what was known in 1964 was accurate and still holds. This book is always on my nightstand for reading in bits and pieces.

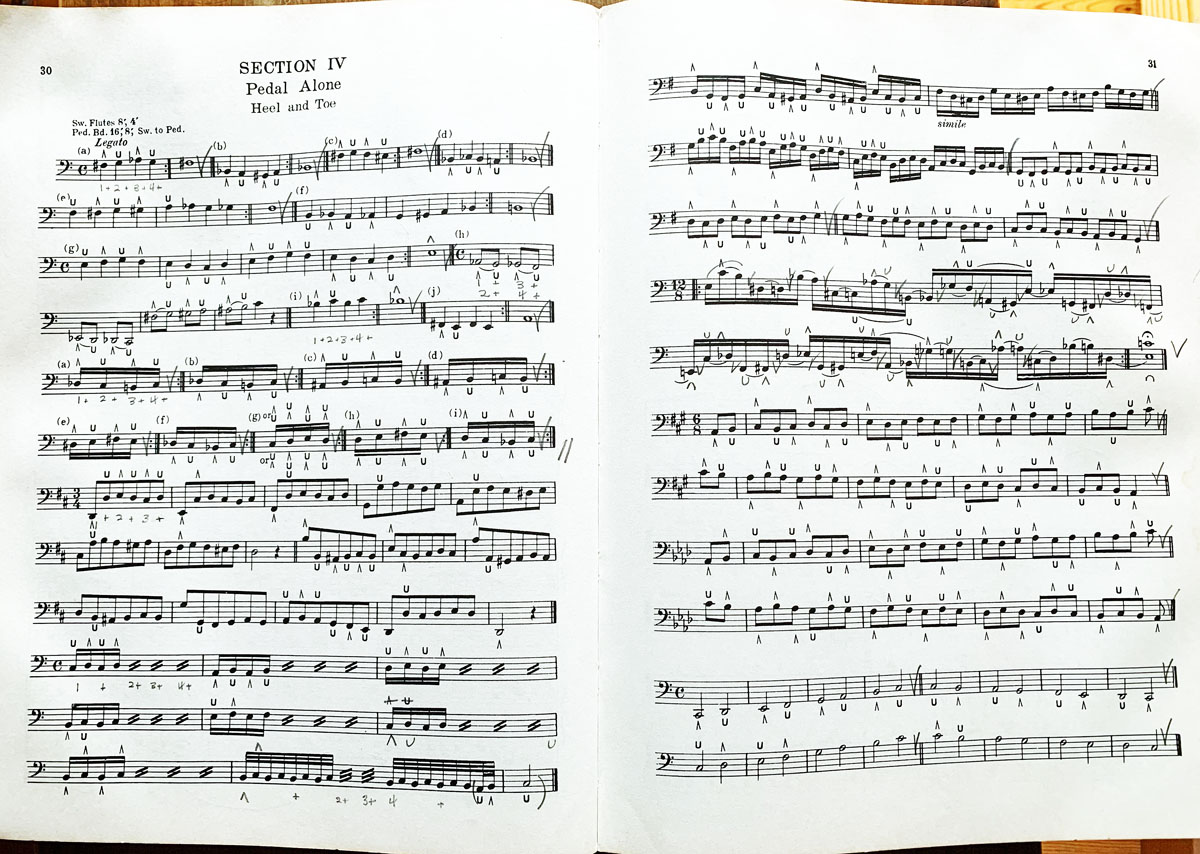

The Technique and Art of Organ Playing was published in 1922. I acquired my copy on Aug. 10, 1965. My copy of the book was lost for years, but in a miracle too complicated to describe, and through the help of a friend, the book found its way back to me. There are many pencil marks in the book, most of them from my first organ teacher, Lillian Conrad. The meticulousness of the fingering and phrasing, and the left-right heel-toe handling of the pedal work, impress the daylights out of me today. My organ technique is limited (especially now that I no longer practice regularly), but the quality of my early training was superb. As for organ-playing technique, I’m quite sure that it has not changed since 1922 — or since the time of J.S. Bach, for that matter.

⬆︎ The 1961 English edition of the Larousse Gastronomique. Click here for high resolution version.

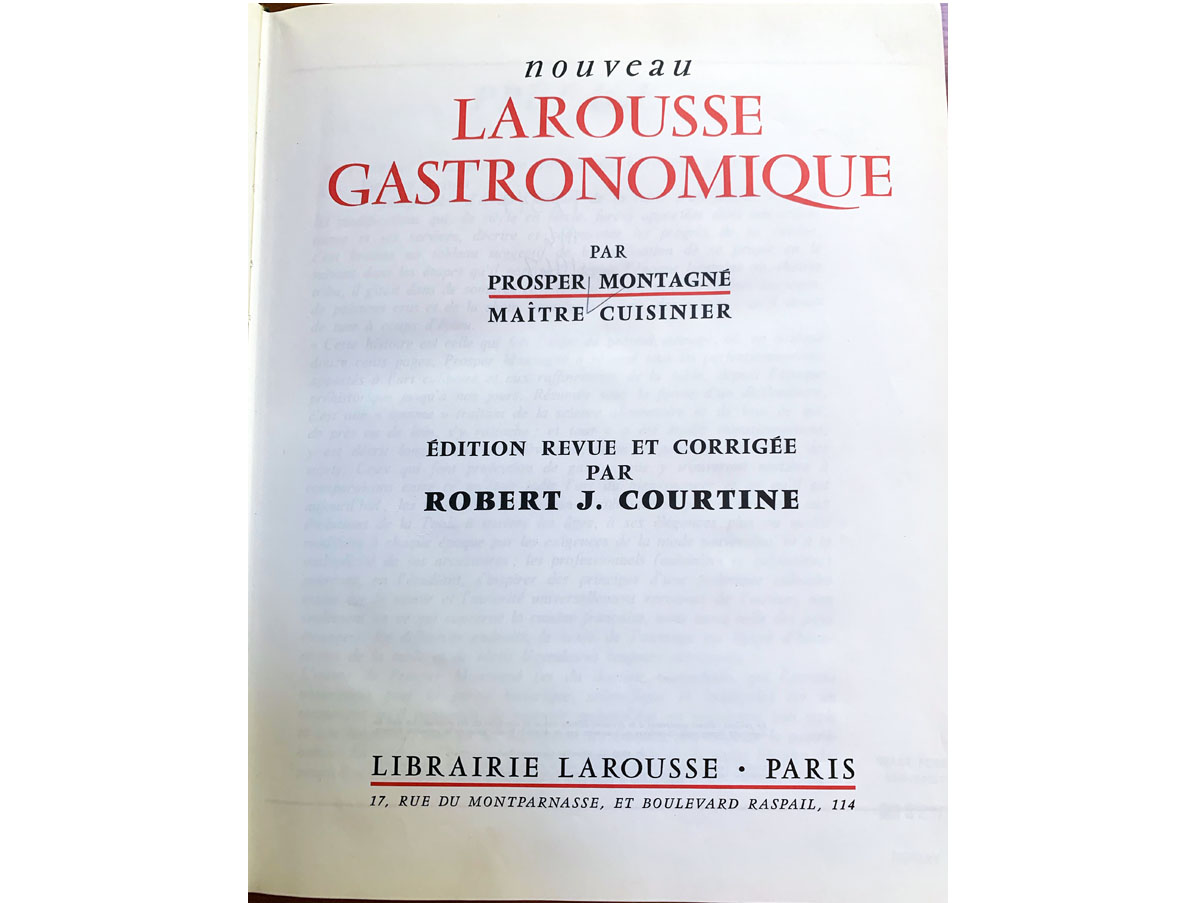

⬆︎ Click here for high resolution version.

⬆︎ Click here for high resolution version.

⬆︎ Click here for high resolution version.

⬆︎ Click here for high resolution version.

⬆︎ Click here for high resolution version.

Somewhat off the subject, but the markings on the page above bring it all to mind:

When I was still a teen-ager, my fingers absorbed the rules for playing repeated notes in four-part hymns on the organ. It’s something that I no longer have to think about; my hands just know. The technique for organ is different from that of the piano, since organ sounds are sustained and piano sounds are not. (Well, not exactly, regardless of what you do with the piano’s sustain pedal.) Here are the rules for playing hymns on the organ, keeping in mind that the soprano and bass are the outer voices and the alto and tenor are the inner voices:

• All repeated notes in the soprano are struck.

• All repeated notes in the bass are tied (except at the end of a phrase).

• When a full chord is repeated identically, strike the three upper voices, and tie the bass (except at the end of a phrase).

• When a full chord is not repeated identically but the tenor or alto or both are repeated, tie them.

Rules like the above have a great deal to do with why poorly trained organists, or good pianists with no organ training, cannot play hymns well. Other common flaws in poor hymn playing are poor phrasing and failure to keep a steady beat. I’m off the subject of books here, but some people probably will Google their way into this. So while I’m on the subject, I’ll add this: Phrasing is critical when the organ is accompanying a congregation. You must give the congregation time to breath between phrases, with a slightly longer breath between verses. Nothing is tied across phrases. All voices break. You cannot rush a congregation that is “dragging” the tempo, as congregations are said to do, by hurrying through the musical phrases. If you give the singers the tempo in the introduction and hold the tempo yourself, they’ll stay with you to the end — if you give them time to breathe.

By the way, since it was published in 1922, The Technique and Art of Organ Playing is now in the public domain.

When I saw this, I immediately knew you were referring to the Dickinson organ method which I cut my teeth on. Later, another teacher moved me to the Gleason method. And I studied in Europe for two years with a protege of Germani so yet another method! Then in grad school reading treatises by Quantz, CPE Bach, etc. So much work but a lifetime of joy from music making. Thanks for a trip down memory lane.