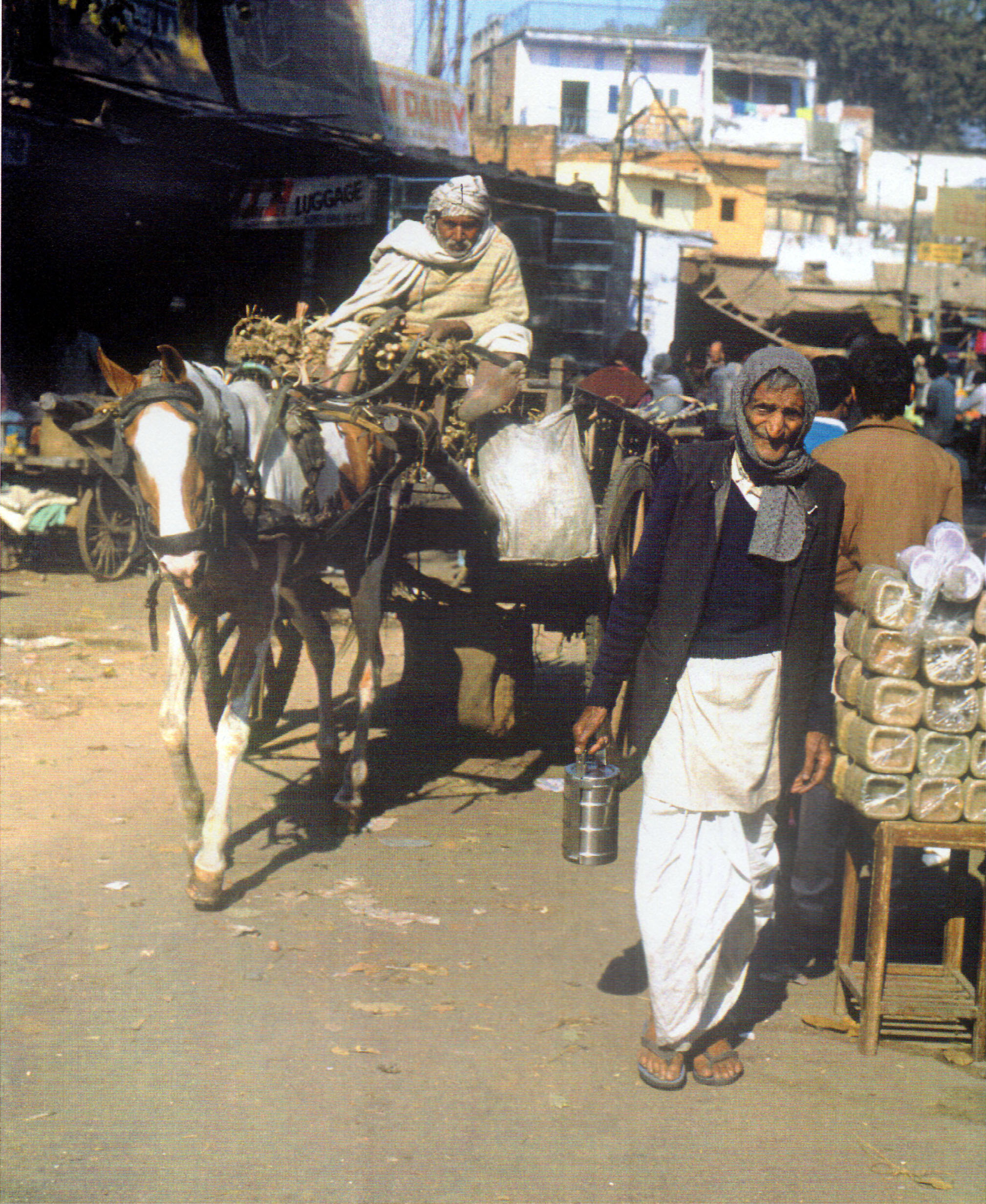

Recently, while rummaging in an old cedar chest that was being moved to the attic for storage, I came across my photographs from a trip to India in December 1994. The photo above particularly catches my eye. I took the photo in the Main Bazaar of Delhi’s Paharganj district (which is just across from the train station and a short tuk-tuk ride from Connaught Place). It’s interesting to look at what the photo says about India’s economy (which I suspect hasn’t changed all that much since 1994).

Notice how skinny the horse is. Animals don’t have very good lives in India. Look at the horse’s harness. It’s well used, but it appears to be of good quality. Look at the wagon. It has big wheels and rides high. It must have been built for bad roads, roads that probably are very muddy in monsoon season. It could be firewood on the wagon, but it also could be roots that are used for some purpose — maybe seasoning, or medicine. I tend to doubt that it’s firewood because it’s all so small. There is no shortage of big trees for firewood, even around Delhi. Notice that the man’s feet are bare. My guess would be that the man driving the cart has driven the cart into Delhi from some nearby rural area, for the purpose of selling these roots. Notice the bags hanging on the wagon. I have no idea what’s in them. Though the man is poor, he owns a horse and wagon. For a person of his caste, that’s probably a big deal.

Now look at the man carrying the stainless steel cylinder. What do you suppose is in the container? I’d guess milk, or maybe oil, but of course I don’t really know. The man is wearing a white apron. I’d guess that he is a vendor in the marketplace, that he sells food, and that the cylinder contains one of the ingredients that he uses to make whatever food he cooks and sells in the bazaar. [Update: See comments. A reader has identified the container as a tiffin.]

Notice the table in the far right of the photo with the bags of merchandise stacked on it. If you buy food in the marketplace, you see what those things are for. They’re little plates, and they’re made from leaves that are somehow pressed into bowl shape, using some sort of low-tech manufacturing process. My guess would be that it’s done with steam and some sort of press.

You can buy all the necessities of life in New Delhi’s Main Bazaar. It has been 25 years since I was in Delhi. At the time, there was no sign of any corporate presence in the bazaar. It was all local enterprise. It’s a beautiful economy, actually. It’s a subsistence economy, but you can buy everything you need to live. For the sellers, it’s a livelihood. It’s all local. I don’t remember even seeing any trucks in the market. It was mostly human and animal traffic.

All markets in all places surely pass through this level of development. When, do you suppose, did we leave that behind here in the United States? Clearly, in 18th Century America, our markets operated at that level. Here, for example, is an article on market days in colonial Williamsburg. My guess is that, even in the 19th Century, we Americans were moving more toward a store-based, merchant-based economy, with fewer people meeting for market days to trade directly with each other. And, of course, by the time automobiles came into the picture, it was all over.

When I was a child in the 1950s, the rural countryside was dotted with country stores. They largely sold commercial brands, brought to the store by distributors’ trucks. Many of these old storefronts, mostly abandoned now, are still standing, though a few have managed to stay in business.

There has been a major new change in the last 15 or so years, though, brought to us by corporations and globalization. First it was Walmart that started bringing cheap Chinese imports to rural Americans. But now the dollar stores are cutting into Walmart’s business. The dollar stores (for example, Dollar General) are now all over the rural countryside the way the old country stores used to be. The dollar stores, ugly as sin, sell everyday items that cut down on trips to Walmart. I confess I sometimes go to Dollar General stores, when I need something like cat litter or cleaning supplies. Watching people check out is terrifying to me. Many people, obviously, buy their groceries there. They feed their families on food bought at Dollar General. Everything is processed, and there is no fresh food at all. It’s all about carbs and meat and sugar water.

So, who has the advanced economy? My answer would be India, by far! Just think about it. Americans who, relatively speaking, are as poor and low-caste as the man driving the cart in the Delhi bazaar now drive their trucks and beat-up old cars to Dollar Generals, where they exchange the money they got from their degrading corporate jobs for cheap foodstuffs shipped in from the global economy, much of it from China, where it was produced by peasants brought to the city by corporations to work degrading corporate jobs. Corporations do all this, and what enables it is the cheap fossil fuel that makes it economically feasible to ship that stuff halfway around the world. Whereas in the Delhi market, the shipping is limited to the range that a horse and cart can manage.

The poor Americans who work the degrading jobs and who spend half their paychecks at Dollar General (and the other half on cars and gas — Trump voters) seem to never question the insanity of how it all works. They are an incurious and passive lot, as willing to get their religion and politics from dumb-ass country preachers as to get their bread and milk and sugar water at Dollar General. It’s only we liberals who question this corporatization and globalization and who dream of local markets. It’s only we liberals who are horrified at how the Republican Party is doing everything possible to hand everything over for further corporatization, including education. It’s only we liberals to whom the word corporate and corporatized are ugly words. As for the Trump voters, they don’t know what hit them, and they probably never will. They get slave wages for their degrading corporate jobs, and they scrape by, handing their entire income back to corporations for bad food, sugar water, cigarettes, trucks, and gasoline. The country folk could grow their own vegetables, but they don’t. They don’t eat vegetables anymore. They prefer the stuff from Dollar General, which is exactly how the corporations want it.

It’s interesting to analyze my own budget to try to come up with a rough index of how dependent on corporations I am. I’m plenty dependent — we all are. I don’t have a mortgage, or any debt, so the financial corporations don’t get anything out me. In fact, I actually make money off my bank by using a “rewards” card for purchases. I drive a 16-year-old Jeep (though I drive it very little — it’s the abbey’s beast of burden) and a leased Smart car. Because I don’t drive much, and because the car gets about 48 miles to the gallon, the oil companies don’t get much out of me. My total transportation and beast-of-burden cost is significantly less than what Trump voters pay just for their cigarettes. Though property taxes and homeowners insurance are a significant chunk of my budget, most of the money that I pay out to corporations goes for food. Whole Foods gets most of that. Still, most of what we liberals eat comes from smaller farms and smaller companies such as Arrowhead Mills, Hain Celestial, Spectrum, or Eden Organic. I buy only California wines and olive oil. I do not do business with the big agricultural monopolies.

I live in an agricultural county in which, even a hundred years ago, subsistence farming was the rule. The county has not changed all that much (except for the cars and Dollar Generals). The land is sparsely populated, with a sustainable land-to-people ratio. The fields and pastures are still here. Many of the barns are still standing. We could easily provide most of our food, but we don’t. It was in no way necessary for us to turn our basic needs over to global corporations. Why did we do it, while the local fields lie fallow, and the people who could be working the fields are unemployed? Would they really rather fry chicken at Bojangles than grow beans and corn? How I would love to drive a horse and wagon to Danbury once a week to trade with my neighbors! Why don’t we do that anymore? Is there any way to get back to that? I’m a liberal. I dream. If you think about it, my dream is a conservative dream about a past that was better and that we ought to return to. But our politics is as insane as our economy, and so my anti-corporate dream is seen as radical and liberal. Further corporatization is seen as conservative. Go figure.

Good post. Consider reading a book called Retopia by John Michael Greer. It’s about a society that decides to reduce their dependence on technology.

I think it’s likely we’ll be relocalising to some degree in the next decade or two, just through necessity.

I’m so afraid you’re right, Chenda. That’s why I live where I live — a sparsely populated place with agricultural infrastructure. Churches and the Republican Party have ruined most of the old people, but there is hope for the young.

One more incredibly efficient method Indians use is represented in that stainless steel container the man in the picture is carrying. It’s a tiffin. A reusable, efficient container with 4 or 5 separate stacked containers packed by the homemaker each morning and delivered fresh and hot by the system of dabbawalas, to the husband in his workplace. It’s filled with healthy, home cooked food made from fresh ingredients and cooked exactly as he would like it. It’s such an efficient system that business educators from all over the world travel to India to study how it works.

Wow, Karren, thanks for knowing about that and for passing it on.