Paul Krugman’s column today is about crypto currency, “Crypto Is Crashing. Where Were the Regulators?” But my subject here isn’t crypto currency. Rather, it’s the many, many ways in which people allow themselves to be deceived, and the many, many ways in which people try to deceive us.

As for how people allowed themselves to be deceived about crypto currency, Krugman writes (the italics are mine): “The way I see it, crypto evolved into a sort of postmodern pyramid scheme. The industry lured investors in with a combination of technobabble and libertarian derp.”

That started me thinking about derp. It’s a beautiful word that almost defines itself. Krugman uses the word fairly often, probably because economic derp is so common. But there are many kinds of derp. Our lives are a minefield of derp. If our defenses against derp are weak, then we’re going to get things wrong. When we get things wrong, we are vulnerable to misjudgments that can lead to all sorts of trouble. Did you receive a phishing email and fall for the derp? Oops. There went your bank account. Did you drink bleach during the Covid lockdown? Oops. There went your esophagus, your stomach lining, and half of your intestines.

Epistemology — the philosophy of how we know things, how we discover new things, how we disprove things, and how we correct our errors — is very complex and very well developed. More than once in my life I’ve been accused of wanting to be right, as though that is an insult. Perhaps it’s thought to be an insult because wanting to be right is assumed to be about policing the errors of others. But that’s not it at all. It’s about applying good sense and skepticism to what we allow into our heads. It’s about making good decisions. It’s about not being prey in a world of derp. And yes, whether you want to call it policing or not, it’s also about saying that’s derp when confronted with derp.

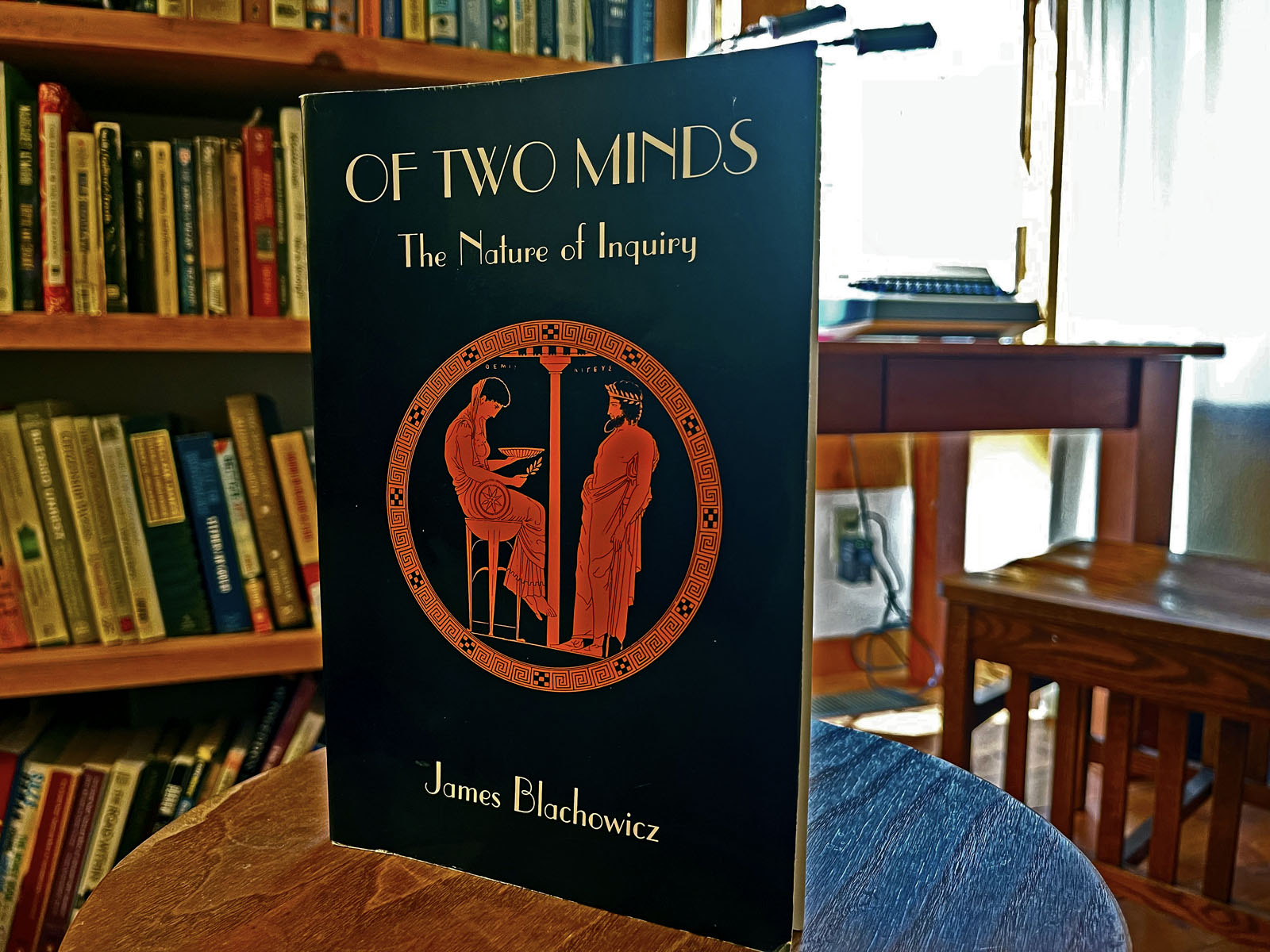

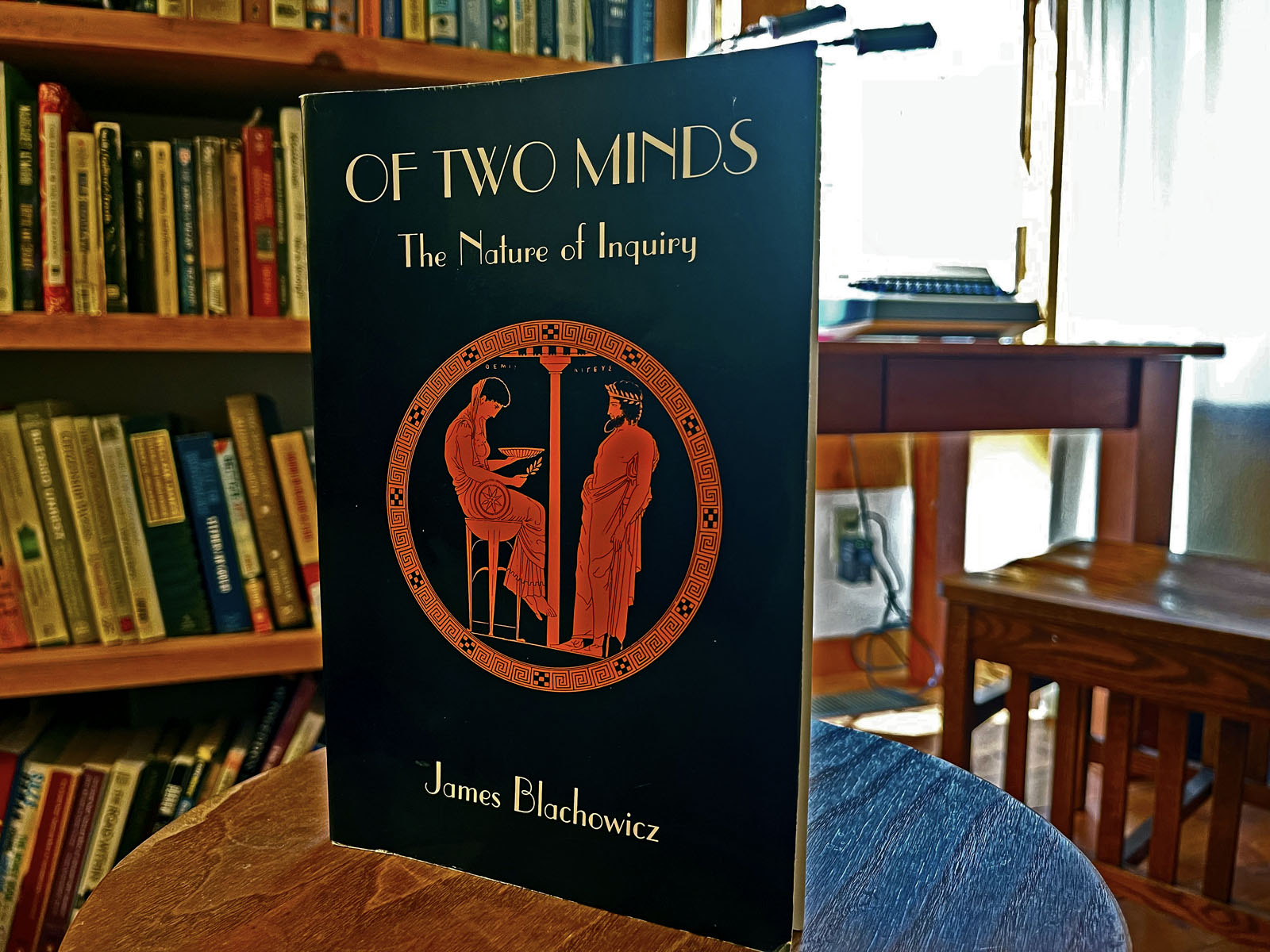

I often read books that go over my head and that are more than I can understand. Usually, though, that’s worth the effort, because something can be gleaned. There are three subjects in particular about which I would like to know a great deal more but which are subjects that go over my head: physics, mathematics, and philosophy. The over-my-head book that was most recently on the nightstand is Of Two Minds: The Nature of Inquiry (James Blachowicz, State University of New York Press, 1998). I bought this book a while back because I’d come across references to the book which suggested that Blachowicz delivered a whipping or two to Karl Popper, whom many mongers of the smarter sort of derp take to be the last word in epistemology. I have learned the hard way that when someone is hectoring us with derp and makes a reference to Karl Popper, our derp detectors should light up.

Before, say, the days of cable television in the 1980s, it was fairly expensive to dispense derp. Historically people certainly found ways to do it. Pamphleteering, for example, which was often anonymous, is an important part of American and British history. But few people could afford the printing costs. But we now live in an era in which dispensing derp is nearly cost-free. It was cable television, for example, which brought us television preachers. The derp quickly created a lot of rich preachers. A decade later (1996), cable television brought us Fox News. When derp comes via email, we call it spam. And then came Facebook and all the other low-cost distributors of derp, derp, and more derp.

I think it’s unfortunately true these days that many people — if not most people — just don’t have the ability to defend themselves from derp. Some derp has become so sophisticated that having a Ph.D. is insufficient protection, at least where there are underlying susceptibilities. Some intelligence is required to detect derp, the more intelligence the better. Some education is required, the more the better. But character flaws also make people susceptible to derp — authoritarianism, narcissism, meanness and prejudice of every type, and (it’s a biggy) a craving for religion. Millions of people live in the trifecta of derp: They’re not very smart, they have weak educations, and they’re moral morons. Such people live in an alternate universe of purest derp, with just enough contact with a rational world to get in out of the rain.

I’ve hastily come up with a list of some categories of derp. If you’d like to add to the list, please leave a comment.

• Libertarian derp, with a hat tip to Krugman. There are well-funded think tanks that develop libertarian derp — for example, the Cato Institute. Billionaires and techno-utopians such as Elon Musk use the media to dispense libertarian derp.

• Right-wing derp. We’re utterly inundated with right-wing derp these days. It may be as close as your dinner table. Unless you’re off the grid or something, there is no escaping it.

• Centrist derp. The mainstream media are full of centrist derp. For publications such as The Atlantic, it’s a business model. Here I owe another hat tip to Paul Krugman, who I believe came up with the term “radical centrist.”

• Leftist derp. This is not nearly — not anywhere near — as common as centrist derp would have us believe. But it does exist. Think Glenn Greenwald or Jill Stein, the kind of leftists who are aligned with Russia.

• Religious derp. My personal epistemological view is that all religion is derp. But there are of course many religions and many degrees of religious derpiness.

• Marketing derp.

• Sucker derp. Think spam, phishing scams, pyramid schemes, and anyone who uses any form of derp to raise money.

• Doomer derp. You’d better buy your guns and ammo now to protect your family from the civil war that is going to start any minute. Trans athletes are going to groom our children and bring down the wrath of God on our once-great nation!

• Sentimental derp. Someday you, too, will find true love.

• Techno-utopian derp: Social media will bring us all together! Technology will save the planet! Artificial intelligence will save us from our ignorance! The meta world will be better than the real thing!

• Economic derp. Cutting taxes makes everyone better off and increases government revenue!

• Hero derp. I can’t stand the sight of Elon Musk, but he has millions of fan boys, most of whom, I’m pretty sure, also consume libertarian and techno-utopian derp.

• Distraction derp: Flood the zone with shit! Antifa did it! But her emails!

• Elitist derp: The New Yorker.

Part of the problem is that so many people love their derp. Without derp, their lives would be empty. And yet derp is the very thing that makes their lives so pathetic.