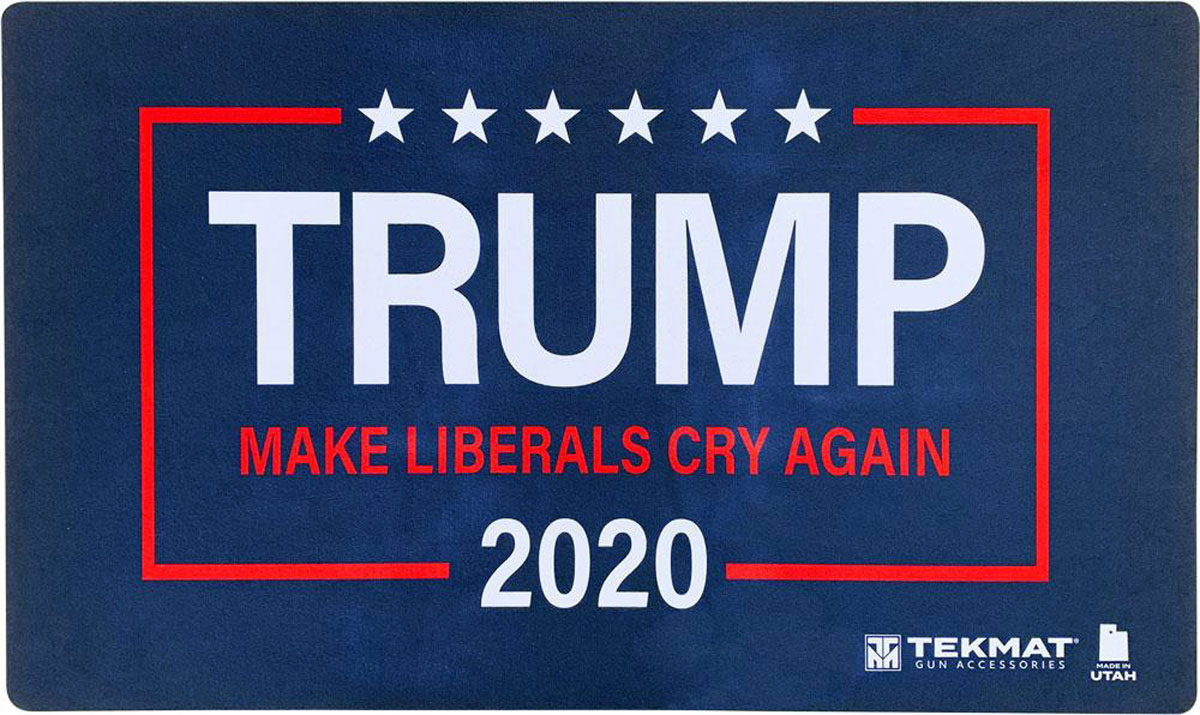

This gun-cleaning mat sent out as a freebie to gun-supply customers is pretty clear about how the Republican Party retails Trumpian meanness to its base. Source: Reddit

We are being terrorized, aren’t we? Yet again yesterday, in a press conference, Trump said that any election he loses would be fraudulent and that he won’t commit to leaving office. This terrorism by Trump and the Republican Party is not likely to let up, even after Nov. 3. They want us to be demoralized and just give up.

In 2020, I think that there are reasons for optimism, though. During the 2016 election, the media and the commentariat largely were bamboozled by Trump and fell for Trump’s shtick, taking refuge in centrism and notions of objectivity, thus giving Trump a free ride and suppressing the story of what Trump really is. The New York Times, actually, is still trying to cling to what it sees as journalistic principles and still tries to write about Trump as though the American political situation is still normal. But mostly the media now get it. (I am excluding, of course, right-wing propaganda machinery such as Fox News.) Just in the past few days, there have been several important pieces describing with great clarity just where we stand and how much danger we are in. All these are must-reads:

• The most important of these pieces is in the Atlantic: The Election That Could Break America: If the vote is close, Donald Trump could easily throw the election into chaos and subvert the result. Who will stop him?

• Vox has a very good piece on just how abnormal the Republican Party has become: The Republican Party Is an Authoritarian Outlier

• At Politico: Trump Is an Authoritarian. So Are Millions of Americans.

• A piece at Time describes the economic background on what’s really behind the Republican Party’s desperation to stay in power. It’s to hold on to the system of gross inequality that allows the super-rich to keep getting richer: The Top 1% of Americans Have Taken $50 Trillion From the Bottom 90%—And That’s Made the U.S. Less Secure.

In the past four years of Trump, book after book and article after article have analyzed and accurately described just where America stands today. To try to put it as briefly as possible: A minority party (the Republican Party), desperate to cling to power even though its agenda is regressive and unpopular, is willing to compromise American democracy to stay in power. The Republican Party’s intent is to eliminate real opposition by any means it can get away with (though with a pretense of legality if possible) and to entrench itself as an unchallengeable ruling party with a strongman authoritarian leader: Trump. The party is controlled by the agenda of the 1 percent, but the party has strong (but minority) populist support from the most disaffected and manipulable element of the population. There is nothing new here. If the Republican Party succeeds in subverting the American democracy, it won’t be the first time that a democracy has been lost. The Republican Party has many examples to work with on how to go about putting down a democracy, and they are indeed following a well-studied playbook. (I am at present reading a book on this subject: Authoritarianism: What Everyone Needs to Know. I’ll have a review of it soon.)

We have a huge body of work from academics, journalists, and government experts on where we now stand and what Trump might do. But, as far as I know, no one has yet written about how we get rid of Trump if he steals the election.

So, as a thought experiment, let’s think about the worst case. What if Trump actually succeeds in stealing the election and manages to stay in office after inauguration day on Jan. 20? Let’s try to game it out.

If there is a Trump-Republican takeover, then I can’t imagine that a Trump regime would be able to achieve anything resembling stability. Trump would find himself surrounded by powerful forces working day and night within the tatters of democracy to take him down. Trump has never had majority support. If current polls are valid, he will lose the popular vote in this election by 8 to 10 percent. Except to Trump’s base, who believe what they’re told, the treachery of Trump and the Republican Party would be unmasked. A majority of Americans would be enraged and would demand a restoration of democracy. The Trump regime does not have the machinery in place to impose the level of repression that would be required. They might resort to terror by making examples of some who resist, but I suspect that that would only make things less secure for Trump by further enraging the opposition. It would be difficult or impossible to make a takeover look legal — though of course they will try, claiming as a last resort that it was for the good of the country. Civil servants would resign en masse. Even though Trump has installed incompetent loyalists in government departments (though William Barr at the Justice Department has shown considerable competence at twisting the law) there just would not be enough low-level loyalists to keep the wheels of government turning. Any who’d be willing to try would be unqualified and incompetent and in it for what they could steal. The incompetence and churn and corruption would cripple government services, and people would soon notice (as they already noticed with the U.S. Postal Service). If the Social Security checks ever got held up, the music would stop. Corporate America would look for ways to get involved. Corporate America doesn’t want to be taxed, but business depends on stability and predictability.

American instability would lead to turmoil in global financial markets and the global economy. America’s allies and even barely friendly economic partners such as China would act not only to protect their own economies and their own interests, but also to impose sanctions against the United States. If there is anything that authoritarian governments hate, it’s economic sanctions (ask Vladimir Putin). If domestic turmoil alone didn’t crush the American economy, then international sanctions would. Trump in his foolishness seems to have lost the confidence of the American military. After a coup or takeover, one of the tests of who is in control is whom the military will take orders from. I seriously doubt that Trump and the Republican Party would be able to cow or to even buy off the American military. Some authoritarian governments are highly competent — Russia’s and China’s, for example. But no amount of help from Vladimir Putin would be sufficient to make up for the incompetence of the Trump regime or of Trump’s loyalists in the U.S. House and Senate. They would bungle everything. There certainly would be disorder in the streets, and that disorder could start to look like civil war. But disorder in the streets would not help to keep a Trump regime in power, no matter how well-armed Republican brownshirts might be. Disorder in the streets does not prop tyrants up. It takes them down.

One of the points that Erica Frantz makes again and again in Authoritarianism: What Everyone Needs to Know is that authoritarian leaders are the most dangerous when they are afraid of punishment on leaving office. That is probably the No. 1 reason why Trump has become so dangerous and so willing to go to extremes to try to stay in office. He’s going to prison, and he knows it. Once he leaves office, no longer with the power to hold off the legal nooses that are tightening around him, his life is over. If he’s smart, he and his family will just get on his plane (which I saw last year parked in plain sight at La Guardia airport), and fly to Russia. There is no future for him in the United States other than an ugly one.

One thing that greatly puzzles me is why the Republican Party has allowed Trump to get away with pushing things this far. A rational Republican Party would have cut a deal with Trump to get him out of the way, to keep the Senate, and to prevent Trump from taking the party down with him. Trump probably would have been able to negotiate some immunity for his crimes. Several pieces have been written about what senators say about Trump in private, though in public those same senators are Trump loyalists. It seems they’ve got Trump’s number, yet they’re siding with Trump and violating their oaths to the Constitution and to the law. Eventually, journalists and historians will figure that out. But I’m afraid that it’s one of the things that we won’t really know until after Trump has been put down and we can trace the money and the kompromat.

In short, I cannot imagine that a Trump-Republican takeover would last long. Once the takeover was put down, I think that the United States would return to democracy, with many lessons learned and many fixes to the law (and maybe even the Constitution) to ensure that it doesn’t happen again.

Update: Some Republicans are distancing themselves from Trump’s threat (but without mentioning Trump). But some Republicans, such as Sen. Thom Tillis of North Carolina and Rep. Matt Gaetz of Florida, are using it as just another opportunity to show how vile they are. Republicans condemn Trump’s refusal to commit to peaceful transfer of power.