Whether we approve or not, Amazon is now important for rural people, just as the Sears catalog was many years ago. We recently put up new signs to help keep the Amazon trucks from getting lost.

I usually think of myself as a hermit, hiding down in the forest, ruled by a bossy, devoted, and needy cat. But when I think back on the eleven years I have lived here in the woods, it’s remarkable how much social work I have done, just because I looked around this little, red, poor, beautiful, unspoiled, undiscovered county in the Appalachian foothills and saw how much social work needed to be done. It also is remarkable how much help, and how many allies, I have had.

Stephen Sondheim:

You move just a finger,

Say the slightest word,

Something’s bound to linger,

Be heard.

No one acts alone.

Careful, no one is alone.

At first it was just me, transplanted (from San Francisco), disoriented, culture-shocked, with an overwhelming amount of work to be done to make a home where there was nothing but woods. I lived in a camping trailer for a year while building the house, and as soon as the trailer had all the hookups necessary to provide for myself and a cat, Lily the cat came to live with me. About a year later, Ken appeared. (I had emailed him after reading his beautiful viral piece in Salon about living in his van while in graduate school at Duke University.) The energy — literary and otherwise — that Ken brought to the project as he lived here on and off for the next 10 years made a huge difference.

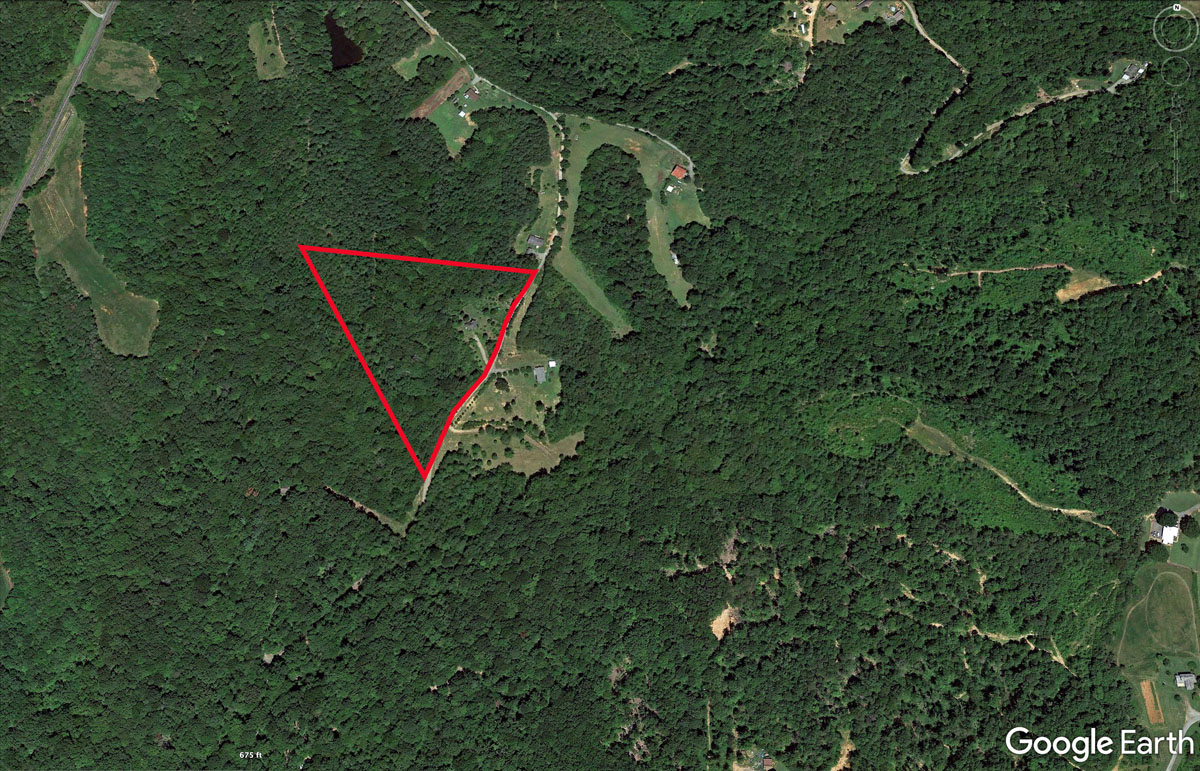

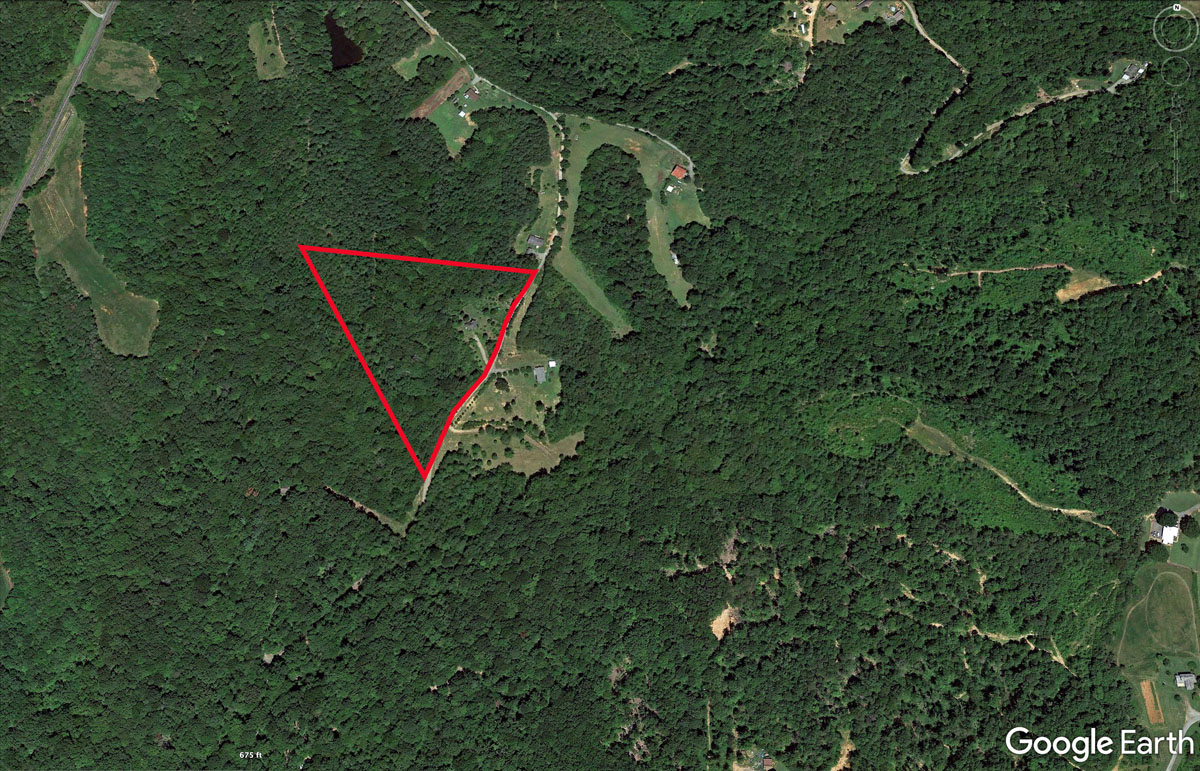

For some context and perspective, I recommend the piece that Ken wrote earlier this year for the Wigtown Book Festival, Letter From the Heartland. Also note the satellite photo below, which shows the little village-in-the-woods in which I live, with the abbey’s piece of the woods marked with red.

I first heard Stokes County’s cry for help in 2012. Republicans had taken over the North Carolina legislature, and they naturally thought that sacrificing a couple of rural counties for fracking was a beautiful idea, since fracking had done such wonders in poisoning the people of Pennsylvania. Before my time here, there had been a previous environmental emergency in the county when a chip plant was proposed, the object of which, I assume, was to take our trees and turn them into fuel and building products, polluting in the process and overloading our winding roads with heavy trucks. Some veterans of that fight (which they won), quickly got an organization called No Fracking in Stokes up and running. I am proud to say that I joined that effort early on. Not only have we not been fracked, the organization was so effective that it became quite prominent in the anti-fracking movement.

For better or for worse, I was soon recruited for the executive committee of the Stokes County Democratic Party. Then I was elected county chair. I was in that position for almost six years, until I resigned recently for reasons that aren’t worth going into. The 2020 election was exhausting, and I hope it will be my last election as a local political operative. At the county level, we lost, big (not that we expected anything else). Trump won this county with 78 percent of the vote, so there is a lot of work to be done. In the future I hope to work much closer to home. But there was much to be gained from six years as county chair: I got to know lots of people, and I learned a lot about this county, including things that some people didn’t want me to know.

If I were filthy rich, I’d have the means to do what the filthy rich do to buy seclusion and security. I’d buy hundreds or thousands of acres and put a fence around it. But because I’m not filthy rich, and because my holdings in land are small, I depend on my neighbors for buffer and for security. That’s one reason why village-building is so important (and always has been): Mutual security, and a sharing of skills, tools, and infrastructure.

I can take credit for only a portion of the village-building that is happening here in this neck of the woods. Most of the credit goes to the man whom Ken calls Ron in Ken’s article for Wigtown. Just as Ron doesn’t fully understand why I’m a liberal, I don’t fully understand why a man with his intelligence, social skill, and generosity is a Republican. But we don’t waste time on national wedge issues, because we have plenty of work to do here in the woods.

For example, my tiller had died, and a $90 visit to a small engine shop failed to fix it. Ron suggested that I buy a new carburetor (a mere $14 from Amazon). Yesterday Ron installed the carburetor for me while I handed him tools. Now the tiller runs like new. He has helped with so many projects here that I wouldn’t be able to list them all. I do my best to return the favor with things that I know how to do, such as programming his (and the neighbors’) radios and giving advice on appropriate antennas and how to install them. They heat with wood, so when there’s firewood to be split and stacked, I can help.

Ken has written quite a lot about private property (This Land Is Our Land) and how much he hates no-trespassing signs. There are far too many no-trespassing signs down in these woods. But I’m pleased to say that many of the signs, and much of the purple paint, is fading as a more village-oriented attitude takes root. Ken and I realized long ago that reforming the neighbors’ attitudes on property would be a longterm project to be handled tactfully. I’m pleased to say, though, that the woods are increasingly being treated as a commons, as they ought to be. When a tree goes down in a storm, the question is not whose land it’s on but who needs firewood. And we’ve all become rather proud of our hidden network of trails in the woods, which Ron maintains. When he asked to build a wooden bridge over the stream where the neighbors’ right-of-way crosses abbey property, of course I said yes. My mailbox is half a mile away, and the best walk to the mailbox goes over the bridge and through the woods.

Ron’s organizational skills have turned this little village into a Neighborhood Watch on steroids. Many of the neighbors now have handheld radios, and Ron and I monitor for calls for help. Help has been needed surprisingly often, such as when a 77-year-old neighbor overturned her ATV on a steep hill and was trapped underneath it in the woods, or when another elderly neighbor had symptoms of a heart attack while in the woods hunting turkeys. Everyone has different skills and different kinds of tools. In a village, those skills and tools are available to all. When a culvert washed out a few weeks ago under the road down in the bottom (it’s an unpaved private road, and maintaining it is our responsibility), one of the neighbors brought in his Bobcat and fixed it. That same neighbor now supplies us with eggs. The best I’ve been able to offer him in return so far was enough of my wild persimmons to make a pudding. Everybody has a garden, and everybody shares. Power outages, wind storms, washouts from heavy rain, accidents — there’s always something. One of the biggest shockers to me is that, though most of the neighbors identify as doughty hunters, they rarely shoot anything. Instead they’re on the lookout for poachers that might threaten the local deer, many of whom (including the white deer) have names. Just this week Ron called the game warden because somebody was trying to spotlight our village deer. Ron and someone he knows recently did a census of the local raccoon population, using trained dogs. Six or eight raccoons were treed, but none were harmed. They know where the owls live. They feed the fish down in our little creek, from which irrigation water for gardens is available to any higher-elevation neighbors with tanks and tractors (else Ron will haul it for them). They’ve put out the word that, if anybody is trapping surplus opossums, we could use some more here. If Pete, one of the horses up the hill, breaks out of the pasture, I hear about it, and where Pete pooped, on community radio. As Ken’s article mentions, I’m the “comms” guy, because I have an extra class amateur radio license. And, yes, we all know how to shoot. Ron and his dad set up a shooting range down in the bottom, and it’s available for villagers to go practice. The noise is sometimes annoying, but it’s more a weekly thing than an everyday thing.

Increasingly, what I’m seeing here reminds me of what I remember from the 1950s — the traditional skills and infrastructure that make a high degree of self-sufficiency possible, just because people make their livings at home. Yes, most of us here are retired, but we still work. In a way, Covid-19 has done the world a favor by requiring that we rethink how much of our work can be done from home and how our neighborhoods can expand into local pods. I know that we can’t all live in rural villages. But virtual villages can exist anywhere. I well remember how much Hillary Clinton was ridiculed (by Republicans) for her book It Takes a Village. The ridicule says a lot about the madness of our era, when many people are taught by propaganda to ridicule the very things they most need and are lacking, including an honest politics that serves people’s actual needs. If America is ever great again (whatever that means), surely it will be something that grows bottom-up, instead of being sold as a scam, top down. Until that time comes, I consider it a privilege to have so much space around me, and a level of security that I wish everyone could have.

A neighbor’s wood pile. I helped split the wood.

Pete’s and Buddy’s pasture

The backroad to the mailbox

The road descends past the abbey toward the creek bottom.

Helping the neighbors build their watch tower (no kidding) up on the ridge. That’s Ron’s dad on the right.

The founding members of No Fracking in Stokes. I’m in the back. Winston-Salem Journal photo.

Me as county chair with Deborah Ross, who was running for the U.S. Senate

Ken and me, June 2011

A limousine picks up Ken for one of his many television appearances after Walden on Wheels was published. Yes, that’s the famous van.

She who rules

During the month before the Nov. 3 election, a film crew from Los Angeles and New York was in North Carolina to shoot a documentary called Swing State. They spent several days in Stokes County. I helped show them around and helped them decide whom to interview. Here they are interviewing local candidates for the North Carolina legislature. The documentary should be released next year. I was interviewed, too, and probably will make it into the finished documentary.