Kim Davis, an elected county clerk in Rowan County, Kentucky, according to news reports, is continuing to deny marriage licenses today, despite an order by the U.S. Supreme Court that she cannot refuse to do so.

She believes that she is defending her religious liberty and that her religious liberty trumps not only the law, but also the rights of the people in Rowan County, Kentucky, to acquire marriage licenses in accord with the law and their own religious beliefs. “This searing act of validation would forever echo in her conscience,” her lawyers told the Supreme Court. According to the New York Times, she is in her office this morning with the door and blinds closed.

First of all, let’s pull away the mask. Anyone who believes that Ms. Davis’ conscience is kind and conscientious is greatly deceived. She is a hateful, hypocritical (married four times) and intolerant person. She is being used by, and financed by, other hateful and intolerant people for political purposes. After this is resolved, keep an eye on what she does. Michael Savage predicts that she will become well-off and popular on the right-wing lecture circuit.

For the rest of us, she presents a problem that goes beyond the law. The law is clear. But the attitude that truly conscientious people should take toward the hatreds and intolerant mischief of people like Kim Davis is not so clear.

In a post a few weeks ago, in the matter of Cecil the lion, I mentioned John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice, which for decades has been the leading text in the field of moral philosophy. Rawls’ 500-page book includes a section titled “Toleration of the Intolerant.”

“Some political parties in democratic states,” Rawls writes, “hold doctrines that commit them to suppress the constitutional liberties whenever they have the power.” Check. We’ve got that — a Republican party, allied with the Christian right, that is fanatical about the privileges and liberties of the privileged but determined to keep down anyone who would challenge or dilute the privileges of the privileged.

Rawls writes, “Now, to be sure, an intolerant man will say that he acts in good faith and that he does not ask anything for himself that he denies to others. His view, let us suppose, is that he is acting on the principle that God is to be obeyed and the truth accepted by all. This principle is perfectly general and by acting on it he is not making an exception in his own case. As he sees the matter, he is following the correct principle which others reject.”

And yet: “Each person must insist upon an equal right to decide what his religious objections are. He cannot give up this right to another person or institutional authority…. From the fact that God’s intention is to be complied with, it does not follow that any person or institution has the authority to interfere with another’s interpretation of his religious obligations. This religious principle justifies no one in demanding in law or politics a greater liberty for himself….”

In other words, Kim Davis is claiming the right not only to deny people marriage licenses, but also the right to be a religious dictator for the people in her county.

Rawls again:

“Rather, since a just constitution exists, all citizens have a natural duty of justice to uphold it. We are not released from this duty whenever others are disposed to act unjustly…. Knowing the inherent stability of a just constitution, members of a well-ordered society have the confidence to limit the freedom of the intolerant only in the special cases when it is necessary for preserving equal liberty itself.”

I have put the last sentence above in italics because I believe that, setting aside matters of law, that is the moral principle behind the Supreme Court’s ruling — that denying this liberty to Kim Davis is necessary to protect the equal liberty of others.

“The conclusion, then,” writes Rawls, “is that while an intolerant sect does not itself have title to complain of intolerance, its freedom should be restricted only when the tolerant sincerely and within reason believe that their own security and that of the institutions of liberty are in danger…. The liberties of some are not suppressed simply to make possible a greater liberty for others. Justice forbids this sort of reasoning in connection with liberty…. It is the liberty of the intolerant which is to be limited, and this is done for the sake of equal liberty under a just constitution….”

Rawls was writing in 1971, though his book was revised in 1990. Rawls died in 2002. Religionists imagine that no moral framework exists outside religious authority and ancient texts. But most religionists would not know a moral framework even if a modern moral framework saved them from stoning or being burned to death for their own Old Testament crimes.

One of the gross moral flaws and limitations of religions such as Christianity is that they contain no principle for deciding between competing claims other than, ultimately, “I am right and you are wrong, on the authority of the texts.” To make this situation even worse, sects and individuals disagree on the interpretation of the texts, and on what to conveniently ignore in the texts and what to emphasize. They claim liberty for their own arbitrary choices and the end of a stick for everyone else.

As for Kim Davis, I say that she is a common sort — a hateful and vindictive person hiding behind religion. I also say that one of the dangers of religion, and of the authority-loving people who are drawn to it, is that religion tends to produce not good people (though certainly some religious people happen to be good people, not necessarily on account of religion but often in spite of it), but rather that religion tends to produce minds incapable of moral reasoning. Think of Abraham, who was ready to kill his own son because God told him to. As far as I know, the Bible story of Abraham and Isaac is still taught to children to instill the desired concept of unquestioning obedience to authority, and faith.

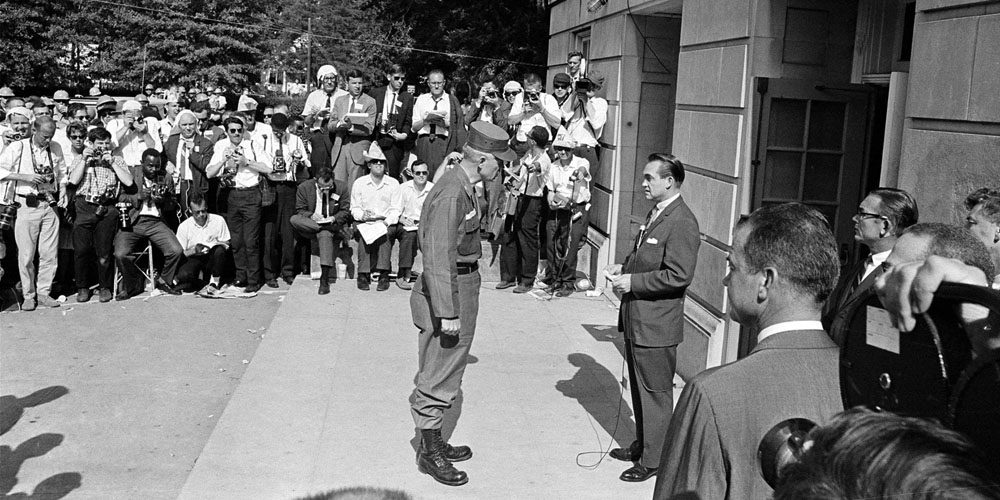

Take your place, Kim Davis, among the vilest moral imbeciles in American history.

UPDATE

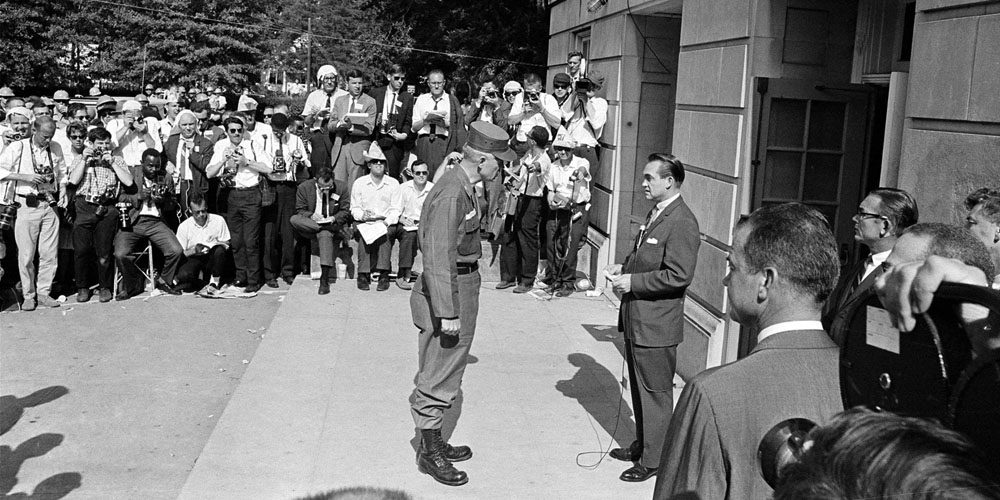

According to news reports today (Sept. 3), a federal judge has ordered Kim Davis to be sent to jail until she complies with the order to issue marriage licenses. While she is in jail, a county judge will issue marriage licenses.

There is an interesting quote in the New York Times story:

“They’re taking rights away from Christians,” Danny Kinder, a 73-year-old retiree from Morehead, said of the courts. “They’ve overstepped their bounds.”

Dear clueless, deranged, and insufferable Christians: You are overstepping your bounds. Your rights to discriminate end where other people’s legal and religious rights begin.