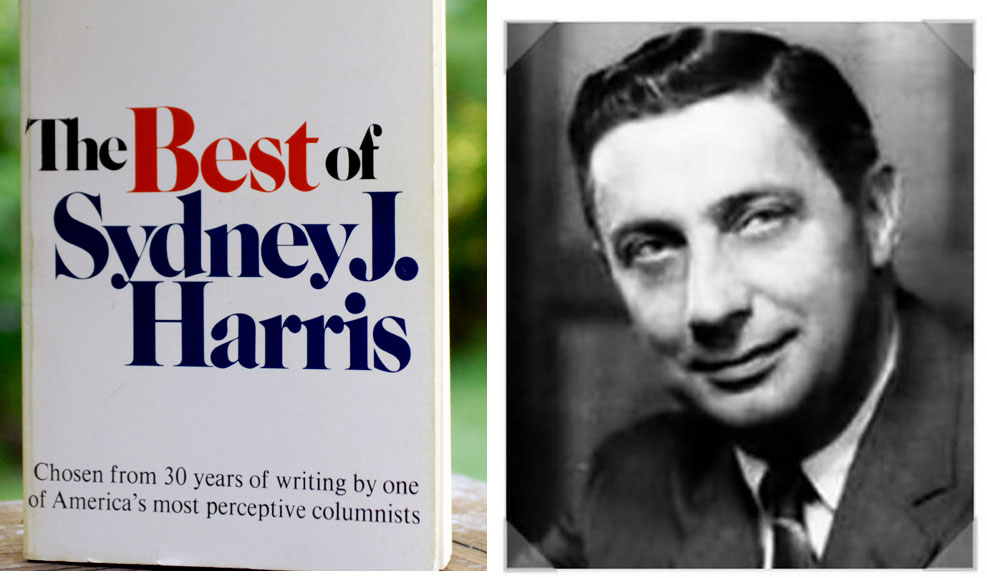

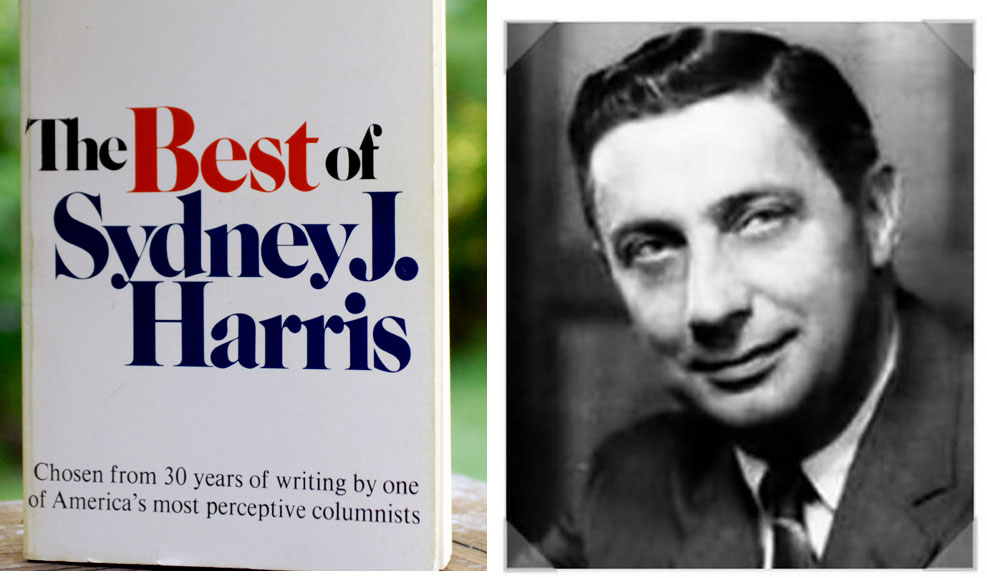

Once upon a time, philosophers could find work with newspapers. There are no such people now. But, back then, Sydney J. Harris was such a person.

Harris (1917-1986) worked for the Chicago Daily News, and, later, the Chicago Sun-Times. For years, he wrote a column called “Strictly Personal,” which was syndicated in 200 newspapers. One of those papers was the Winston-Salem Journal, where I got my first job. When I was college age, not as much was said about liberals vs. conservatives. I only knew that I loved Harris’ columns. He was, of course, a liberal. I should mention that the insufferable William F. Buckley also had a newspaper column in those days, “On the Right,” which was syndicated in even more newspapers — 300. No doubt I read, or tried to read, some of Buckley’s columns, but I have no recollection of it. Buckley would have made no sense to me. His pomposity, and the turgidity of his prose, would have offended me, I’m sure, though Buckley left no lasting impression.

Harris’ columns, I now realize, were formative for me and helped me sort out the political turbulence of the late 1960s and the early 1970s. I think about Harris from time to time, as though he was a mentor. In a way, he was.

Unfortunately, Harris’ books are out of print. His reputation has not carried forward very well into the Internet era. As a kind of memorial, I would like to reproduce here two columns. Both of the columns are taken from the book The Best of Sydney J. Harris, which was published in 1975. Some of the columns, I believe, may go back as far as the 1950s.

We are not fit to colonize space

By Sydney J. Harris

A few days after our successful orbiting of the moon, a friend expressed the hope that this venture would teach people humility in the face of the universe.

“If this helps us realize how vast outer space is, and how small our globe is,” he said, “then it might make us all feel more united as inhabitants of this tiny speck of dust whirling in space.”

This would be a commendable lesson to learn, I agree, but I doubt that we would draw so philosophical an inference from the moon project. Rather, I suggested bleakly, it might lead us in the opposite direction.

Instead of regarding space exploration as a common effort binding mankind together, it is far more likely that we will simply extend our competitiveness from inner to outer space, and look upon the solar system as competing nations once regarded explorations on earth — as places to plant flags, to colonize, to use as economic resources and military outposts.

Unless we make some unexpected quantum jump in our thinking and feeling, we will simply extrapolate to other worlds the same greed and vanity, the same lust for possession and domination, the same conflict over boundaries and priorities throughout the solar system.

What is even more dire, we might also export the contamination of our planet, not merely in terms of wars and prejudices and injustices, but quite physically, in terms of bacteria and viruses and all the assorted pollutions of earth, air and water that are rapidly making our own globe nearly uninhabitable.

Nothing in our history, early or recent, indicates that we are not prepared to despoil other planets as carelessly and contemptuously as we have turned ours from green to gray, from fair to foul, from sweet to sour, in the countryside as well as in the cities — so that even sunny, snowy Switzerland has shown a 90 percent increase in smoke content and turbidity of the air in the last two decades.

We are no more morally or spiritually equipped to colonize other parts of the solar system — given our past level of behavior on earth — than a hog is fit to march in an Easter parade. Our technical genius so far outstrips our ethical and emotional idiocy that we are no more to be trusted to deal lovingly and creatively with another planet than a rhesus monkey can be allowed to run free in a nuclear power plant.

The astronauts are bold men, and the scientists who sent them up are bright men, but they are not the ones who will decide what is done once we get there. The same old schemers will be running the show.

Radical righters are fascists

By Sydney J. Harris

It’s an interesting peculiarity of our social order that while the term “communist” is flung around frequently and often carelessly, its opposite number, “fascist,” is hardly used at all.

In Europe, this is not the case. People have no hesitancy in speaking of the right-wing radicals as “fascists,” for this is what they are. To speak of them as “extreme conservatives” is a foolish contradiction in terms.

And it seems quite plain to me that there are many more fascists and fascist sympathizers in the United States than there are communists and their sympathizers — unless, of course, you care to adopt the fascist line and suggest that everyone who favors staying in the U.N. and retaining Social Security is a Red fellow-traveler.

We seem to be so exercised about communist influence in this country, which is negligible, both in numbers and in appeal to the American temper. Yet, year by year, one sees a fascist spirit rising among the people, although it is called by many other and softer names, and has even achieved a certain dubious respectability in some circles.

There is no reason why there shouldn’t be a fascist movement in this country; nearly every nation has one. But it should be called by its right name, and it should be willing to accept the consequences of its position, as the fascist parties do elsewhere.

It has no business masquerading as “Americanism” or “conservatism” or “patriotism,” when its whole philosophy of man is based on a hate-filled exclusiveness that would shock and affront the conservative American patriots who founded this country.

What is distressing about this movement is the tacit or open support given it by men who genuinely think of themselves as “conservatives,” and who do not understand the implications of right-wing radicalism any more than the German industrialists understood what would happen to them when Hitler swept into power with their support.

Just as Communism always begins with an appeal to “humanity” and “equality” and always ends with inhuman despotism, so does fascism always begin with an appeal to “nationalism” and “individualism,” and ends with a military collectivism far worse than the disease it purports to cure.

These twin evils are the mirror-image of one another. It would be the supreme irony if, in rejecting the blandishments of communism, we fell hysterically into the arms of fascism disguised (as always) as Defender of the Faith.