A detail of the Gundestrup caldron. Source: Wikipedia

The Discovery of Middle Earth: Mapping the Lost World of the Celts. By Graham Robb, W.W. Norton & Co., 2013, 396 pages. Published in Britain as The Ancient Paths: Discovering the Lost Map of Celtic Europe.

Most people — certainly most Americans — never stop and reflect on culture, as though somehow the way we live (and the way we think) today was somehow inevitable. But a bit of travel, a bit of history, and a bit of reflection make it pretty obvious just how arbitrary culture is. Many of us despise American culture. Western culture as a whole is seriously screwed up, though there have been many gifted people over the centuries who have, in large and small ways, managed to make Western culture a little less ugly than it otherwise would have been. But culturally we remain what we are, and some of us don’t like what we are. Our relationship with nature is completely broken. All the magic has been driven out of the world. Our culture and religion have warped our psyches and trampled our instincts (just ask Freud). We are a mess.

A Mozart or a Thomas Jefferson or an Einstein have only a limited effect on culture, the grandeur of their individual achievements notwithstanding. But there are major turning points in culture. One such turning point in Western culture — and I would argue that it was the most important turning point, though it happened 2,000 years ago — was the almost total destruction of Celtic civilization by the Roman armies and the Roman religion. If this had not happened, we in the West would be living in a completely different world today. I think it would be a better world.

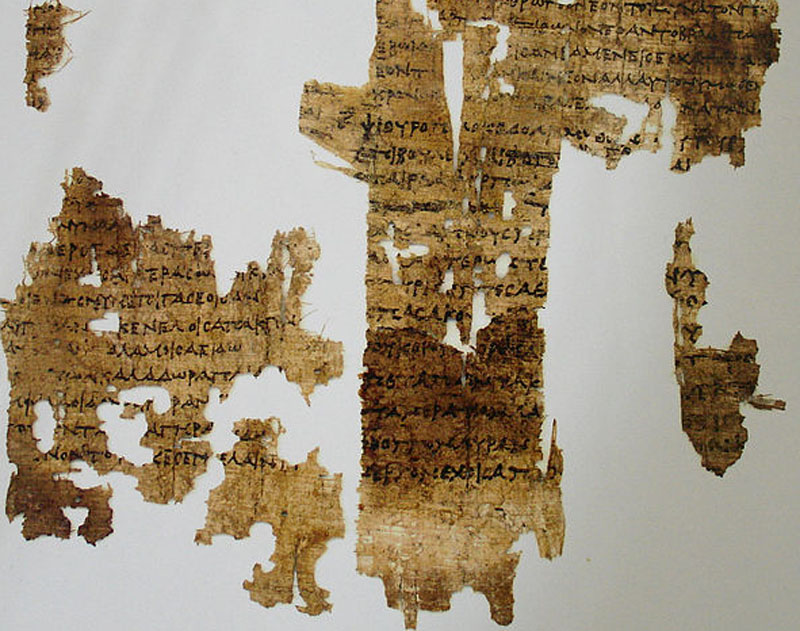

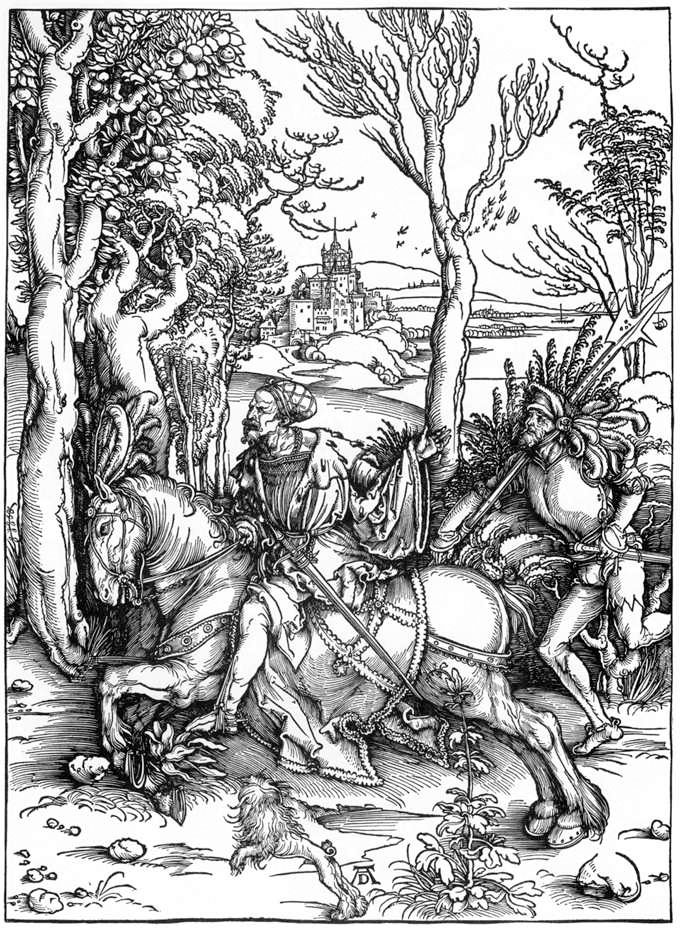

The Roman destruction of Celtic culture — genocide is not too strong a word — was so complete that we know very little about the Celts today. Long after the Roman armies had defeated the Celts in Gaul (France) and Britain and hunted down and killed the Druids, the Roman church continued the work of cultural annihilation. The destruction of the Celts in Gaul was so complete that their language was wiped out. Today, we have two main sources of information about the Celts. The first source is the record left by Greek and Roman historians, including a history by Julius Caesar himself, who spent several years away from Rome with the army, waging war against the Celts. But this written record must be interpreted very carefully, because much of it was anti-Celtic propaganda meant to justify the destruction of the Celts. Plus, many of those historians never set foot outside of Greece or Rome or even met a Celt. They just repeated what others had written. The second source is archeology.

Anyone who is seriously interested in the Celts must include a disclaimer, so I include it here. I am not interested in the neo-Druids, the people who put on white robes and show up at Stonehenge at the equinoxes. There is a vast body of romantic, imaginative and speculative material about the Celts and the Druids. We must ignore all that. And by the way, Stonehenge is not even Celtic. Stonehenge is thousands of years older than Celtic civilization. Celtic civilization was contemporary with classical Greece and Rome.

Graham Robb’s book is one of the most important new books about the Celts to come out in years. It is meticulously researched, with something like 500 sources cited in the notes. Robb’s focus is on Celtic astronomy and geometry, and how those things affected the physical layout of the Celtic highway system and Celtic towns. But along the way, Robb’s story touches on many other areas of Celtic life and Celtic culture.

Were the Celts primitive compared with the Romans? Ha! In many ways, Celtic technology and Celtic science were superior. The Celts already had a well maintained system of roads and bridges, which is one reason the Roman armies could move so fast and why it was so easy for the Romans to lay down Roman roads on top of existing Celtic roadways. The Celtic wheeled vehicles were so technically superior to the Roman vehicles that virtually every word for wheeled vehicles in Latin comes from the Celtic language. The Celts’ communications system was faster than the Romans’. The Celts could transmit news from one end of Gaul to the other in a matter of hours, using a network of acoustically well-placed shouters, with protocols for ensuring accuracy. The Romans used runners, which was slower. Robb makes it clear that the Druids were scientists as well as politicians, religious leaders, and diplomats. Celtic society, says Robb, was an intellocracy. It was governed by people who were selected for their merit and who spent as much as twenty years in training.

Why would the Romans (including the Roman church) have gone to so much trouble to completely wipe out the Celtic civilization? The answer, I think, is clear. It was because the Celtic way of life, the Celtic way of thinking, and the Celtic religion were deadly dangerous to the Romans. The Roman culture and the Roman religion simply could not have survived unless Celtic civilization was destroyed. If the Romans had not destroyed the Celts, those of us of European descent would be very different people today.

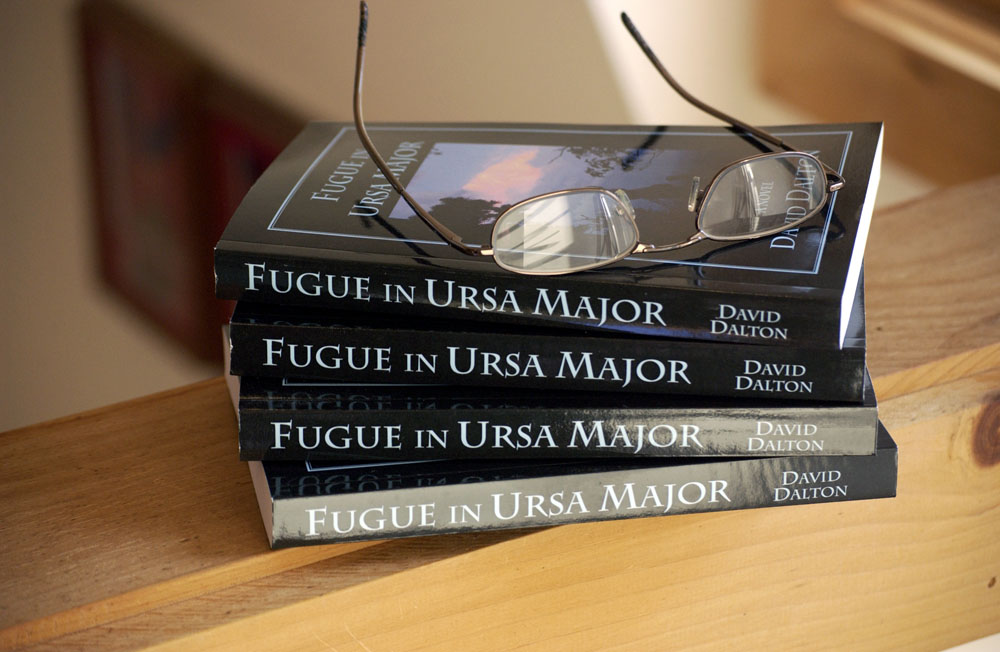

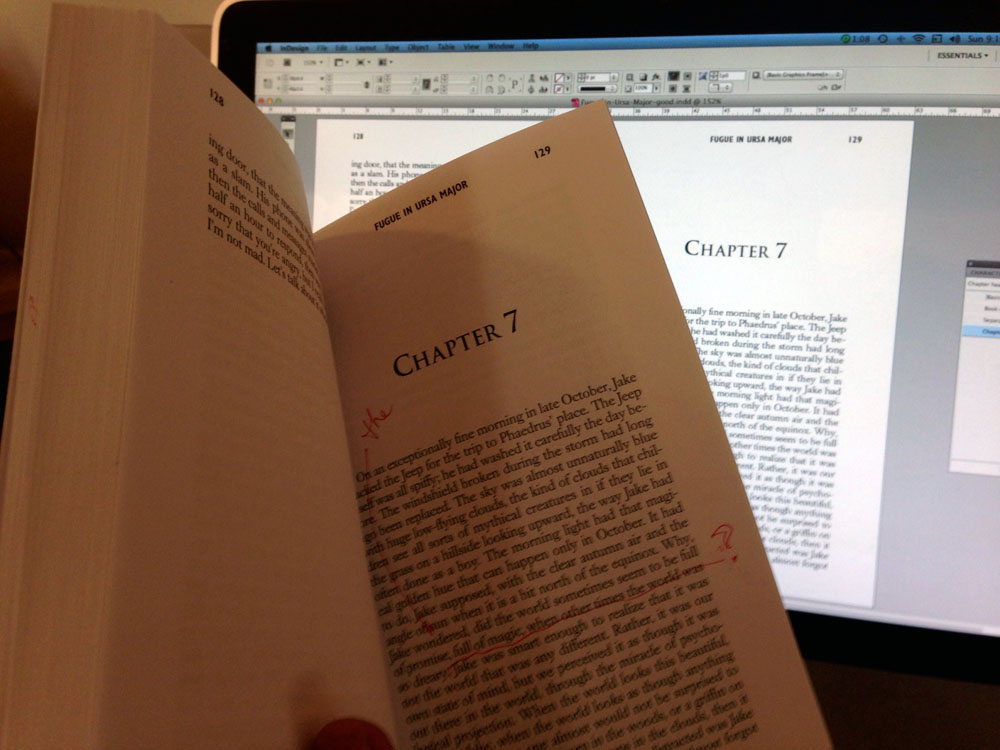

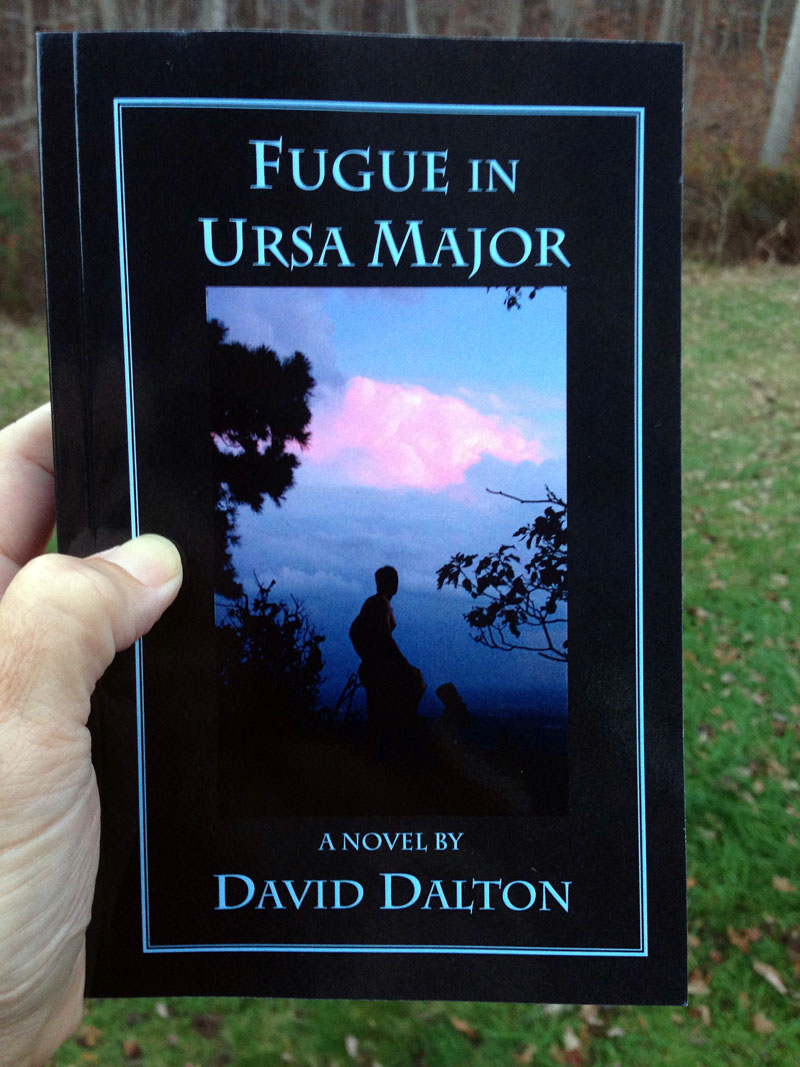

The abiding ugliness of Roman culture and the Roman religion is an important theme in my novel Fugue in Ursa Major. I’ve had to do a great deal of reading about Rome, and the Celts, to make sure that what I’ve written is historically defensible. Graham Robb’s book, though it was published while Fugue in Ursa Major was undergoing its final editing, was a godsend, not least because it gave me greater confidence that I was on the right track.

So, today, as heirs to the cultural poverty and systems of hierarchy and power bequeathed to us by the Romans, is there anything we can do to retrieve what was destroyed when the Celts were destroyed? There may be. The first step: read. But be sure that what you read is from serious historians. Then, when you have a good foundation in Celtic history, use your imagination. How might your life be better if Celtic, rather than Roman, ways of thinking had prevailed?