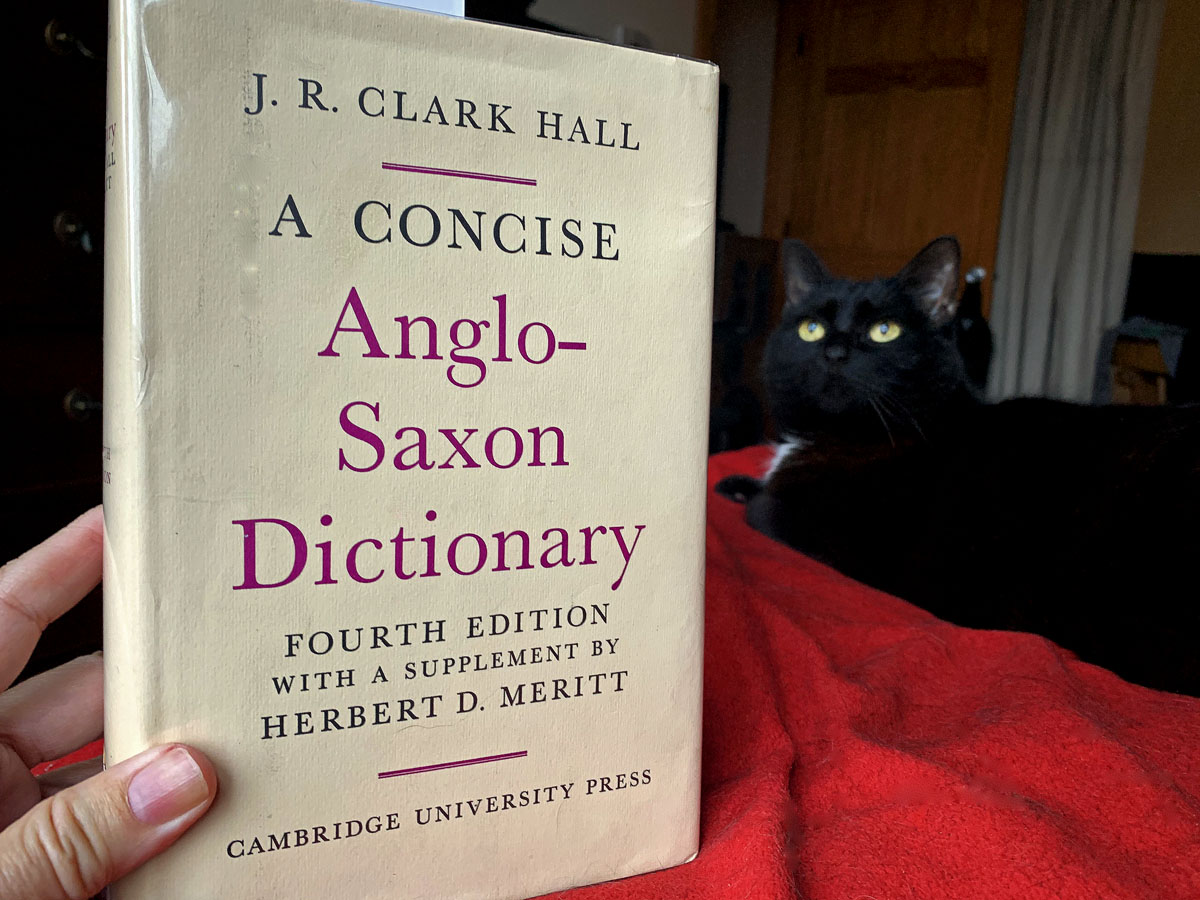

With Lily. We escape together.

Among the teetering stacks of books by my bed, I always keep some books for what I call fill-in reading. This is light reading for short reading sessions — for example, when I know that I’m going to fall asleep after only a page or two.

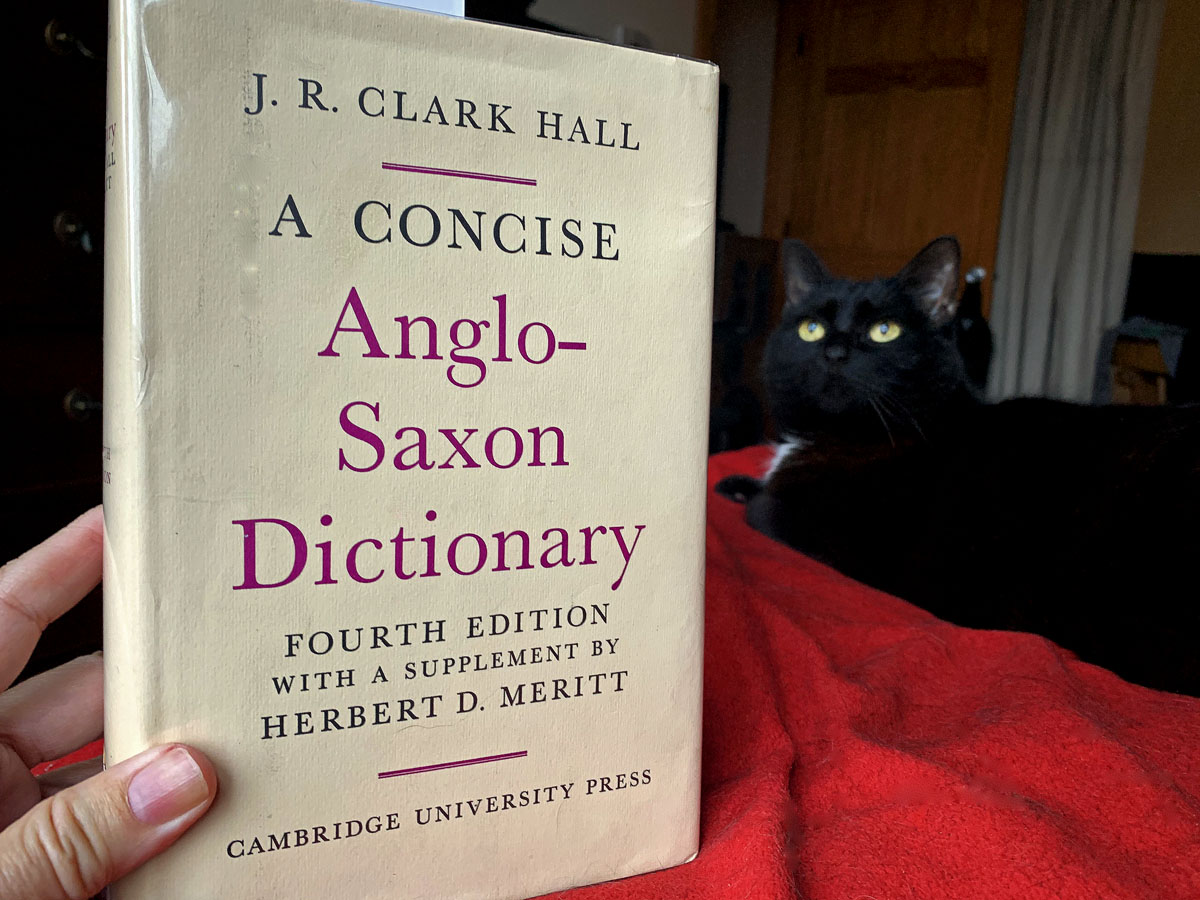

One such book is a 1950s textbook on astronomy, which I’ve been studying for years. Another, for many months now, is A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. The first edition of this book was published in 1894. It has been through several revisions and new printings. My copy is from 1970. Later editions include a supplement, not because new words are being invented in Anglo-Saxon (that’s supposed to be funny), but because the scholarship continues.

Why read dictionaries, or, at least, historical dictionaries? One reads these dictionaries to get a feel for the kind of words a language had. And because Anglo-Saxon (also called Old English) is an early form of my native language, and because I have a good bit of exposure to Latin through Spanish and French, a better grasp of the Anglo-Saxon vocabulary helps provide a better feel for how Old English and French came together after the Norman Conquest to give birth to modern English.

As an editor, I have argued for many years that writers need to know the difference between the Anglo-Saxon components of English and the Latin components. This is because, when we write in Anglo-Saxon, the writing is clearer and is much more useful for persuasion and evoking an emotional response. For telling stories, only Anglo-Saxon English will do. We resort to Latin only when we’re obliged to get technical or abstract. Still, Anglo-Saxon, like German, is rich with a vocabulary of abstraction and objects of the imagination, for example, gēosceaftgāst — a doomed spirit, a word which is found in Beowulf.

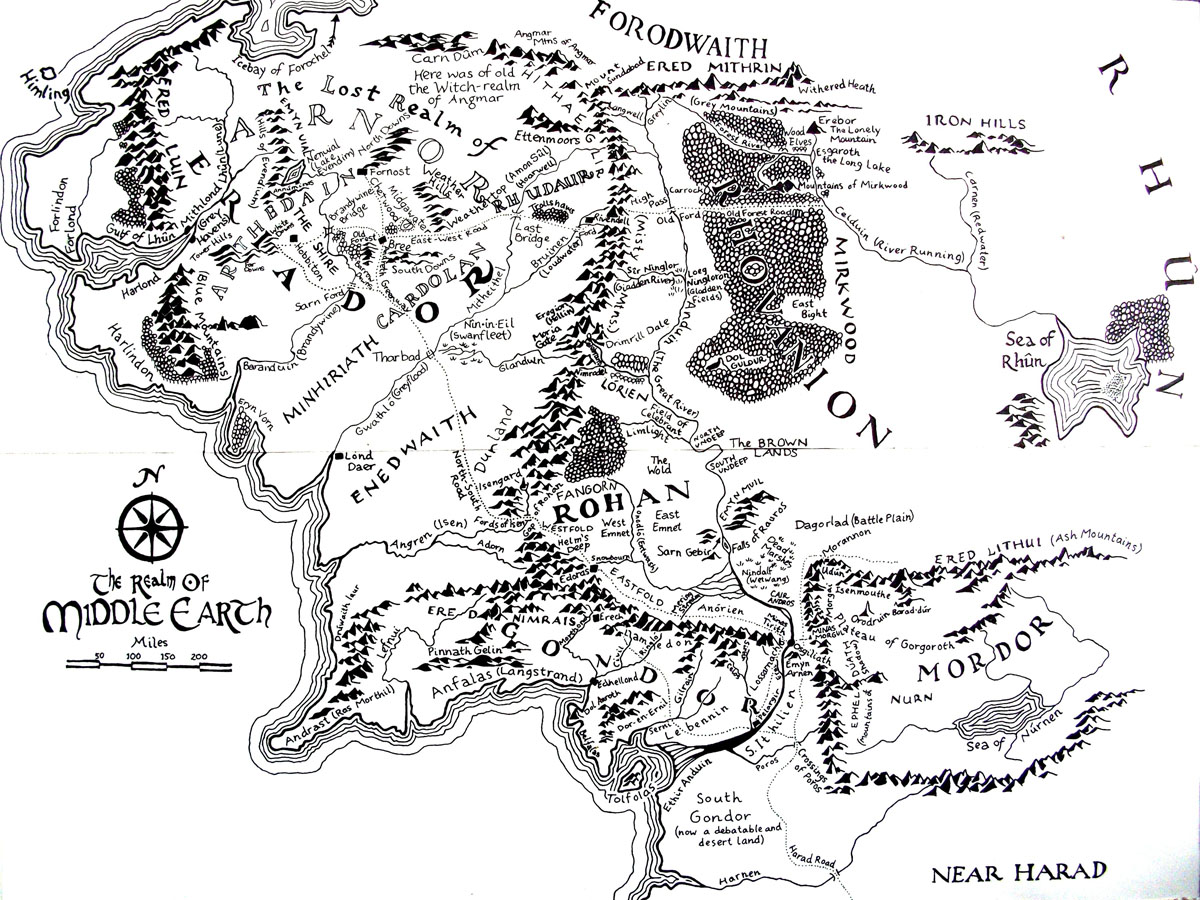

It’s almost impossible now to think of Anglo-Saxon without also thinking of J.R.R. Tolkien, who not only wrote a few of the most famous novels in the English language but who also aroused our curiosity about the roots of the English language.

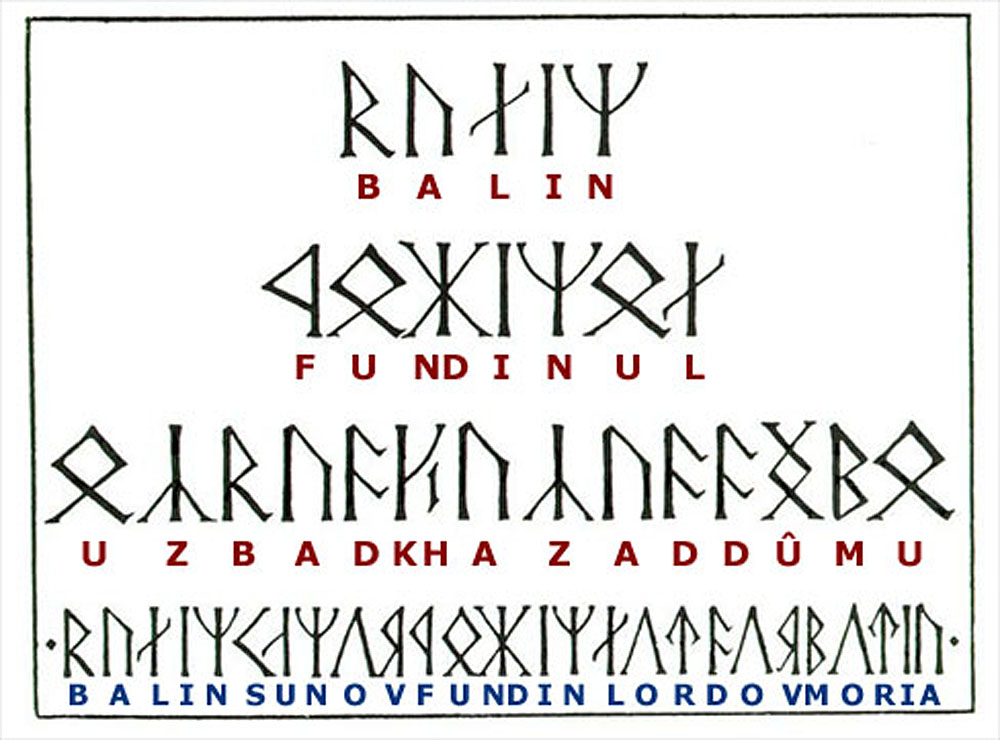

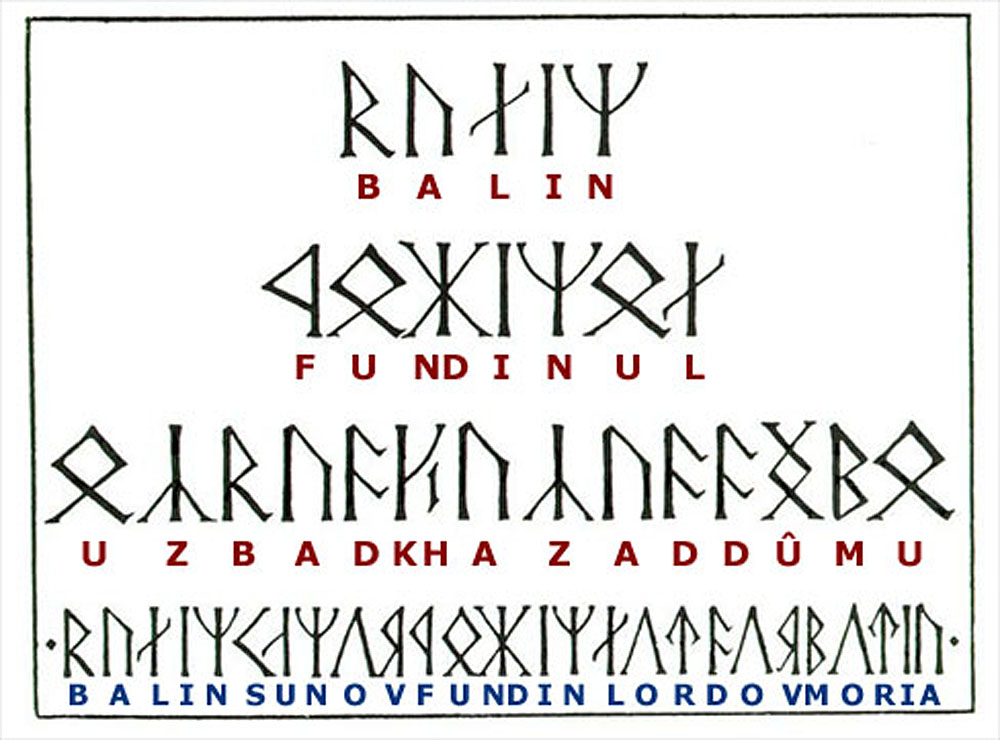

Do you recall when you first saw the runes in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings? The runes then seemed very magical and obscure. Tolkien’s runes are part of a language he invented. But real runes are not so obscure, because they’re an alphabet used for Germanic languages before the Latin alphabet was used. It’s almost a letdown to learn that runes are so well-supported today that they are included in the Unicode table of international characters, which means that most computers can reproduce runes. (If you see question marks in the headline on this post, rather than runes, then your computer must not be fully Unicode compliant.)

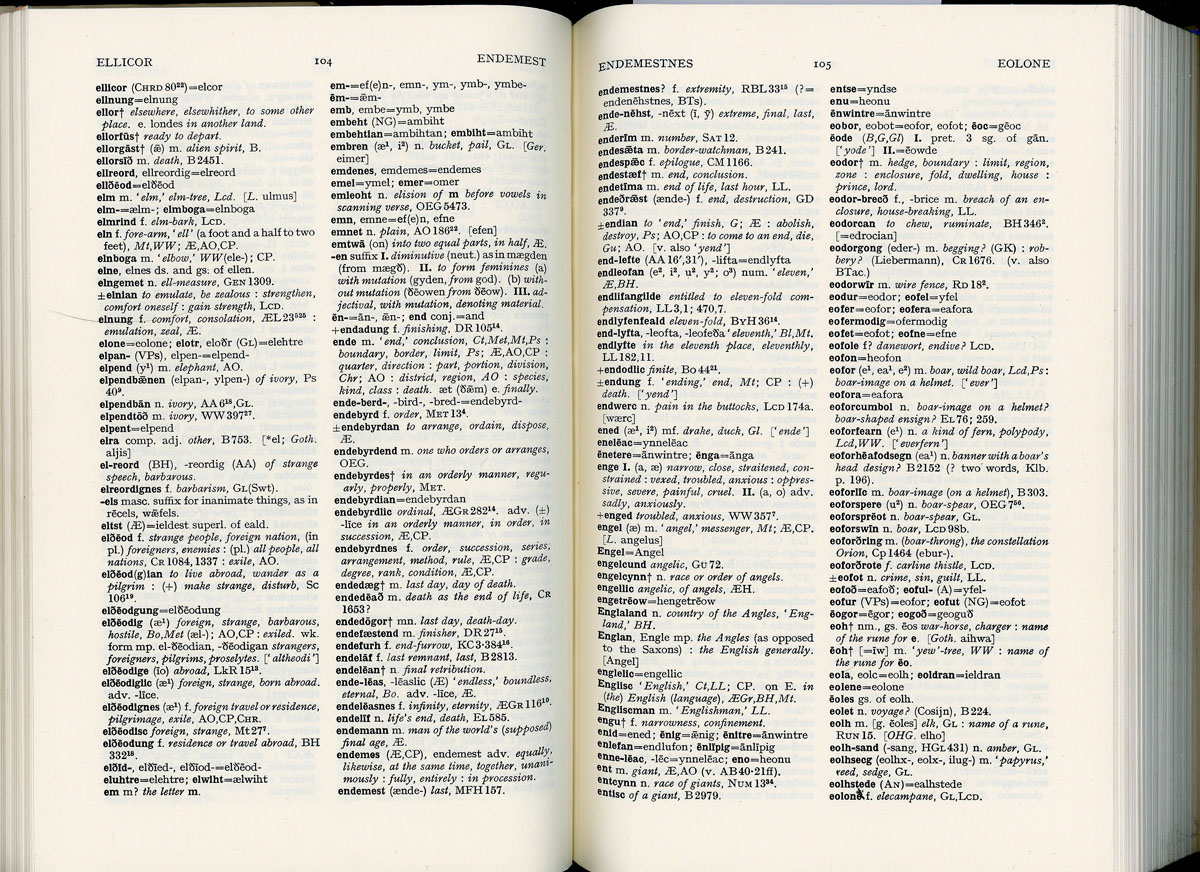

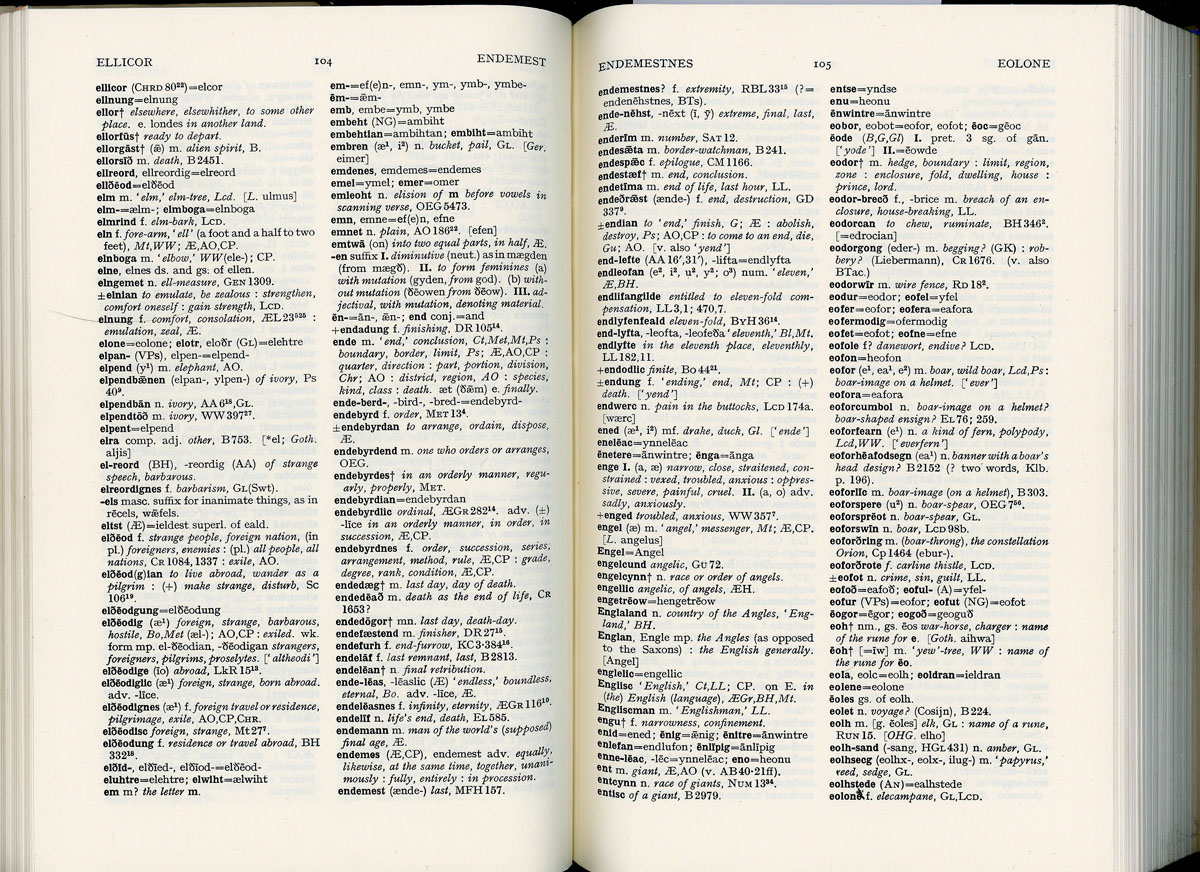

While reading through the Anglo-Saxon dictionary, I found a number of words that I recognize from Tolkien. The page below, Page 105, contains the word ent, for example. It means giant.

The words you’ll find in the Anglo-Saxon dictionary fit roughly into three categories: words that are very familiar and common in English (stēam, for steam or moisture), words that are easily recognizable with a little thought (fordrīfan to drive, sweep away or drive on), and words that are interesting but that make no sense at all (dwæsian, to become stupid).

Our knowledge of Anglo-Saxon is based on about 400 surviving manuscripts. Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries took a heavy toll, though it cleansed England of catholicism. The monks’ revenge, though, is that much of what survives was written down and preserved by monks. Consequently there are a lot of ecclesiastical words in an Anglo-Saxon dictionary. If you subtract the ecclesiastical words, then you have a language that is perfectly suited for describing Tolkien’s Shire, or for telling the kind of stories that Tolkien told. It’s a world of fairy tales and adventure and unspoiled landscapes, a world of people, their surroundings, their thoughts, and their deeds. There’s even the stars. See eoforðring on Page 105. It refers to the constellation Orion. (The ð character is the letter eth and is pronounced like the “th” in “that.”)

It’s a great luxury to be retired and to have time for such pursuits as pursuing the history of the English language. Can you imagine how much fun it might be to do that for a living? Of all the lives that have been lived, I think I most envy the life of Tolkien. I could do without the World War I parts. But I greatly envy his life at Oxford. I can’t find any good photos of Tolkien that don’t require royalties, but here’s a link to some good ones at Getty Images, in which it’s clear that his natural habitat was sitting in a library, reading, wearing his tweeds, and smoking his pipe. The pubs! The Inklings! The books! The walks! The Oxford dinners! It’s all such a wonderful place to escape to in the imagination, and it’s all much easier for me to imagine after a visit to Oxford last summer.

As for escaping, I’m not ignoring the state of the world, or the state of the United States, or the exasperation of reading the news. In fact, I’ve had a lot of little local political responsibilities to deal with of late, such as precinct meetings and fundraising. It’s all a bunch of endwerc †, which you’ll find on Page 105. But that’s all the more reason to have a slosh of ale, or a cup of tea, and to spend a little quiet time trying to think like an Anglo-Saxon.

† Note: The source for the word endwerc is Leechdoms, Wortcunnings, and Starcraft of Early England, which looks like a book I need to read. The book is important enough that Cambridge University Press released a facsimile version, in a three-volume set, in 2012. It’s 1,496 pages.

Click here for high-resolution version

Some of Tolkien’s runes, with translations