Persimmon pudding and cognac. Click here for high-resolution version.

I had persimmon pudding today for the first time in at least 50 years. If you’ve ever once had persimmon pudding, you’ll never forget it, because there’s nothing else like it. I have my own persimmon trees now at last, so I have done my best to reproduce my mother’s and grandmother’s persimmon pudding, using an authentic old recipe from North Carolina’s Yadkin Valley.

Want to try making some persimmon pudding?

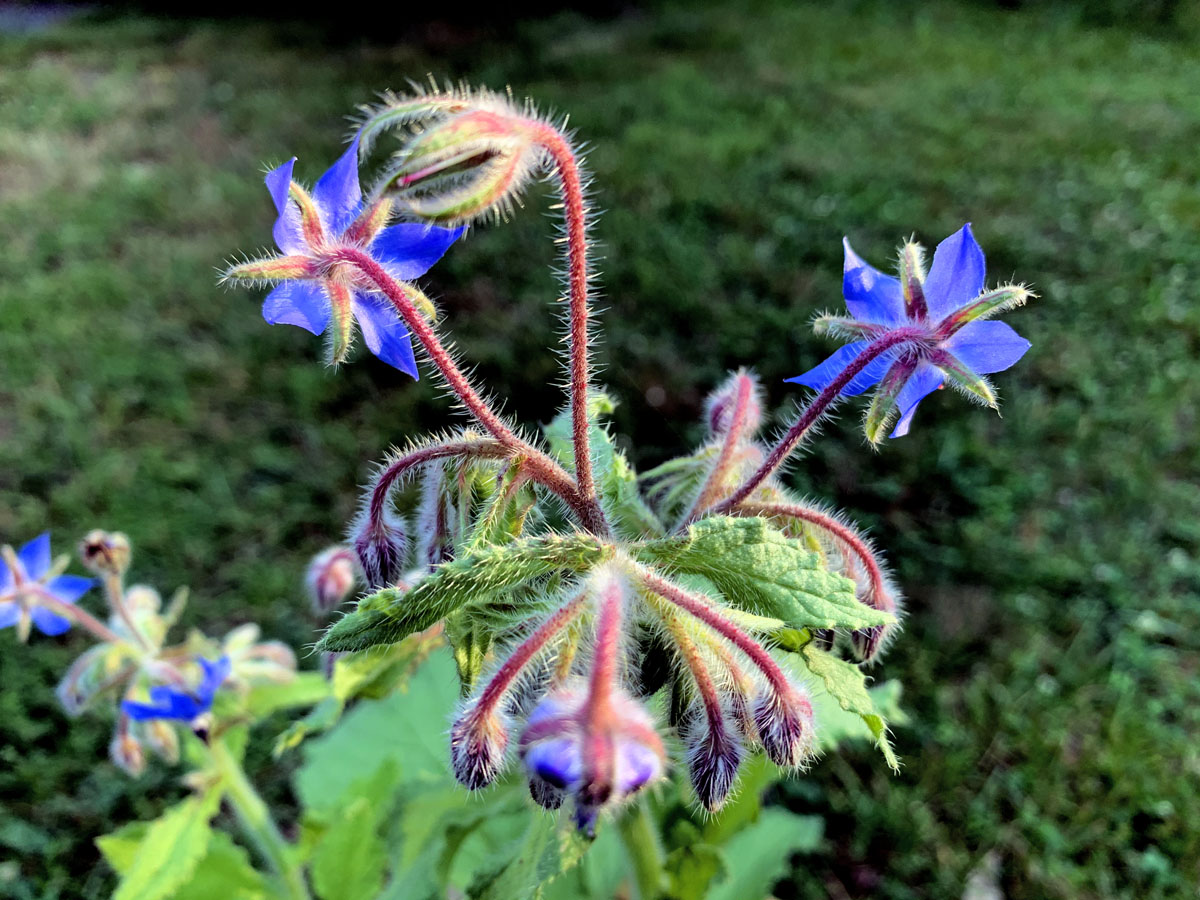

First of all, this post is about Diospyros virginiana. There are many varieties of persimmons in the world. This persimmon is native to the eastern United States. The persimmon tree is very common in the North Carolina Piedmont, where I grew up, and here in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, where I live now. It is most likely to be found on the edges of a stand of woods, where it can get enough sunlight. You won’t find it in woodland interiors. When I lived in California, I often saw Asian persimmons, which are the size of apples, in grocery stores. They clearly are commercially cultivated like apples. However, Diospyros virginiana is a much smaller persimmon. It is a wild tree, but it will happily grow in your yard. One of the photos below includes a couple of coins to show the size of the persimmons.

How I got my persimmon trees: When I bought land here in Stokes County, all of it was wooded. I cleared an acre for a house, yard, garden, and orchard, leaving a few high-value trees standing. That was in 2009. Though I planted a good many trees, such as a bunch of arbor vitaes, many trees volunteered. I let the volunteer trees grow where they suited the landscape. Persimmon trees volunteered very quickly. The wildlife eat the fruit and poop the seeds. I have about ten persimmon trees in the yard now. I started getting the first persimmons in year five or so, but never enough for pudding. This year, for the first time, I had enough to make pudding. Ideally, you want your persimmon trees where you can mow under them, so that you don’t have to go into a thicket looking for persimmons. Maybe they can be transplanted. I don’t really know, since I didn’t have to transplant.

How to harvest persimmons: My recollection from my childhood is that my grandmother just went out and gathered persimmons off the ground from under the tree. Her trees were older and bigger, though, and I think her best persimmon trees grew in the yard. That, however, won’t work for me here. If I waited for the persimmons to fall, they’d vanish overnight, because the wildlife love them — deer, opossums, and raccoons. For today’s pudding, I had no choice but to pick persimmons off the tree as they were starting to ripen. Then I finished ripening them indoors.

How to tell when persimmons are ripe: There is a myth that persimmons don’t ripen until the frost bites them. That is not the case (though frost won’t hurt them, if they last that long). If I waited for frost, I wouldn’t get any persimmons, because the fruit would fall before frost arrives (mid to late October), and the wildlife would get them all. People who aren’t from around here sometimes think that persimmons are poison. That’s probably because they tasted a green one and learned how awful it tasted. There is nothing more astrigent than a green persimmon. It’s not possible to emphasize this too much: Your persimmons must be ripe. When they ripen, they get soft, so soft that they fall off the tree. You can’t possibly cook with persimmons that are not ripe. Not only would unripe persimmons not be soft enough to pulp, they’d also taste terrible. Can they be too ripe? Probably not, as long as they’re not starting to rot. Actually, they’d probably ferment before they rot. You want them right before the point at which they start to ferment.

How to ripen them if you picked them off the tree: If you pick your persimmons off the tree, don’t pick them until they are starting to ripen and are starting to brown. (See the photos below for typical colors.) If you pick a green persimmon, it would never ripen. Bring your persimmons indoors and spread them out on a baking sheet. Cover them with a dish towel or some muslin to keep the fruit flies off. They won’t ripen all at once. Each day, pick out the ones that are ripened and soft and move them to the refrigerator to wait for the others to ripen. It took a week for all mine to ripen. By this time, they also had started drying out some, which I was afraid might be a problem. It was hard work, but they pulped just fine. One of the photos below shows what the ripe persimmons should look like. Notice that all the ripe persimmons are pretty much the same golden brown color.

How to pulp your persimmons: You must use a food mill. You can find them on Amazon. The food mill will mash the persimmons and press out the pulp. If your food mill comes with different size strainers, use the fine one. You don’t want any bits of seeds or skin to get into your pulp. One of the photos below shows what the finished pulp should look like.

How to make pudding: No doubt there are other things that can be done with persimmons. In the rural culture in which I grew up, though, pudding was what persimmons were always used for. If you’ve never had persimmon pudding, that’s a bit of a handicap in trying to make it, because you don’t know what the goal is. But there are several things to keep in mind. First, it’s pudding, not cake. After it has finished baking, it will be dense and heavy and a bit squishy. After it starts to cool, the pudding will weep a dark syrup. That’s exactly what you want. In the recipe below, 2 cups of sugar sounds like a lot. Yet I think it’s necessary for a proper pudding. The crust of the pudding should caramelize, and the caramelization is an important part of the taste of the pudding. Some people may bake the pudding in a single, fairly deep vessel. However, in my opinion the only proper way to do it (that’s how my mother and grandmother did it) is to bake the pudding in three iron skillets of different sizes. (See the photo below.) This increases the amount of crusting and caramelization. And the cast iron, as long as it’s well seasoned, will give the pudding the kind of crust you want. Don’t be misled by the word “crust,” though. The crust is soft and is part of the pudding.

About this recipe: As far as I could determine through family sources, my mother and grandmother did not use a recipe. They “just stirred it up.” However, with the help of my sister, a cousin provided a traditional recipe from the Yadkin Valley that is just like my grandmother’s pudding. The recipe came from the 1988-1989 cookbook of Society Baptist Church in Harmony, North Carolina. I believe the church lady who provided the recipe was Nancy C. Koontz, who I hope won’t mind, if she is still living, if I reproduce the recipe here.

Yadkin Valley persimmon pudding

2 cups persimmon pulp

2 cups sugar

2 cups flour

1 teaspoon baking powder

2 eggs

2 cups milk

1 teaspoon vanilla

1 teaspoon cinnamon

3 tablespoons melted butter

Bake at 350 degrees.

How to mix the batter: The recipe assumes that the cook has the experience to know how to mix a batter, and no instructions are provided. I’d suggest mixing the egg, sugar, cinnamon, vanilla, and melted butter in bowl 1. In bowl 2, mix together the milk and the persimmon pulp. Add the contents of bowl 1 to bowl 2. Then add the flour, a cup at a time (plus the baking powder) to the mixture. I used a mixer for the final mixing to avoid lumps in the flour.

How to tell when the pudding is done: This is important and requires some skill and experience. Your pudding won’t be edible if it’s underdone. If it’s overdone, it will dry out and the crust will get too dark or blacken. How long you bake it will depend on the kind of pan or pans you use. Use the toothpick test! Even though the finished pudding is soft, the toothpick test will work and the toothpick will come out clean when the pudding is done. With the batter in three iron skillets, my pudding took about 30 minutes. My cousin bakes the pudding in a single a single 9 x 13 baking dish and gives it an hour. But watch the pudding, not the clock!

This was a lot of work, wasn’t it? But you only get persimmons once a year.

Click here for high-resolution version.

Notice the range of colors. These persimmons are not yet ripe!